A New, Desensitized America

by Kasey Mathews | published Dec. 11th, 2019

Wow, that’s absolutely terrible. Sending my thoughts and prayers. Wishing that community a quick recovery. I couldn’t imagine such a thing. We’re a nation rocked with grief. This will surely serve as a wake-up call. Change is needed. And now for the weather.

Tragedy has become so commonplace in our daily routine that it, too, has become as quintessentially American as apple pie and baseball. Every day, horrible news comes across our screens. Yet, more often than not, we treat these bulletins as an annoyance — a momentary interruption to our regularly scheduled programming.

"Every day, horrible news comes across our screens. Yet, more often than not, we treat these bulletins as an annoyance."

There were 340 mass shootings in 2018, accounting for 373 deaths and 1,346 injuries, according to Business Insider. Escalating this statistic, CBS reported in September 2019 that there had been, up to that point, more mass shootings in America than days passed in the year. This is the first time such a high number of mass shootings has ever been recorded. The first time, that is, since 2016.

A mass shooting, as defined by these numbers, is any shooting in which four or more people are killed within a localized time and location, not including the killer.

With so much tragedy and loss bombarding our everyday lives, why are these events not being taken as seriously as events in the past?

Framing the Past

In 1999, the high school in Columbine, Colo. was ravaged with violence as two gunmen — students of the school — stormed the building and opened fire upon their classmates.

As Reporter senior writer Leland Goodrich discussed in the article “Is Arming Educators the Future?”, the news shocked the nation. People from Connecticut to California mourned alongside the heartbroken community. Media covered the story for months, with updates given every day.

It was a lot, and for good reason.

As Joe Berkowitz of Fast Company explained it in his article, “some of the nonstop coverage may have been driven by if-it-bleeds-it-leads sensationalism, but something else was at play: a struggle within the nation’s very soul.”

Such an event was completely unthinkable at the time — so many innocent fatalities; so many more injuries. Even now, as mass shootings occur, they are so often harkened back to Columbine, as it serves as a vital touchpoint in the American conscience.

School shootings had happened before, even within just the past year. So Columbine wasn’t the first. But the scale was unprecedented — two gunmen killed 12 of their fellow students and one teacher.

Adapting the Present

Now, Columbine isn’t even listed among the 10 deadliest shootings in modern U.S. history and hasn’t been since November 2017.

The Washington Post took a look at various points in the timeline of recent mass shootings, utilizing two notable events as signposts to divide this timeline. Through this division, we are able to see the exponential growth of shooting frequencies. The Columbine High School massacre occurred on April 20, 1999. On June 17, 2015, nine people were killed at a Bible study in a historic African American church in Charleston, S.C.

Before 1999, mass shootings took place on average every six months. Between April 1999 and June 2015, the average was shortened to once every two-and-a-half months. In the time between the Charleston shooting and August 2019, this shortened to an alarming one every six weeks.

Looking at the sheer volume of mass shootings, one can see trends emerge. Most shooters are men, who have been getting progressively younger. A heart-wrenching number of victims were children and teenagers. The frequency is now unthinkable. And yet, how much of that matters when these events are tuned out and relegated to our periphery?

We experience more mass shootings now than ever before. Admittedly, many often look to compare the number of these shootings in the U.S. to those around the world. Yet, the data behind these numbers is foggy at best, leaving these comparisons difficult to assign merit. It is inarguable, however, that the rate of domestic shootings has dramatically increased in recent years. Shootings, however, aren't the only type of tragedy to befall this nation.

Effects of Tragedy

In November 2018, a wildfire raged across California. It tore through a number of towns, destroying much and terrifying many. The Camp Fire, as it came to be known, was the deadliest, most destructive fire in California's history.

As it burned, towns and cities such as Paradise were engulfed in flame.

“For thousands of residents, the terror of sitting in traffic jams as the wildfire bore down left emotional scars,” said Stephanie O’Neill in an article titled “Mourning Paradise: Collective Trauma In A Town Destroyed.”

Eighty-five were killed in the area, with thousands more left homeless. It took some residents hours to escape the city, as day turned to night and explosions could be heard all around — the sound of superheated residential propane tanks overwhelmed by flame.

Whereas nightmares and flashbacks are normal in the immediate wake of a disaster, according to Executive Director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory University School of Medicine Barbara Rothbaum in O'Neill's article, it becomes worrying when these symptoms persist for longer than a month. She observed this in analyzing the effects of the Camp Fire in Paradise.

“It’s very similar to the grief process,” Rothbaum was further quoted as saying. “We don’t think there’s any way to the other side of the pain except through it.”

Avoiding this pain can lead to long-term trauma. Those who do not acknowledge their pain — by talking about the experience, journaling it or some other method of healthy coping — can experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This can affect one’s life long term, inhibiting the individual from continuing on as they did before the trauma.

"The community is traumatized, and we are all members of that community."

Revisiting Columbine, the tragedy held an impact that was widespread and long-lasting. Typically, those who experience a traumatic event firsthand are who we associate with being traumatized. However, as the Los Angeles Times reported on April 23, 1999 — just three days after the massacre — it wasn’t just the victims experiencing this trauma. The article was titled “Frenzy, Shock, Numbness Have Faded; Now Comes the Pain.”

“Emergency workers and SWAT team members who first ventured into the high school’s blood-soaked library are starting to seek grief therapy,” reported Julie Cart, author of the Los Angeles Times article. “The therapists, in turn, are themselves getting help.”

Cart later reported that even those who debriefed the therapists and helped them sort through their emotional overload often sought debriefing, themselves.

The community of Columbine reeled from the massacre, including those who may not have been directly affected. The direct victims may have been the students, teachers and other faculty, but the trauma was felt by the community as a whole — much like those in Paradise, Calif., they were experiencing a collective trauma.

Our Collective Trauma

Gilad Hirschberger, professor of psychology at IDC Herzliya in Israel, explained collective trauma as “a cataclysmic event that shatters the basic fabric of society.”

As seen at many other sites of tragedy, communities tend to grieve as one, and the effects of a tragedy are recognizable long after the event itself has passed.

But where do we draw the lines of “community”? The increasingly high amount of mass shootings, among other horrific events both natural and manmade, take their toll on the American psyche. Due to the large number of these terrible blights, many Americans have begun to feel the effects that one might expect from those more directly tied to tragedy.

One event may dramatically affect those it impacts directly; however, we've been experiencing a larger number of events at a higher frequency. Due to the increased regularity of these events, the perceptions of safety and security held by those much more distant from the individual epicenters of these tragedies have been impacted, too. Now, we’re all feeling the shared effects of these events.

The community is traumatized, and we are all members of that community.

So is our tendency to no longer dwell on singular events due to the sheer volume of these events? Is it an involuntary defense mechanism to protect ourselves from further trauma? Or is it simply the tendency toward a more rapid news cycle? Regardless, it’s not healthy.

Anticipating the Future

While measures have been put into place in a number of areas attempting to prevent further tragedies — mass shootings, natural disasters or otherwise — the grim reality is that these attempts are likely not going to succeed overnight.

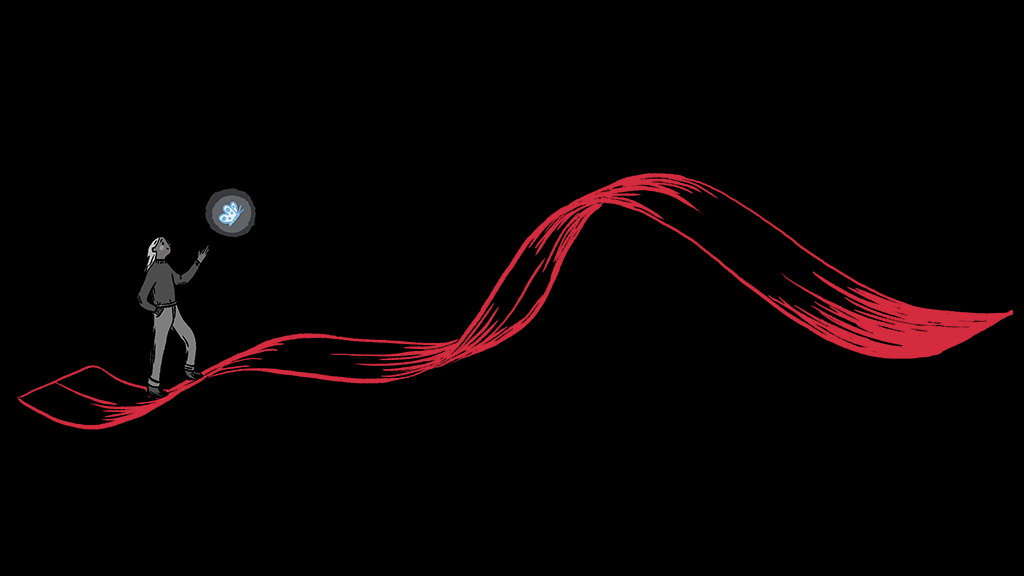

We’ll be continuing onward as a nation, trudging through this horrific emotional wasteland for at least a while longer. How can we ensure we come out the other side with our psyches intact? Our current method has been to desensitize ourselves, but is that the best method?

As Rothbaum said, it’s important to work through trauma rather than ignore its effects. We cannot tune out a nation wrought with disaster. We must acknowledge it. Discuss it. Learn from it.

According to Dr. Sandro Galea, dean of Boston University’s School of Public Health, there are two key methods for a community to recover from collective trauma.

The first is to seek regular mental health treatment. Cognitive behavior therapy is one such approach that Galea recommended. Broadly speaking, this entails a course-correction of negative or unhelpful behaviors, such as attitudes, thoughts or beliefs. These are nudged to be more positive, helpful and emotionally regulated, leading to a healthier thought process and therefore a healthier mental state.

The second is to address the operation of the community on an economic and social scale. While America is operating economically, the social level is questionable. Should we continue to ignore these issues rather than take note of them, we fail to operate socially.

The more we swipe away notifications of terrible tragedies, the more we willfully ignore the implications of another mass shooting or infrastructural failure, the more we fall into the spiral of trauma.

"The more we swipe away notifications of terrible tragedies, the more we fall into the spiral of trauma."

Outrage can be annoying. It can demand much of our energy. Worse, it can lead people to think about topics easier left ignored. But it acknowledges and addresses issues in a way that connects people and progresses through the darkness.

The longer we sit and ignore the looming danger around us, the less likely we are to come out the other side unscathed. To achieve a better future, we must be attuned to the present.

Flipping through the pages, we look at issues through the lens of an outsider. We fail to realize, willingly or otherwise, the real impacts these topics have on our lives and our mental state. We can either continue to pass and distract ourselves with other things and inevitably continue on our path of desensitization; or we can address the issues plaguing our communities.

America touts itself to be the epitome of success and defender of the Free World. Yet its citizens are readily prepared to ignore those issues and divisions that threaten to tear our society apart. We're too entranced by simple distractions to recognize the flames around us. By the time we feel them licking at our heels, it may be too late.