Silicon Valley and the Data Empire

by Tommy Delp | published Jun. 25th, 2020

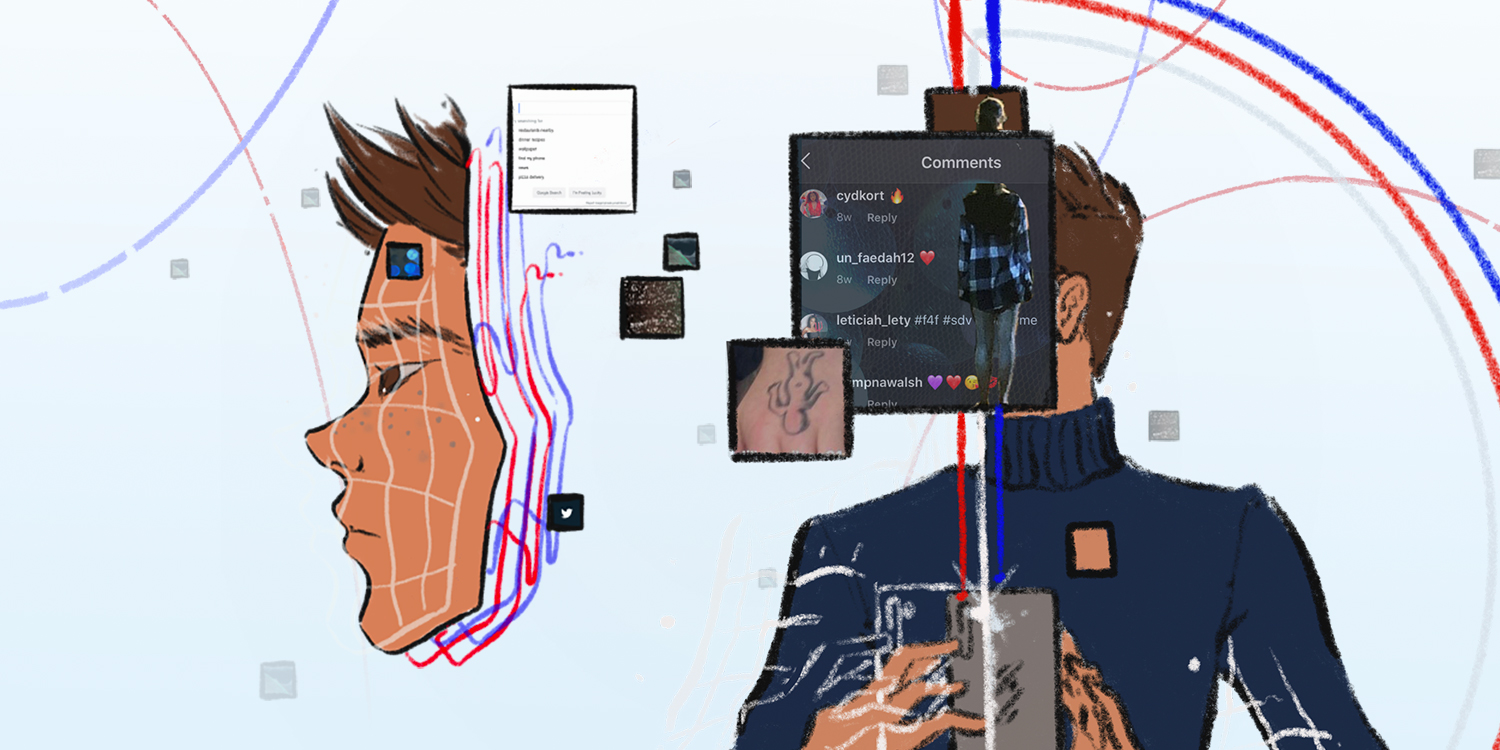

Data privacy. Many call for it, but no one truly has it. Whether it be Facebook, Google or another one of the Silicon Valley behemoths, the amount of data collection going on in today’s modern connected world is immense.

For the individuals who truly want to protect their online privacy, it’s an uphill battle. The non-material idea of data makes for some rather messy legalities.

“The idea of data is legally constructed, and it varies by place. There’s not one definition,” said Kaitlin Stack Whitney, assistant professor in the Science, Technology, and Society department of the College of Liberal Arts.

Society may be moving further into the future every day. Due to a lack of understanding and conformity though, our laws are rarely as forward-thinking — especially when it comes to technology.

What’s being done with consumer data though, and how truly invasive is its collection? More importantly, is there anything we can do as individuals to stop it from happening?

How Big Can Data Get?

Companies want consumer data for a clear reason. Everyone’s data, including your own, has economic value.

Consumers often don’t take into account that it costs companies money to run services such as Facebook and Google. Your data is often the price you pay to access these 'free' services.

Ben Woelk, program manager at RIT’s Information Security Office, stated, “Essentially, there’s a cost for everything. And for us to be able to use these products, there is a cost in terms of the data we’re willing to share.”

“There is a cost in terms of the data we’re willing to share.”

This isn’t to say that everyone could simultaneously stop giving their data away and start cashing it in for big paydays.

Stack Whitney clarified, stating, “Companies aren’t interested in amassing data one person at a time. The value is in the aggregate.”

What do they do with this vast amount of data though?

Not at all surprisingly, they use it to make more money. They do so mostly through targeted advertising.

Tech companies sell personal information, whether it be age, race, hobbies or gender, to marketing companies who use it to build buyer profiles.

“A lot of marketing is built around personas. How do I market products toward someone? What are their interests?” Woelk explained.

Using consumer data, marketing companies are able to decide what kind of product certain groups may have an interest in. Whether kids, tweens or college students, a company can directly target their products and services toward specific audiences.

Signing It All Away

Most of us have experienced opening a new app or social networking service and being greeted by a long scroll of text. Likewise, most of us have likely skipped over said text and clicked okay. That’s a dangerous move, as there’s much more to that agreement than one would imagine.

By consenting to it, consumers allow whatever company to scoop up their data and do with it as they please. Companies may even say they ‘own’ it; though, the idea of data ownership is up for debate in many scholarly circles.

Consumers may be the ones creating the data, but since companies are the ones putting in the effort to collect and analyze it, they often believe they have more of a right to it. That’s where the signed licensing agreement comes into play.

“In our minds, of course we own our data. If we’ve signed the licensing agreement saying that we’re going to provide it though, we may have given up our rights to it,” Woelk stated.

“We need to ask what information is being given and if people understand it.”

What can consumers do to stop such an invasion of their privacy? Well, for one, they could try to read the agreement.

It’s usually long and complex though, setting them up for failure. Consequently, if a consumer cannot be fully informed on their actions, are they truly able to consent to such a contract? That’s one of Stack Whitney’s problems with the current system.

“It’s not as simple as just giving people information," she said. "We need to ask what information is being given and if people understand it.”

A Fight on All Fronts

There is no perfect solution to the data privacy dilemma. While consumers definitely need to make themselves more informed, it’s hard to believe the fault lies wholly on them.

Tech companies often work together to create standards and regulations. They could use these skills to create a more universal and easily understood agreement framework. The government, if necessary, could also step in. Yet, they are rarely forthcoming with their own use of consumer data.

A government intervention could come in various degrees, ranging from requiring tech companies to simplify their agreements to stopping the more thorough types of collection in the first place.

“When it comes to setting up protection, there are reasons to believe that mandates, at some scale, would be the only way to make companies disclose information. They may not comply otherwise,” Stack Whitney pointed out.

Some states are starting to enact more strict data privacy laws. Often though, through loopholes in the legislation, companies are finding ways to sidestep these new regulations.

Maybe there’s a more holistic solution to increasing data privacy — one that requires some work from all parties involved. Woelk believes in a solution along these lines.

“Explaining things is on the company, enforcing things is on the government, and it’s on the consumer to be knowledgeable about what they’re sharing,” he said.

Simply put, based on the current laws in place, the best solution may be to just be proactive in your data sharing.

Read the licensing agreement even though it’s long and wordy, and think about where you’re sharing your information. Not every website needs to know your hometown and birthday.

Then again, we’re living in an online society. It’s most likely too late to change what are now social norms.

As with most legal squabbles, one group — whether it be the companies or the individuals — will have to succumb. Some worry, though, that it’s Silicon Valley’s game to lose and the people's burden to bear.