A Post-Mortem of Net Neutrality

by Patrick McCullough | published Oct. 4th, 2021

The Biden administration has appointed Jessica Rosenworcel as acting head of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), following the previous chairman’s resignation.

Rosenworcel supported net neutrality legislation during her time as a commissioner for the FCC. Now, the Democrat-controlled FCC appears poised to restore the net neutrality rules that had been stripped out under the Commission’s previous chairman, Ajit Pai.

A Neutral Internet

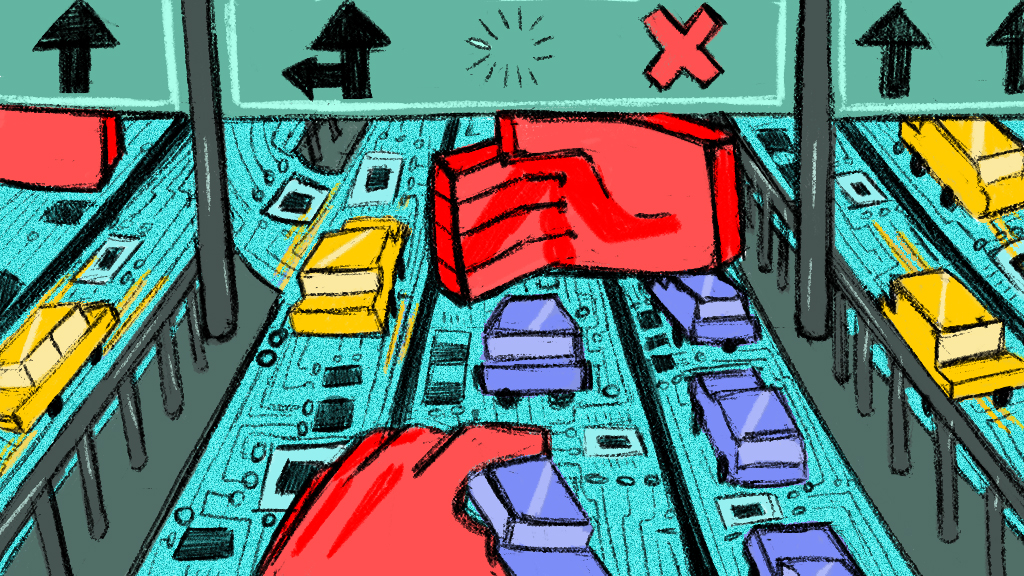

Net neutrality is the concept that all data traveling through a network should be treated equally.

Nate Levesque is an RIT alumni who works on the Datto Networking Team.

According to him, “net neutrality has to do with access. We can’t really connect to the services we use directly."

An internet service provider (ISP) sits between a computer and the rest of the internet. Any traffic over the internet has to pass through one of these companies before reaching its destination.

Levesque elaborated, saying that “the issue at hand is that company, your internet service provider, can see where your traffic is going, ... and manipulate your traffic in such a way that they can encourage you to use something else, or make different decisions about what you’re doing online.”

Net neutrality legislation seeks to keep ISPs from engaging in this sort of manipulation by ensuring that they treat all the information passing through their networks the same.

Advocates, like Levesque, fear that without these protections, ISPs would be able to implement artificial restrictions on their customer’s activities.

“[ISPs] might decide to block a website because the company decides that I shouldn’t see it,” Levesque explained. But there are more subtle ways that ISPs can influence users.

“[ISPs] might decide to block a website because the company decides that I shouldn’t see it.”

"They can manipulate the speed of things a little bit, and it doesn’t take a lot to convince someone to use a different service,” Levesque elaborated.

These fears aren’t baseless. Internet companies have artificially throttled certain websites in the past, and they continue to do so today.

Just this year, the internet service provider, Your T1 WIFI, showed their support for then-President Donald Trump after he was banned from Twitter for inciting violence amongst his followers. The ISP protested the idea of a tech company controlling what its users see by blocking their users from accessing Facebook and Twitter unless they contacted the company to ask for permission.

Legislating the Internet

In 2004, under Chairman Michael Powell, the FCC encouraged ISPs to promote a set of four essential “Internet Freedoms.”

These ideals urged companies to voluntarily uphold the principles of net neutrality. As it stood, the FCC did not have the tools to actually enforce these protections.

Enforcing net neutrality hinges on how ISPs are classified under the Communications Act of 1934. There are seven ‘titles’ laid out in the act, which governs the guidelines different service providers operate under.

Title II providers are considered public utilities, such as gas, telephone service and electricity. Under this classification, the FCC could regulate internet service providers the same way they regulate telecommunications companies - as indiscriminate pipes that treat all online traffic the same.

The Open Internet Order reclassified ISPs as Title II services in 2015. It focused on three specific rules internet companies had to follow: no blocking traffic, no throttling traffic, and no paid prioritization.

In 2017, the transfer of presidential power brought with it a new Republican-appointed FCC chairman, Ajit Pai. Under his direction, the FCC began the controversial process of dismantling the Open Internet Order.

Pai argued that a Title II classification was an unnecessary burden on companies, claiming, “If our rules deter a massive infrastructure investment that we need, eventually we will pay the price in terms of less innovation.”

On the other side of the aisle, Democrat commissioners argued that giving ISPs the ability to block websites and throttle content opened the floodgates for abuse.

Then-commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel stood by the need for net neutrality, “[ISPs] have the technical ability and business incentive to discriminate and manipulate your internet traffic, and now this agency gives them the legal green light to go ahead and do so.”

A Bipartisan Issue

A new proposal for net neutrality legislation is being pushed by the current Democrat administration, but according to Benjamin Banta, a professor at RIT’s Department of Political Science, that doesn’t mean the issue is cleanly split down party lines.

“If you look at the polling on net neutrality there’s a sizable chunk of the Republican party’s voting base that would like to see it still in place. It’s just not very high up on their list of priorities,” Banta explained.

For some people, Pai’s treatment of net neutrality was enough to cause them to break with the party entirely.

“I had a student, I think Ajit Pai’s reversal of net neutrality radicalized him. He was a rock-ribbed Republican, and he came to class one day with his new Democratic party registration,” Banta said. “He now does digital work for local congressional campaigns on the Democratic side.”

“I had a student, I think Ajit Pai’s reversal of net neutrality radicalized him. He was a rock-ribbed Republican, and he came to class one day with his new Democratic party registration.”

According to Banta, the issue isn’t partisan — it’s corporate. Debates like the one over net neutrality are born out of an ecosystem where the interests of organizations with political power don’t align with the interests of the people.

“This case of net neutrality going the way it did, with Ajit Pai ignoring the will of the people and his party figuring, ‘We can get away with this, we can still win elections,’ is largely a function of a political party that is captured by big corporate interests,” Banta explained.

Where We Are

The important thing to take away from the debate over net neutrality is that participation in the conversation is necessary, regardless of a person’s views on the matter.

If people don’t make a decision on it themselves, then somebody else will.