Art World Elitism in the Contemporary Age

by Catherine Rafferty | published Jun. 25th, 2020

The fine art world can be perceived by many as an intimidating sphere of high culture that everyday people are apprehensive to approach. Art in the formal, institutionalized sense can seem both financially and intellectually inaccessible. However, the fine art world is arguably more accessible than it has ever been due to the advent of photography, the internet and modern-day social movements.

What is “fine art” and who gets to decide? How is the contemporary art world reconciling with its classist past?

Commodification of Art

Today, art auctions and fairs are selling works globally at remarkably high prices. Christie’s, a major art auction house in New York City, just last year sold a 1986 sculpture by Jeff Koons for $91.1 million. This set a new record for the most expensive work sold by a living artist. Christie’s is also responsible for the sale of the most expensive work ever sold at auction — “Salvator Mundi,” a recently rediscovered painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, fetching around $450 million.

The art market’s connection to the financial elite is not new. Art and wealth have been in close association since antiquity. Michael Amy, professor of Art History at RIT, explained that the art that filled public museums up until the 1960s was mainly produced for the upper class.

"[Buying art] is something that is reserved for that part of the society that has means that go beyond survival.”

“There's no need for art. One can survive — it would be painful for many of us — but one can survive without art," said Amy. "So, it [buying art] is something that is reserved for that part of the society that has means that go beyond survival.”

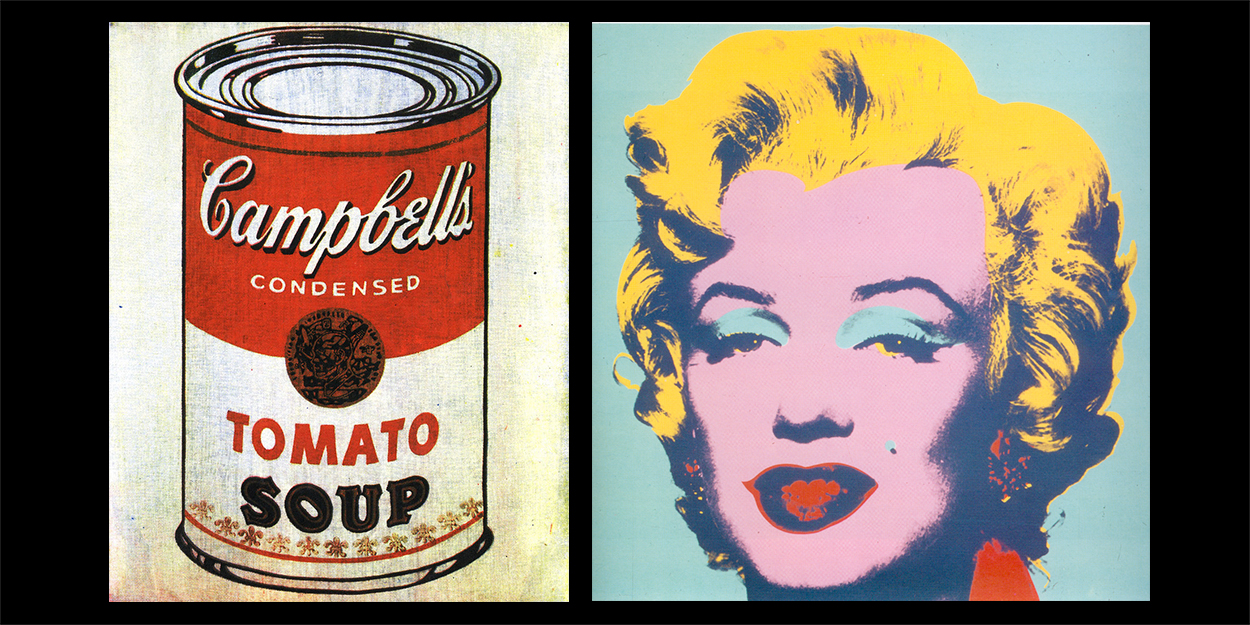

However, in the 1960s, the art world saw a shift in what was considered art and who could produce it through the modernist movement. Around this time, the art market started to operate in the same leagues as luxury brands. In her 2014 book, "Big Bucks: The Explosion of the Art Market in the Twenty-First Century," art market reporter Georgina Adam described how this change translated to the business side of things. The core of the art auction businesses shifted away from Old Masters and Impressionists throughout the 20th century. Major auction houses, like Sotheby’s and Christie’s, recognized that auctioning contemporary art could open up a whole new audience of buyers.

Illusion of Inaccessibility

Now, art is more accessible than ever, but that doesn’t change the fact that people in the lower class often feel excluded from the conversation around high art. The modern and contemporary art movements are highly conceptual forms of art that the public find difficult to consume and understand without a knowledge base to fully appreciate it. And understanding of this art seems dependent upon formal art education, such as a BFA or MFA university program, where you have the opportunity to learn about the history behind the art we see now and be introduced to the people who will get your own work out into the world.

A 2014 study by the artists collective BFAMFAPhD found that 77.6 percent of artists who manage to make a living by selling their work are white, as are 80 percent of all art school graduates. Despite this, there are individuals making gains at a local level who strive for more inclusive art practices.

Who determines what art is and what is considered to be high-value art is all dependent upon the people in power. Art historians’ conventional hierarchy of high art and low art was primarily based upon Western ideologies that excluded many traditional forms of artistic expression.

Folk art, which can be defined as a traditional expression of culture through an object or a performance, is not usually considered when planning shows in standard museums and galleries. Ed Millar, curator of folk art at Castellani Art Museum of Niagara University, is breaking this mold.

“Within the mainstream art world ... they would call folk art basically this ‘naïve art,’" explained Millar. Folk artists are considered "untrained artists that kind of fall outside of major movements like pointillism or whatever."

For many of the folk artists on display, it’s not important to them that they be validated in the eyes of the fine art world. But it is important to recognize that this type of art is just as legitimate as any other form, and it creates an inclusive environment for discussion around community.

“Oftentimes with a lot of the folk artists that we work with, they don't even necessarily see their work as art that would be within the context of the museum,” Millar explained. “We're looking more at art that's rooted in community and talks about community.”

Changing Technology

The ways in which artists find professional success are changing alongside technology, as well. Shane Durgee, gallery coordinator for the Bevier Gallery at RIT, holds an MFA in studio art from RIT. He has observed his colleagues take a more “hybrid” approach to forming their creative careers, combining income streams from multiple artistic disciplines as well as teaching. Durgee also emphasized that social media is helping lesser-known artists get noticed.

“I think the internet is the big equalizer now, and things like Instagram and social media [make] the world so much smaller. That makes it so much easier to put your work in front of eyes that normally wouldn't see it,” he said.

There are still roadblocks to gaining access to the art world. Durgee explained it needs to be an effort on the part of gallery coordinators, the artists, the public as well as the powers in order for art to become more accessible.

“We still have this idea of the ‘right’ people and in front of the right collector and the right gallery owner."

“We still have this idea of the ‘right’ people and in front of the right collector and the right gallery owner. And I feel like that's what we are fighting, is the whole idea of that there's only one direction for your art to go,” Durgee said. “There needs to be other end goals and other ways to be successful and happy as an artist. And I think that comes back to discovering hybrid practices, thinking of combining ideas that haven't been combined previously.”