A Happy Mind is a Wandering Mind

by Victoria Sebastian | published Feb. 19th, 2020

You may be sitting in a lecture thinking about a funny story you heard earlier that day. Maybe you are driving and thinking about how to win a non-existent argument. Or maybe you are reading these words, thinking about something else entirely.

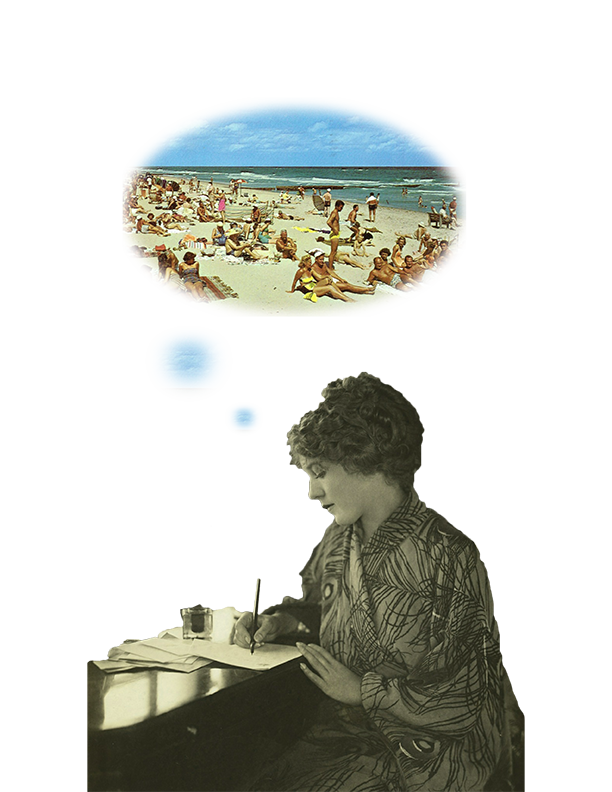

Photo illustration by Catherine Rafferty (Images from: needpix.com/Flickr)

Daydreaming is a common occurrence, yet many people try to avoid it. There is a stigma associated with the wandering mind that pins daydreamers as being unmotivated or careless. This stigma can be true in some cases, as Dr. Eric Schumacher, a professor of psychology at Georgia Institute of Technology, explained.

“There are social consequences [with daydreaming] ... it suggests that they don't care about what you are saying,” he said.

No one wants to see their friend zone out while they talk to them, nor does a professor want to see their students do the same. Therefore, we tell ourselves daydreaming is bad and should be avoided.

“Internally, people often feel like daydreaming or mind wandering is a failure of attention,” Schumacher said.

But, hidden in the shame and embarrassment of daydreaming lies the unspoken benefits of the wandering mind.

"People often feel like daydreaming or mind wandering is a failure of attention."

Schumacher's Study

In 2017 at Georgia Tech, Schumacher and then-graduate student Christine Godwin worked on a study about daydreaming. They were interested in the question: are there differences in mental capacity and brain functions for those who tend to daydream frequently versus those who do not?

Schumacher stated, “We had three kinds of measurements: how creative the people were, how intelligent they were, how efficient their brains worked — and we compared each of those measurements with their tendencies to mind wander.”

Their findings ended up contradicting the popular stigma.

He explained, “What we found was that actually more mind wandering during everyday life was associated with higher levels of creativity, higher intelligence and more efficient brain processing.”

"More mind wandering during everyday life was associated with higher levels of creativity, higher intelligence and more efficient brain processing."

What Does This Mean?

As the study suggests, when you find yourself daydreaming in class, it is not always a sign of disinterest. In some cases, it is an unconscious action that occurs when you already know or understand what is being taught.

“It’s a recognition that you have the ability to think of something else,” Schumacher said.

Therefore, in this case, daydreaming is a sign of intelligence.

First year University Exploration student Destina Amaya finds herself to be an avid daydreamer. In some cases, her daydreaming occurs simply because she is not participating in a challenging activity.

“I find myself daydreaming during very mind-numbing things. Anything that doesn’t take a lot of mental effort, I will probably start daydreaming,” she said.

Yet, higher intelligence is not the only thing that Schumacher and Godwin’s study correlated with daydreaming. A higher level of creativity was also found.

“While we cannot determine a causal relationship between mind wandering and creativity within our dataset, we can speculate about the mechanisms that may relate these two processes,” the study explained.

For many, daydreaming is a source of inspiration for their creative endeavors. Therefore, it only makes sense that the two relate.

“I find it common among people who write a lot,” explained Amaya.

Creative writing, painting, sculpture, music and such are activities that heavily rely on a creative mind. When most daydreams involve fiction and fantasy, mind wandering can be extremely helpful.

Both of these lead to the final fact of the study: daydreaming is a sign of efficient brain processing.

As Schumacher explained, “People with efficient brains may have too much brain capacity to stop their minds from wandering.”

When you are not being challenged enough and when creativity flows through you easily, what is stopping you from jumping from thought to thought?

This is only one study out of the thousands that tackle the topic of daydreaming, and more information is likely to come forward. For now, it is clear to see that daydreaming may be more of a skill than a hindrance.

Amaya’s Story

“People are different in how much their mind wanders during their daily life,” Schumacher said.

It is true that every mind is different, so the reasons we daydream and the amount of time we daydream can differ.

Although Amaya can relate to some of the study, her biggest benefit from daydreaming is that it helps her mental health. Her parents do not fully support her wishes for higher education, but she can’t help but follow the future she daydreams about.

Amaya explained, “It [daydreaming] is kind of how I plan out what goals and aspirations I have ... and the idea of that kinda keeps me going.”

“I do struggle with depression, and daydreaming kinda keeps me going."

Thinking about a future she is excited about makes daydreaming valuable to her. No matter if she gets in trouble with her parents, she finds it more helpful then harmful.

“I do struggle with depression, and daydreaming kinda keeps me going in the sense that I can always think about what’s going to happen next. I can always look forward to something,” Amaya said.

Therefore, the next time you worry about daydreaming, don't let the stigma get to you. As Schumacher and Amaya have shown, a wandering mind can actually be a happy, intelligent and creative mind.

Amaya said, “When I daydream, I believe I really am okay.”