Collaborating for Good

by Alice Rebecca Theibault | published May. 24th, 2019

Building Minds in South Sudan is an organization in Rochester working to educate the population of South Sudan, a country shaped by years of civil war. The organization was founded by Sebastian Maroundit and Mathon Noi, two cousins who fled war in South Sudan. They work to set up schools in their former home communities to enable that every child, regardless of gender or personal life circumstances, has a chance to reach their full potential.

This past year, several architecture students in the Golisano Institute for Sustainability had an exciting opportunity to assist in the mission of this organization by helping Maroundit and Noi design a brand new school. This collaboration was spearheaded by Dr. Nana-Yaw Andoh, an assistant professor of Architecture.

“I thought it was just a great opportunity for the students to do something socially conscious, to do something that would contribute positively to the world, and also to get a practical exposure — so being able to do a project that involved a real client, and a project that was going to get built,” he said.

Ultimately, the project has been beneficial to both the organization and to the RIT community.

Background

South Sudan is a nation in East-Central Africa, bordered by Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia. The climate is hot and dry, and the White Nile serves as its main body of water. The most urbanized areas in the country are found around this river.

South Sudan has a long history of civil war and marked attempts at independence. The nation has made two attempts to break free from Sudanese control, sparking two armed conflicts: one from 1955–1972 and a second from 1983–2005.

Maroundit was born in Warrap Province. In 1988, war broke out in his homeland, and his sister was killed during the fighting. Maroundit fled on foot all the way across South Sudan to Ethiopia, where he stayed for the next three years in a refugee camp.

In 1991, he and the rest of the refugees were forced out of Ethiopia and back to South Sudan. Eventually, they settled in another refugee camp in Kenya, where Maroundit would spend the next nine years of his life. This was the first time he was able to go to school.

In 2001, Maroundit was selected to come to the United States as a refugee, ultimately settling in Rochester. In his own words, the first thing he learned how to do in the United States was turn on a light. It took him five years to integrate into American culture, but eventually he became a U.S. citizen in 2007.

Eighteen years after being separated from his mother, Maroundit returned to South Sudan and was reunited with her and the rest of his surviving family members. He also met his younger brother for the first time. He was shocked to find that his hometown had no school buildings or infrastructure, and classes were taught under trees. Therefore, Building Minds in South Sudan was founded in order to address the lack of educational opportunities in the country.

The organization's website goes more in-depth about Building Minds in South Sudan's five primary goals:

- Building schools first locally, and then beyond.

- Providing equal opportunity for education for boys and girls.

- Advancing the human potential of the students.

- Providing villages with a school that can be the center of community organizing.

- Improving the quality of education in the nation as a whole.

Maroundit's program had a special interest in the goal of educating girls, as well. The first school that the program built was a coeducational school, and soon after an all-girls school was built in the village. In addition, through their Pads for Girls program, volunteers in Rochester sewed sanitary supplies for girls so that they did not have to miss school on their period. The organization even raised funds to purchase a wheelchair for a young woman, Angelina Awien Malek, who had lost the use of her legs due to polio.

In the United States, the organization spends most of its time trying to raise awareness and get funding and support from local community members and groups. The organization’s leaders have also given presentations explaining their story at churches, temples and schools.

Rochester-based organizations and individuals frequently provide Building Minds in South Sudan with financial support, but all the actual work of building and maintaining the schools is done by the people in South Sudan, using resources that are locally available.

Photo provided by Nana-Yaw Andoh

Collaborating with RIT

Andoh met Maroundit through a colleague, who had seen Maroundit present about the program at church.

“[Maroundit] approached me and talked to me about what he had already done and what he was trying to accomplish. And what they had done in the past was basically just a grassroots project; a community-led project to build something, and what he was looking for was some professional involvement, which is what I could offer with my students," Andoh said.

Maroundit had wanted Andoh’s students to help him design a new boarding school. To accomplish this goal, Andoh created an elective course for students in the architecture program. After discussing the overall plan with Maroundit, Andoh split his students into three teams, each charged with the task of coming up with a design that they could use. Diana Heliotis, a third-year graduate student in the Master of Architecture program, was leader of the team with the winning design.

“By ‘winning,’ it’s not so much that we created full-blown architectural documents; it was that they chose our design to try to implement into what they were building out in South Sudan," she clarified.

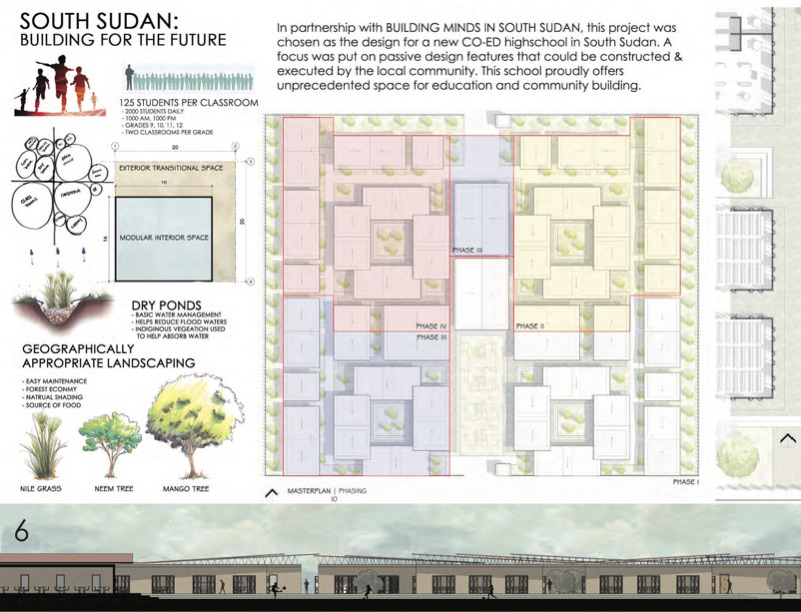

In designing the school, the students sought to create a holistic and self-sufficient space that could meet all the needs of the students and faculty who would be living there.

“We had to implement our design concepts that helped create natural ventilation, cooling, provide food on site through vegetation and implementing that into an educational design was really awesome," Heliotis said.

Heliotis and her team designed a modular structure consisting of a platform and an enclosed space, that could be built as many times and in as many sizes as necessary.

“The same shape could serve as dorms, could serve as a classroom, could serve as a cafeteria, office space, and all they had to do was essentially move it around in different ways on site to create different spaces ... It’s a simplified thing but it worked really well for us," she said.

The students also designed spaces to collect rainwater, including bioswales and rain gardens. The goal of this project was to enable the school to harvest as much water as possible during South Sudan’s monsoon season and enable them to grow their own food. Mangoes, which are native to South Sudan, were one crop that would be grown on-site. By incorporating native food plants into the campus, the schools will be more self-sufficient and provide more resources to the students.

Unfortunately, the students from RIT never did get a chance to help build the school, as they could not travel to South Sudan for safety reasons. Nevertheless, they learned a lot in participating in such a hands-on project. Andoh said he would love to do similar projects in the future, which might provide students with the opportunity to take part in the building. Andoh also stressed that the students' experience working on the project would make them better prepared for their future careers, as well as more attractive to employers.

Photo provided by Nana-Yaw Andoh

Challenges

Although the student all got valuable experiences with the project, many challenges were still present. Getting to know the people and culture of South Sudan, as well as their specific needs for school, was a challenge, as Heliotis pointed out.

“That’s one of the most important things in doing any sort of design in architecture, is doing research into where you’re building and who you’re building for. And that was actually one of the biggest challenges in some ways because schools in America are way different from what you’re gonna have in South Sudan," she said.

Andoh, who is from Ghana originally, explained how his knowledge of schools in Ghana came in handy for this initiative.

“I helped [the students] with the research to really get them to understand the daily commute and the daily life of a student who lives there [South Sudan] — how they get to class, where they eat, where they sleep, where they study, and also with some help from [Maroundit] to fill in the gaps between my knowledge of what I did in Ghana and how it relates to what happens in South Sudan," said Andoh. "It ended up that we were basically about ninety percent identical, so that worked out well.”

In Ghana, as in many African nations, school planners have to consider the needs of both daytime and boarding students, as well as living quarters for faculty and security for the vulnerable children entrusted in their care. Nevertheless Andoh was not, himself, an expert on South Sudanese culture, and so for several weeks his students conducted research on South Sudan, its history and its people.

Another challenge stemmed from the lack of available resources in South Sudan. South Sudan has relatively little resources and financial capital, even in comparison to many other African nations.

Sudan, South Sudan's neighbor to the north, has more infrastructure and at least one major city in the form of Khartoum, its capital. Nothing comparable exists in South Sudan. In part, due to this lack of infrastructure, it proved difficult to find both locally sourced building materials and labor, especially something high quality and realistic.

“We had to design something that the community had to be able to build," Heliotis explained.

Many of the engineering and architectural resources utilized in the United States were difficult or impossible to find in South Sudan, meaning that anything the students came up with had to be adapted to the local context.

The Fruits of Collaboration

All in all, the benefits of the collaboration between RIT and Building Minds in South Sudan have been overwhelmingly positive. Both groups are interested in seeing further collaborations into the future, as Andoh explained.

“When they approached us the idea was that this is the beginning of a bigger project," he stated. "This project we built is meant for a thousand kids but chances are two thousand are going to show up. So what they had done in the past was actually master plan an entire campus so that things were being built in a strategic way."

He expects to keep teaching the course, to enable future generations of students to participate in expanding and planning the school in South Sudan as it grows.

Heliotis added that she would love to continue being involved with Building Minds in South Sudan, or another similar organization, in the future.

“I think if it’s not this same one then something like it," she said.

Meanwhile, Building Minds in South Sudan continues to spread the word about their organization, and raise funds for their projects. Now that RIT has gotten involved, perhaps the organization will garner greater support and visibility. The students and staff in the Golisano Institute of Sustainability might end up as long-term partners. This initiative has proven a sterling example of what can happen when RIT and local charities come together to collaborate and accomplish great things.