The sun hangs high in the sky, overlooking the Golden Spike National Historic Park in Utah. The dings of a train bell can be heard, followed by the long toot of a train whistle. It’s a historic day: the 145th anniversary of the first transcontinental railroad, which was completed at the Promontory Summit in Utah.

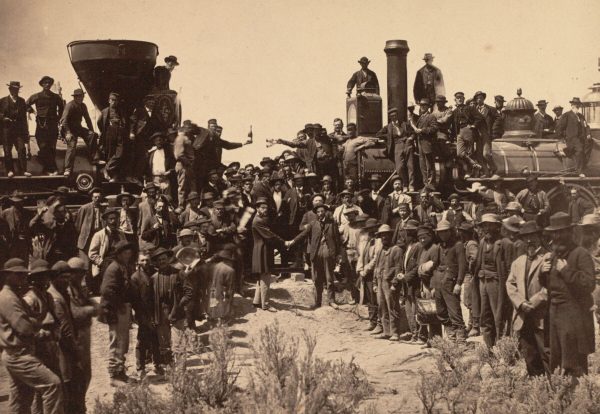

When thinking of the Pacific Railway, many look back to the historic “Champagne Photo”, which showcases two trains meeting, connected by the finished railroad track. Between the locomotives, the two trains’ engineers each hold out bottles of champagne to celebrate the occasion.

Almost 1,000 people were in attendance at this celebration, including politicians, railroad workers and members of the public. Yet, something was missing from this photograph. In fact, an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 of the Chinese immigrants who had built the railroad were missing from the photo.

145 years later, in 2014, things changed. Over one hundred Chinese Americans, some of whom were descendants of those Chinese laborers, stand in front of the trains. A voice can be heard above the crowd of people as they snap shots of the group.

“We’re Chinese Americans. We’re Asian Pacific Americans, so let me hear it! We came today to reclaim American history.”

That voice belonged to Corky Lee, the “undisputed, unofficial Asian American photographer laureate.” The self-proclaimed “ABC (American-born Chinese) from NYC” and activist spent over 50 years photographing Asian Americans in NYC. Throughout the years, he garnered over 800,000 photos documenting the diverse lives and stories of those who had often been overlooked and ignored by the mainstream media. Lee had first learned of the transcontinental railroad in his junior year of high school and noticed that the photo didn’t include the thousands of Chinese workers who had laid the 690 miles of track from Sacramento, California, to Promontory, Utah. This moment served as the inspiration for his life’s work. The transcontinental railroad recreation photo Lee organized wasn’t just something that needed to be done. It was an act of photographic justice.

Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story

Jennifer Takaki is the director of the documentary Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story, which was shown at the Rochester Theater at Innovation Square on Nov. 19, 2025. This 87-minute-long film tracks the “50-year history of Corky’s legacy, the struggles and the celebrations of the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) community,” according to Takaki. She first met Lee at an Asian American Journalists Association chapter meeting in 2003, after asking the closest person near her where the bathroom was. That person turned out to be Lee, and he began telling her the history of the building they were in. Drawn by Lee’s likability, Takaki decided to begin filming him for a five-minute vignette project. After she finished filming, however, Takaki realized that five minutes with Lee weren’t enough.

“When I looked at it and reflected on it, I didn’t think it was indicative of who he was and what he had done,” Takaki said during a pre-show interview. “So I just kept filming.”

For 19 years, starting in 2003, Takaki followed Lee around NYC, documenting his photographic journey across the city and beyond. Using his camera as a “weapon against injustice”, Corky chronicled the lives of the Asian American movement through the economic, cultural and political struggles faced by the community. His photos served to memorialize it all – the protests, the celebrations and even everyday moments.

“Corky was the most wonderful subject to follow,” Takaki said. “He never had an off button… He was just a fascinating subject matter.”

History of Activism

While Lee was the subject of numerous awards throughout his career, his work had gone unnoticed for a long time. Though that never phased him. In the film, John “Johann” Lee offers insight about his brother Corky Lee.

“He was doing the work he was doing literally for decades before he started garnering any kind of acclaim,” John explained. “He did it because it needed to be done.”

In the documentary, Lee cites a quote from President John F. Kennedy, who, during his inaugural address, stated, “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Lee took that to heart, as he poured years of his life into bridging art with politics and solidifying the space for Asians in the United States.

Outside of Lee’s photography-based activism, he continued to fight for his community. Along with other AANHPI activists, he lobbied for Congressional gold medals for more than 25,000 Chinese American World War II veterans, with one being awarded posthumously to his late father Lee Yin Chuck in 2021. Lee also helped in the creation of the first Chinese translations on New York City’s ballots in 1994. The city’s board of elections had refused to provide Chinese translations for candidates’ names in voting machines in districts where there was a large Chinese population, stating that there was simply no room and that the printers were unable to produce the Chinese characters. Lee would create a sample ballot for the board that included Chinese characters, which the board accepted. This monumental change helped to increase Chinese American participation in the city’s elections.

“When Corky put his mind to something, he would see things in the community that needed to be righted in his own way,” Takaki said. “And he could connect organizations, individuals, money, whatever was needed to make the change that he thought was important. No task was too small or too large for Corky to tackle.”

Lee also collaborated with numerous community projects and campaigned for NYC mayor John Lindsay with his lifelong friend and documentary co-producer Linda Lew Woo. Woo, the co-editor of the bilingual NYC publication Chinese-American News, met Lee in 1968, where she interviewed him for a Chinatown youth project.

Photographer and activist George Hirose served as the documentary’s executive producer and met Lee in the late 80s. During that time, Hirose worked as a photographer for the non-profit organization Henry Street Settlement, which provides social services, arts and health care programs for New Yorkers. Lee served as the representative for the printing firm that did the organization’s publications, which is how the two met.

“I heard from Corky that someone was making a film about him,” Hirose said. “…and I met Jennifer through some of the community organizations and things that we would do… You know, it wasn’t until after he passed away, though, that… I just needed to be involved.”

Photographic History

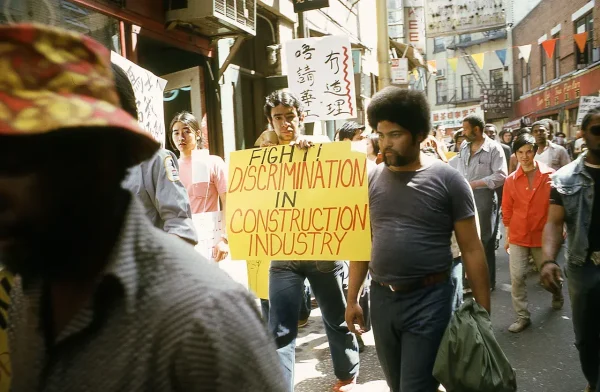

But Lee’s work didn’t just start in 2003. In fact, his activist-fueled photography can be seen as far back as 1974, during the Confucius Plaza demonstration in New York City’s Chinatown. The 44-story brick tower was the first major public-funded housing complex built mainly for Chinese Americans, and yet the building’s developer, the DeMatteis Corporation, refused to hire Asian construction workers.

Led by Asian Americans for Equal Employment, now referred to as Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), activists from Asian, Black and Latino communities marched at Confucius Plaza and forced a work stoppage. Lee was there, photographing everything. Weeks after the protest, the DeMatteis Corporation agreed to hire 27 minority construction workers, including Asian people. It was a big step forward for the Asian American movement, but it certainly wouldn’t be the end of racial discrimination for Asians in the U.S.

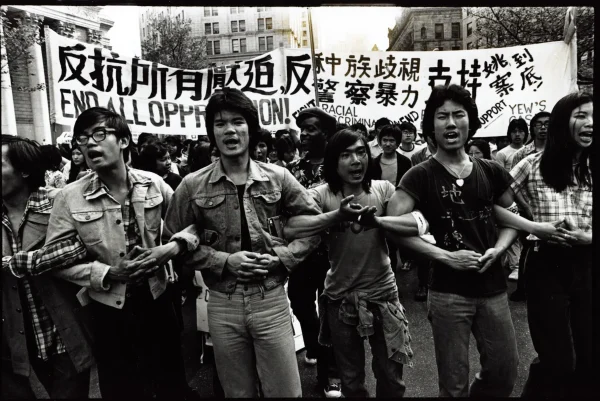

In 1975, a Chinese American named Peter Yew attempted to help and intervene when a 15-year-old had been pushed down by New York City cops during a protest crowd dispersal. In response, the cops detained, stripped and beat him, then charged him with resisting arrest and assaulting an officer. He had to be hospitalized for contusions and a sprained wrist. Lee, standing six feet away from the group, snapped a shot of Yew, holding his hand against his bloodied face as officers pulled him away from the crowd. After multiple attempts to submit his photo to news outlets, Lee’s picture was featured on the front cover of the New York Post in its May 19, 1975, edition.

That same day, Chinatown businesses closed as almost 15,000 marched through the streets, carrying signs that read, “END ALL OPPRESSION!” and “FIGHT RACIAL DISCRIMINATION. END POLICE BRUTALITY. SUPPORT YEW’S CASE.” Their message rang true as the community united not just to protest for Yew, but to protest against a long-upheld system of oppression that for years undermined and aimed to target Asian Americans.

Unfortunately, the hate and persecution faced by Asian Americans would culminate in the 1982 Detroit killing of Chinese American Vincent Jen Chin, who was beaten by two white men. The pair originally assumed that Chin was Japanese, and during that time, there was a high anti-Japanese sentiment spreading throughout the country, especially throughout the auto industry, as the two believed that the loss of American jobs was due to Japanese imports. One of the men was recently laid off from his autowork job and was seeking someone to blame; the two beat Chin with a baseball bat. Chin sustained heavy injuries and was declared brain dead at a hospital. Days later, he died, just a day before he was supposed to get married. The two men who had murdered Chin were each sentenced to three years of probation and were fined $3,000, with the judge, Charles Kaufman, stating that “these weren’t the type of men you send to jail.”

This rightfully sparked outrage among the city of Detroit, and Lee flew there to document the protests that began to take place. According to him, the protestors were diverse, including Koreans, Japanese, Filipinos and African Americans. All united under a common goal of aiming to see the two men who had killed Chin held accountable. In one of Lee’s photos, the protestors march with a large banner reading, “IT’S NOT FAIR!”, which were the last words of Chin before he lost consciousness in the hospital.

“I think the civil rights movement activism that occurred in the black community was a tremendous inspiration to the Asian American community,” Takaki said. “You know, they just saw that you could speak up and do things and change could evolve from that… I don’t think [Corky] just thought about the Asian American community. He really thought about anyone who had to fight for civil rights.”

Lasting Legacy

Corky Lee, the man behind the lens, passed away from COVID-19 on Jan. 27, 2021, in his hometown of Queens. He contracted the virus while documenting the Guardian Angels, a volunteer crime-prevention group, as they patrolled NYC’s Chinatown to prevent anti-Asian hate, since during the rise of COVID-19, there was an influx of misinformation that placed the blame on those who were Asian (specifically Chinese).

“Jennifer showed me a cut, and it didn’t take more than a second for me to want to help her finish the film,” Hirose said. “Because we lost a great friend. It was part of the grief process for me to grab hold and help him with his legacy, and he’s with us every day.”

The film ends with a quote from Lee stating that “the Asian American movement, I believe, is still alive. Whenever there’s a crisis, more people step up to the plate. You know, there’ll be setbacks, and there’ll be times that you’ll feel depressed about what’s going on, but you have to believe that things will get better. If you’re a photographer, keep shooting.”

Throughout his life, Lee served as a beacon of light and inspiration to not only his community but also to those who seek to make a difference.

“Whether it’s photography, whether it’s supporting a film, whether it’s if you’re out there as protestors, whatever that is that makes you feel that you have a voice in what’s happening and that you can do something,” Takaki said. “One person can make change happen.”

William Wong • Feb 2, 2026 at 11:40 am

♂️♂️♂️Thank you Corky Lee for everything you have done for the Chinese community!!!

Peg Lore • Jan 31, 2026 at 2:33 pm

There are others who are documenting the experiences of Asian Americans. But usually from a desk, academia, or a museum .I’m grateful to them. Still, I continue to miss Corky’s energy, bravery, and commitment to our communities as he sacrificed to capture stories /images on the frontline.

There is no doubt for me that Corky would be in Minneapolis documenting injustice now. Corky’s spirit and legacy is reaffirmed every time we see a photo that took years ago and is used today.