War. Genocide. Drugs. Violence. All things that students are exposed to across multiple subjects, but sex is where many draw the line.

In the United States, a very small percentage of middle schools and high schools — 18 and 43 percent respectively — teach material that covers key topics in sexual education as defined by the CDC.

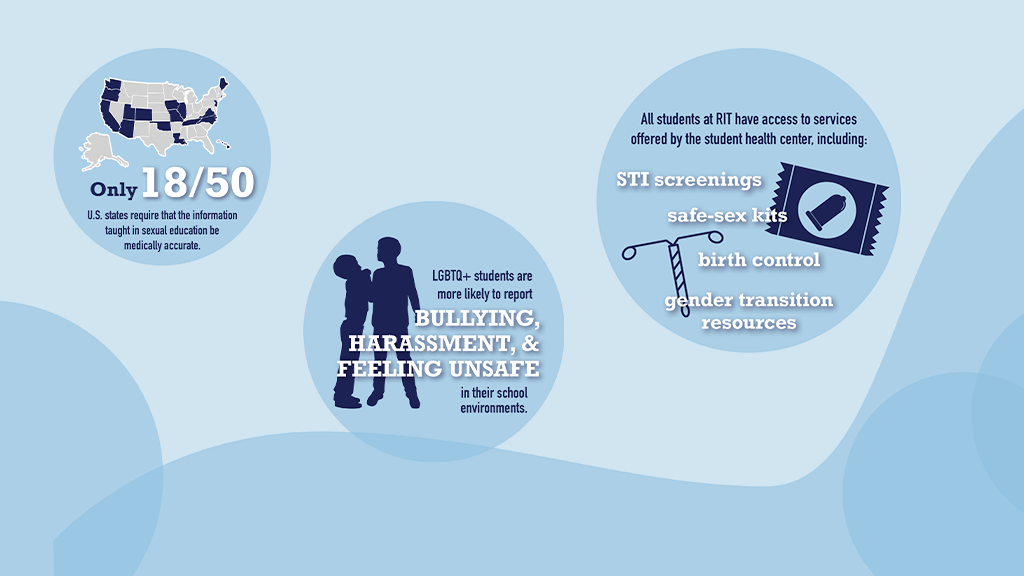

Additionally, only 18 of the 50 U.S. states require that the information taught in sexual education be medically accurate. Other states teach abstinence-only education, in which students are exclusively taught to avoid sex altogether.

Students are not being taught about sex, and this educational deficit goes beyond the mechanics of intercourse. Contraception, reproductive health, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and domestic abuse are all neglected topics by schools lacking sexual education.

For students identifying as LGBTQ+, the mental and physical risk can be even greater.

The Demand for Diversity

Chelsea Proulx, a public health researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, studies the impact of inclusive sexual education on students’ mental health and well-being.

In 2019, Proulx conducted a study examining schools with LGBT-inclusive sexual education programs and whether or not their students had better mental health outcomes.

Proulx’s model found that schools that had LGBT-inclusive sexual education programs experienced lower rates of depression and suicidality in both LGBTQ+ and cisgender heterosexual students, along with lower rates of bullying and harassment.

This research included statistics outlining the prevalence of same-sex couples in an area as a control value to soften the effects of experiencing more diverse or inclusive environments outside of school.

In the study overall, over twice as many LGBTQ+ students reported “prolonged feelings of hopelessness or sadness” than their heterosexual peers, and LGBTQ+ youth were five times more likely to attempt suicide.

Additionally, LGBTQ+ students were more likely to report bullying, harassment, and feeling unsafe in their school environments.

Even though schools may have gay-straight alliances or gender-sexuality alliances (GSAs), only a limited number of students actually attend those meetings. Students who may engage in homophobic or transphobic behavior are usually not a part of these organizations.

By including LGBTQ+ topics in general curricula, all students are exposed to these issues and may gain a greater awareness and understanding of the different types of relationships and gender expression in the world.

"[Inclusive sexual education] uses language that is very open and accepting, and definitions that are more inclusive."

If there is so much data backing up these claims and positive outcomes, why haven’t more schools adopted an inclusive curriculum?

Thinking of the Children

Many are familiar with legislation such as Florida’s HB 1557, nicknamed the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. The legislation bars all discussion of sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarten through third grade, or “in a manner that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate.”

Supporters of these bills argue that they are protecting students from grooming and predatory behavior by instructors, and question why children that young need to discuss sex in the first place.

Discussions of LGBT topics go far beyond just sex and general sexual education covers much more than sex itself. So what might an LGBT inclusive sexual education actually look like?

“It uses language that is very open and accepting, and definitions that are more inclusive,” Proulx said.

This could mean using anatomical terms instead of gendered ones, or having gender-neutral conversations about pregnancy. Many elementary schools already conduct early sexual education by teaching students about periods and their changing bodies, and most sexual education curricula is built around developmentally-appropriate topics for an age group.

“Kids that age are also old enough to understand what relationships look like,” Proulx said.

At this stage, inclusive sexual education may be as simple as teaching boys about periods as well as girls, teaching all students about different types of bodies and including same-gender couples in discussions about relationships.

As kids advance through their schooling, what material is considered “developmentally appropriate” advances as well.

Sexual education in a high school could include teaching about how pregnancy and birth work, methods of contraception and STI prevention. It can also cover life saving information on how students can self-check for breast cancer and testicular cancer.

“When we get to high school, I think talking about what safe sex looks like for queer youth ... [benefits] heterosexual youth as well,” Proulx explained.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, is a medication that can be taken by those at risk of HIV to prevent contracting the disease, either by sexual means or otherwise. Similarly, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) can be taken as an emergency measure after an individual has potentially engaged in intimate contact with a person with HIV.

However, PrEP and PEP are not typically mentioned during a sexual education program that focuses on heterosexual youth, as they are more commonly used by members of the LGBTQ+ community.

This is just one example of how inclusion of medically accurate and appropriate LGBTQ+ topics in sexual education can provide beneficial resources to cisgender heterosexual youth as well.

However, the barrier of policy remains, and with some states actively working against placing such programs in schools, the task of securing an equal education for everyone becomes more complicated.

An Educated Future

There is a gap in America’s education and inclusive, expansive, and medically-accurate sex-ed provides students with resources to make informed decisions about their sexual health and activity.

Most school curriculum is set at the state level, placing the decisions on youth sexual education in the hands of state legislators and education officials instead of doctors or sexual health experts.

“Talking about what safe sex looks like for queer youth ... [benefits] heterosexual youth as well.”

Inclusion doesn’t stop at sex-ed either. LGBTQ+ history and culture are a part of the United States that is often neglected by the material taught in schools.

“Sexual education can be a hard subject to advocate for … if we can integrate [LGBTQ+ topics] into any curriculum, we’re making progress,” Proulx said.

And what can we do when high school sexual education leaves lingering questions?

“Sexual education doesn’t stop at high school … Colleges should also think about making their communities inclusive with sexual education resources,” Proulx said.

All students at RIT have access to services offered by the student health center, including safe-sex kits, birth control, STI screenings and gender transition resources.

So get informed, get tested and bridge that gap as we work towards a country of inclusive sexual education, for everyone.