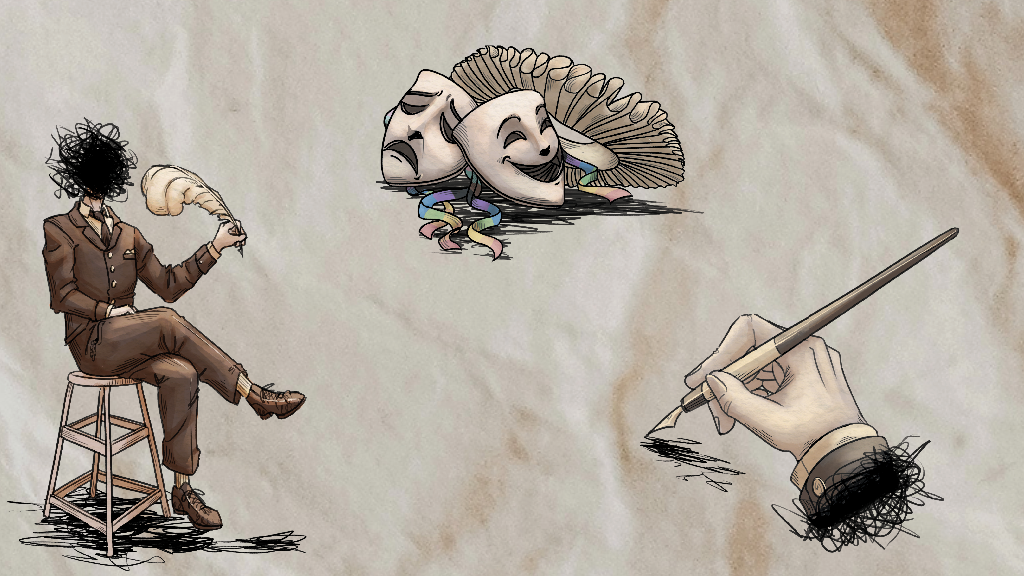

Literature interpretation has been taught all throughout the world. The goal in mind was to understand what the author's intent was above all others. That view changed in 1967, when Ronald Barthes wrote the revolutionary essay “The Death of the Author.”

Who Killed the Author?

Barthes’s essay pioneered a new way of looking at literature. Barthes argued that instead of focusing on the author and their life, the literature analysis should instead center on the text itself. Instead of looking for authorial intent, Barthes placed the reader's interpretation of a work above the author's.

Once the author releases their work out into the world they "die," and pass that ownership on to the reader. In their absence, readers are encouraged to lean towards their own interpretations of the text.

Literature is naturally open to interpretation, and people have different thoughts and understandings of the world around them. Two people can read the same thing and come out with two completely different thoughts and opinions about the material. If things were clear-cut and universally understood there would be no need for interpretations.

Robert Glick, an associate professor in the Department of English at RIT, explained how language plays a big role in literary interpretation.

“There's no such thing as a single meaning, there's no such thing as a single message.”

“What's key here is the theory of language itself,” Glick said. “There's no such thing as a single meaning, there's no such thing as a single message.”

Language is constantly changing as words are given new meaning. Something written 100 years ago can use words in ways that are radically different from how they are understood today. If we look back at the work of Shakespeare, there are plenty of words and phrases that carry a different meaning than at the time of writing than they do in the modern age.

“Words have multiple meanings. They change over time and connect to other words,” Glick said.

While “The Death of the Author,” was written with literature in mind, its ideas can be applied to all forms of media. The media landscape has evolved a lot since 1967, and movies and television shows have become as prevalent to our culture as literature was in the 1960s.

Personal Experiences

Personal experiences can also shape how people interpret media. Things that happened in our lives make us see the world in different ways.

"We're always bringing our experience to the table."

“We're always bringing our experience to the table,” Glick explained.

People's experiences shape the way they view a piece of media. An example of this would be how members of the LGBTQ+ community may view certain things differently than heterosexual, cisgender people because of the experiences they have had in relation to their identity.

“When I'm watching a movie, based on my experiences with other people, I can sense any character is gay,” Chase Moor

The LGBTQ+ community and media have always had a complex relationship. When analyzing media from a queer perspective, it’s worth bringing up "queer coding," a term used to discuss media with a character that is heavily implied to be queer.

This "coding" exists because of industry guidelines like the Hays Code and the Comics Code Authority, which put restrictions on what could be shown in media — especially in regards to LGBTQ+ related content. People creating media would work around these restrictions by putting implications, "codes," that a character was queer so the audience could pick up on it.

An example would be Mystique and Destiny's relationship in early "X-Men" comics. They were never explicitly allowed to be married, but writer Chris Claremont would heavily imply it through storytelling, such as the pair having an adopted daughter together.

“A lot of the time, queer coding is done by queer people,” Moore said. “It's done in a way that not just queer people [could] see through.”

While being queer is not necessarily a prerequisite to seeing a character as queer coded, having that experience can help people see the implications.

“If you are a person who's been in queer relationships, been in queer spaces and had a lot of queer friends, you would see the way that character acts and behaves [as queer],” Moore explained.

Queer coding does rely a lot on authorial intent and it isn’t the end-all for queer media interpretations. Many queer people can see a character and interpret them as queer without authorial intent.

Is There a Right Way To Interpret Media?

With media interpretation leaning more towards reader understanding rather than authorial intent, this brings up the question: is there a wrong way to interpret something?

The theory presented in “The Death of the Author” poses that when an author puts out their work, they lose all control over it. People, therefore, should be able to apply whatever lens of analysis they want to that piece of media. Even so, some people still hold onto authorial intent as the ultimate interpretation of a work.

The New York Times gave insight on why people value authorial intent. Some people don't see the point of viewing anything without authorial intent, because in their eyes, it enrichens the experience and is essential to understanding the body of work. You cannot have any creation without its creator.

Moore discussed why people don't care for authorial intent. Xe used the book “The Outsiders” by S. E. Hinton as an example. There are queer interpretations of the book, where readers view the characters as such. The author has taken a very firm stance against these interpretations of the book, but once a work is published the lines between authorial intent and personal reading begin to blur.

"The author's personal life is like meaningless in that sense," Moore said, in regards to Hinton's anti-queer sentiments. “People are just looking at the text and say: yeah, we can see this as being queer.”

If “The Death of the Author” is to be believed, the author holds no power over their work past publication. People have come to remove the author of their work, with stories like "The Outsiders" resonating with many fans in ways the author may not have intended. In a way, a work will outlive the author as readers make those works of fiction their own.