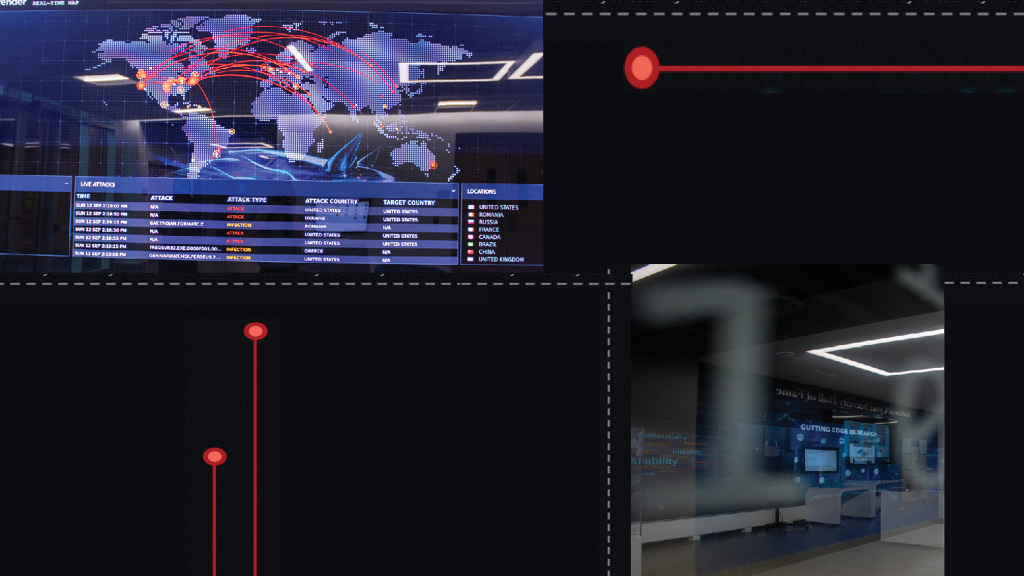

Fifty percent of U.S. technology executives believe that state-sponsored cyber warfare poses the most dangerous threat to their company or organization. Nation-state actors, hackers hired by countries to attack others, are all too common, with there being nearly a dozen zero-day exploits in the first half of 2020 alone.

These exploits refer to instances in which software developers learn of a security flaw too late and are left with zero days to fix the problem before it is exploited by hackers. As a result, this can allow them to cause damage to or steal data from a vulnerable system.

Forms of State-Sponsored Hacking

Associate professor in the Department of Political Science, Dr. Benjamin Banta, identified three categories of cyber attacks: physical damage, espionage and sabotage.

Physical damage cyber attacks are the only category out of the three that could be considered a full-on act of war if encountered.

“The most famous [case of physical damage] is the U.S. and Israeli use of Stuxnet to damage Iranian nuclear facilities,” Banta explained.

Unlike the viruses that came before it, Stuxnet inflicted physical damage on computers instead of simply stealing information digitally. By 2010, it had ruined a fifth of Iran's nuclear centrifuges, infecting 200,000 computers and causing 1,000 machines to physically degrade.

Espionage refers to the act of gathering information clandestinely. Also known as cyber spying, the act of stealing data costs between 25 billion and 100 billion dollars annually in the U.S. alone.

Sabotage represents a middle ground between the two former categories — in other words, an attack that damages a state’s infrastructure but doesn’t necessarily cause harm to human lives. However, an act of sabotage could still present a sufficient amount of catastrophe to a state.

The tricky part about cyberwar is that it's difficult to determine which of these categories a certain attack fits under.

Director of Global Outreach for the Global Cybersecurity Institute and professor in the Department of Computer Engineering, Dr. Jay Yang, shared insight into what may be the most common form of state-sponsored cyber attack.

“There is also hacking that’s not necessarily hacking into computers, in the sense that it’s more of a social media disinformation campaign,” he said. “It affects our way of thinking, decision making or interpreting of facts.”

State-sponsored disinformation distinguishes itself from propaganda through its main goal: to confuse the public with multiple messages as opposed to pushing a certain ideology. For example, the spearheading of massive disinformation campaigns attempting to alter the narrative of COVID-19 in the U.S. has caused the country to see a largely disproportionate death toll relative to its global population. Campaigns such as the one previously mentioned can enable disinformation to become much more dangerous than propaganda.

In addition to online disinformation, the most frequent targets of cyber attacks affiliated with foreign states include the financial banking industry, utilities — power plants, electronic modding systems, etc. — higher education, healthcare systems and supply chains that could ultimately lead to government agencies.

The Gray Area

The process of determining the motives of a cyber attack, or whether it was indeed state-sponsored, is one that remains engulfed in ambiguity.

“That’s the real advantage that cyber attacks ... can give to any state,” Banta said. “You can do it and hide your tracks, at least for some period of time.”

In the modern era, states that have advanced their responses to cyber attacks, including the U.S., have improved their ability to identify hackers.

When deciding how to respond to a state-sponsored cyber attack, the severity of the attacked country's response should never be overlooked. Even if a cyber attack doesn't take human lives in the immediate, there's no telling the long-term damage it could cause.

“Ones and zeros, bits and bytes, are just as physical as anything else, and especially the damage they can cause can be just as physical,” Banta stated.

“Ones and zeros, bits and bytes, are just as physical as anything else, and especially the damage they can cause can be just as physical.”

Identifying Ethical Solutions

As companies and organizations decide how to best defend themselves against cyber attacks, the importance of participating in anticipatory defense strategy and observing early symptoms before an attack occurs cannot be underestimated.

“There are certainly technologies being researched ... where machine learning [is] used to predict what [an] adversary might do, and computer and networking systems are changing to make it hard for [the] adversary to penetrate,” Yang explained.

While newer technologies are being utilized to enhance cybersecurity, it's also important to enact policies that focus on safe standards of behavior.

“We need to continue emphasizing human cybersecurity hygiene practices, such as not clicking on unknown links, applying security updates, using stronger authentication methods, turning off WiFi and Bluetooth when not needed," Yang added.

However, cyber security will always present some level of risk, and unfortunately, this comes with the territory.

“There’s no 100 percent cyber security system, because the [foundation] of the Internet or the cyber world is to enable remote access," Yang said. "If you want to enable remote access, you will have some flaws somewhere.”

“There’s no 100 percent cyber security system, because the [foundation] of the Internet or the cyber world is to enable remote access.”

Certain defensive cyber operations have raised red flags within the computer security community in debates regarding ethics and legality.

“[The U.S. is] actually actively hacking into all kinds of actors out there that they suspect might have malign intentions on U.S. corporations or the U.S. state,” Banta said.

Although a country might not cause any damage in doing so, this could appear as a violation of another government's rights and lead to retaliation as a result.

As the threat of state-sponsored hacking continues to loom over the world, it still may take long before further damage is prevented.

“I think we’re in for the next decade of muddling through this until the damage becomes great enough that the powers that be — great powers like the United States and China — are willing to sit down and say, ‘Okay, let’s put some restraints on this,’” Banta said.

Until then, these kinds of cyber attacks will continue to wreak havoc at an alarming rate.