Content warning: This editorial contains language that may be a trigger for those closely associated with sexual harassment, stalking and sexual violence.

Initially, this was going to be a piece highlighting RIT’s Public Safety department and their relationship to the greater student community. I was directed to Public Safety’s annual security report, a document showcasing reported offenses. Outside of the typical drug and alcohol offenses, there was very little on reports of sexual assault or stalking.

It should be a good thing that there are so few reports, right? But there is a distinct difference between those who report, and those who don't.

With the rise of #CampusLife on RIT's reddit, it’s essential to understand why victims often refuse to report or drop the case, and how often this happens.

The Filing Process

There are many reasons why someone would not want to report an incident. For some, the process is just too long.

From starting the report, to collecting evidence and to preparing a case, there are many things that can go wrong. Even during court, there are a lot of obstacles victims must face to find justice.

It’s an incredibly draining process, and if evidence isn’t kept or preserved, sometimes there’s not much RIT or law enforcement can do in pursuing the case. Not to mention the stress it’ll cause for the victim who will need to relive their experience over and over throughout the process.

This is just in reference to a generic case as well, not even mentioning what comes from more sensitive cases such as harassment, stalking or even rape.

For some stalking cases at RIT, the victim may not even know the perpetrator’s name, so there is even less that can be done. Of course, victims can utilize their support groups and have a buddy system where someone is always with them throughout the day. But asking someone to keep walking you to class rather than getting the stalker to stop harassing you is frustrating and demoralizing.

However, that still doesn’t explain why there aren't many reports for stalking and harassment when it seems like a distinct problem on campus. One part that could explain this is the consistent phenomenon of underreporting, where victims are reluctant to report the crime for a variety of reasons.

A big aspect of underreporting is how often victims are afraid to report crimes in general, because of the way society treats them.

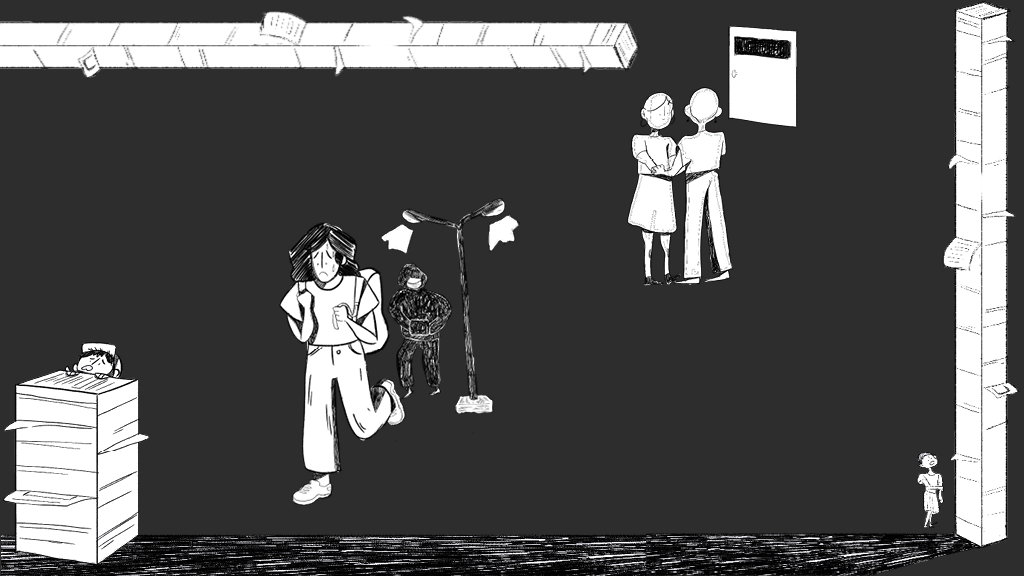

An Isolating Experience

Some of the most common reasons why victims don’t report crimes against them is shame from the crime happening to them, fear of backlash from the perpetrator in reporting the incident, lack of belief of police and doubt that the crime actually occurred.

Especially for victims of sexual harassment or assault, there can be a sense that maybe the victim could’ve been prevented the crime themselves. This is reinforced by external forces such as society, or even their peers, when people discuss assault. They ask what kind of clothes the victim was wearing, ask whether the victim was drinking during the incident, whether the victim was provoking the perpetrator — these kinds of questions are pointed to the victim, blaming them for something that was outside their control.

"The Red & Black" is a publication that followed the events of a series of 2020 tweets following various University of Georgia students and alum about their experiences with sexual harassment, assault and rape. They interviewed various sources that were sharing their stories, as well as some who were accused.

One of their sources explained how, after the assault, they couldn’t put a finger on what happened to them, until people started coming out about their experiences.

“I knew [the assault] wasn’t right, but I just didn’t have the words to understand what exactly had happened to me,” the anonymous source, coined as Crystal, reported.

"I just didn’t have the words to understand what exactly had happened to me.”

This kind of dissociation to the event, and inability to connect the action to the word is a common response to traumatizing experiences such as assault. It’s one of the many factors of why sometimes reports can take years before the victim speaks up, such as the case with Brett Kavanaugh and Christine Blasey Ford.

Knowing that these events happen so often and are left unspoken and hidden, what can we do — as individuals and as a community — for each other?

A Story Without an Ending

With the amount of people that came out to share their story through @ugasafespace, an anonymous Twitter account that shared stories of sexual assault victims, people thought some change would happen at the University of Georgia.

“So many survivors came forward and then when we realized we’re coming forward en masse, we were like, ‘Surely there’s going to be some kind of action, some kind of accountability,’” another source from "The Red & Black" explained. “But ... nothing happened.”

"‘Surely there’s going to be some kind of action, some kind of accountability ... But ... nothing happened.”

Even with a movement and so many students coming out, change often does not happen. Students are still left with the events that occurred and are left alone to unpack it.

Administration may wait until the event tides over and never speak of it again. Even if changes are put into place, such as RIT’s mental health teams, there's an uncertainty to whether these institutions will work.

So how can we solve this problem that’s been an issue for so many years, in so many communities?

This is a systematic problem, a problem that has impacted one out of six American women and one out of 33 American men. How can we even think to combat that, as individuals, when we as a society still haven’t figured it out?

The first step, out of many, is to sit down and listen.