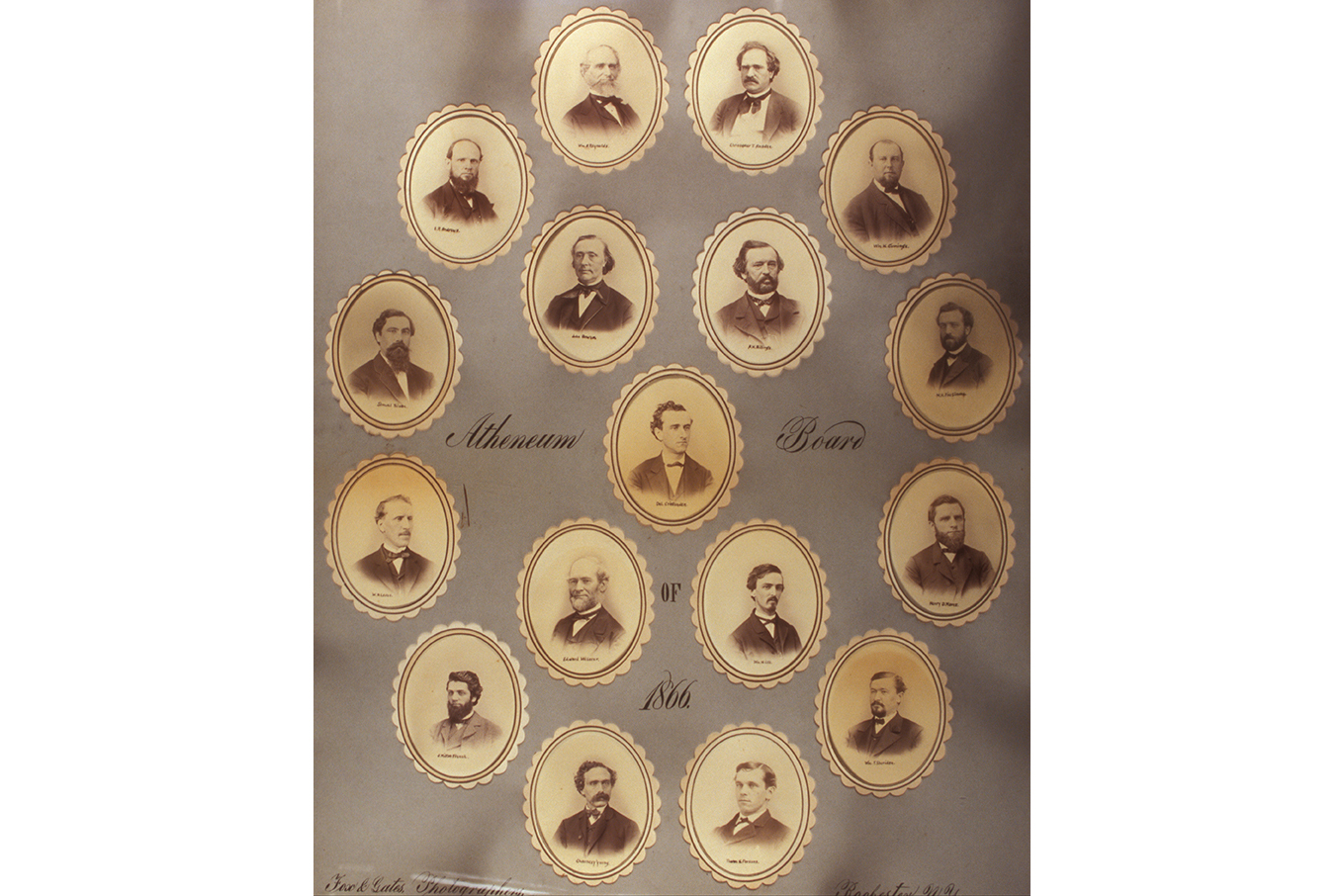

The year is 1829. On the second floor of the Reynolds Arcade in the newly formed city of Rochester, a group of townsfolk has gathered to watch a lecture by an author visiting from England. In a small area towards the back, a few older men are speaking among themselves, all familiar faces around the hall. Abelard Reynolds, Charles Perkins and Nathaniel Rochester are discussing the future of their organization, the Rochester Athenaeum, known today as the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Reynold’s Arcade circa 1829. Image courtesy of RIT Archive Collections.

When talking about the early history of RIT, the Rochester Athenaeum is briefly mentioned if at all. This cultural and intellectual center of the city has fallen to the wayside in service to the story of a trade school elevated to the status of a technical university. However, despite a lack of attention, the effects of the Athenaeum on Rochester, RIT and education as a whole are difficult to overstate.

The Franklin Institute

In the early 19th century, education was seen as a way for the upper class to gain an understanding of literature, history and philosophy. Because of this view, there were few ways of gaining a formal technical education. Dane Gordon, author of the book “Rochester Institute of Technology: Industrial Development and Educational Innovation in an American City," explained further.

"Many young people wanted the opportunity to study, and people wanted to improve their lives through education," Gordon said.

In an effort to raise capital, a group of scientists and engineers who called themselves the “Chemical Class” invited Sir Eaton of Troy to give a lecture in the then village of Rochesterville. This event was wildly successful, with so many people in attendance they had to reorganize the furniture in the hall. Using the surplus revenue from the event, this group would found the Franklin Institute.

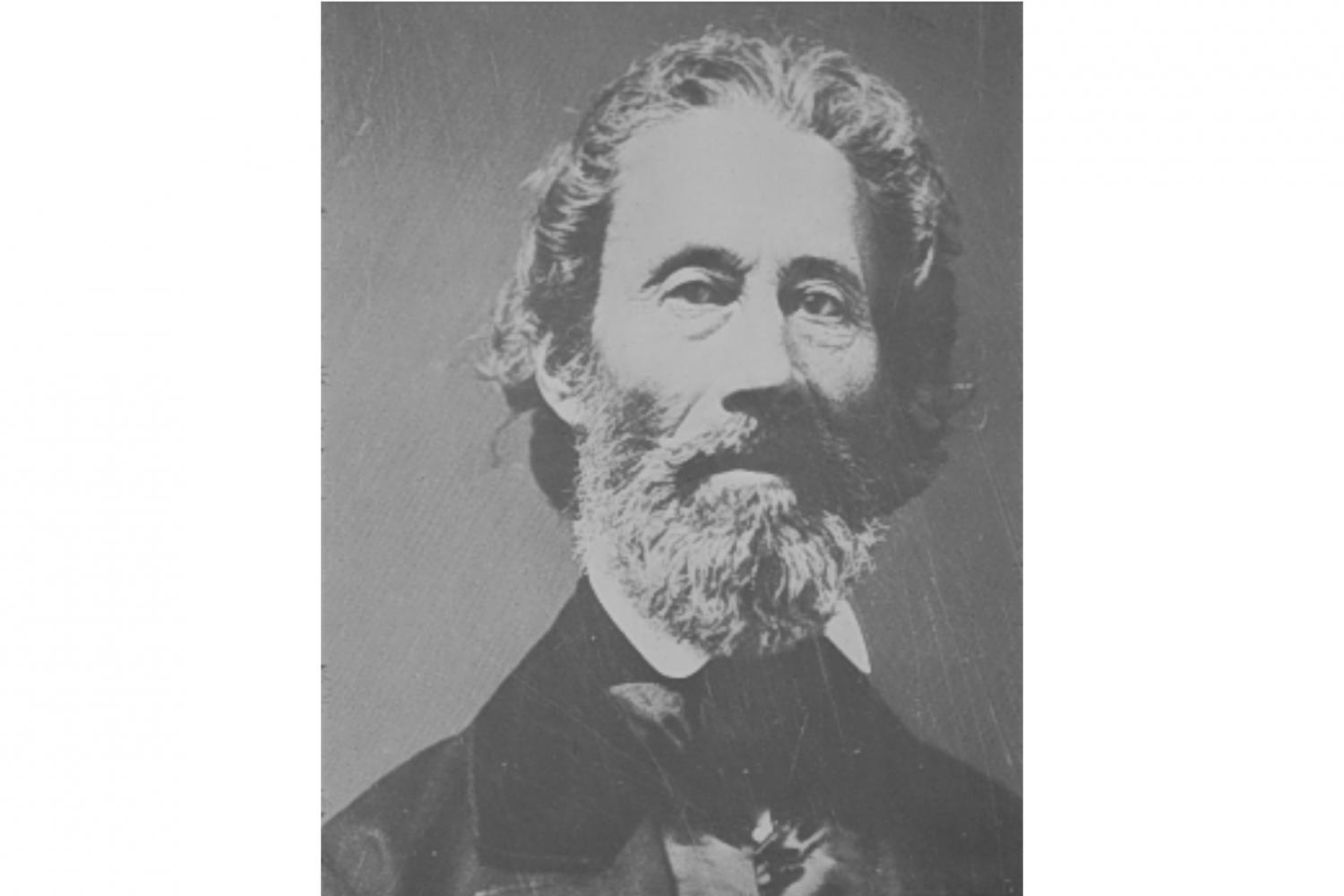

Col. Nathaniel Rochester circa 1800-1831. He was the founder of Rochester as well as a co-founder of the Athenaeum, the earliest form of RIT. Image courtesy of RIT Archive Collections.

The Franklin Institute was one of the only groups of its kind at the time, providing an education in more tangible skills and being one of the only places for young people to learn about literature, philosophy and history, as well as hands-on skills within the newly formed city. However, external influences would soon cause it to crumble and lose many of its key members. Some of those who left chose to form a new organization in the nonpartisan spirit of the masonic lodges, establishments from England where Freemasons would study under each other in order to reach different degrees of masonry. This new group, led by Nathaniel Rochester, would go on to be the original members of the Rochester Athenaeum.

The Impact of the Athenaeum

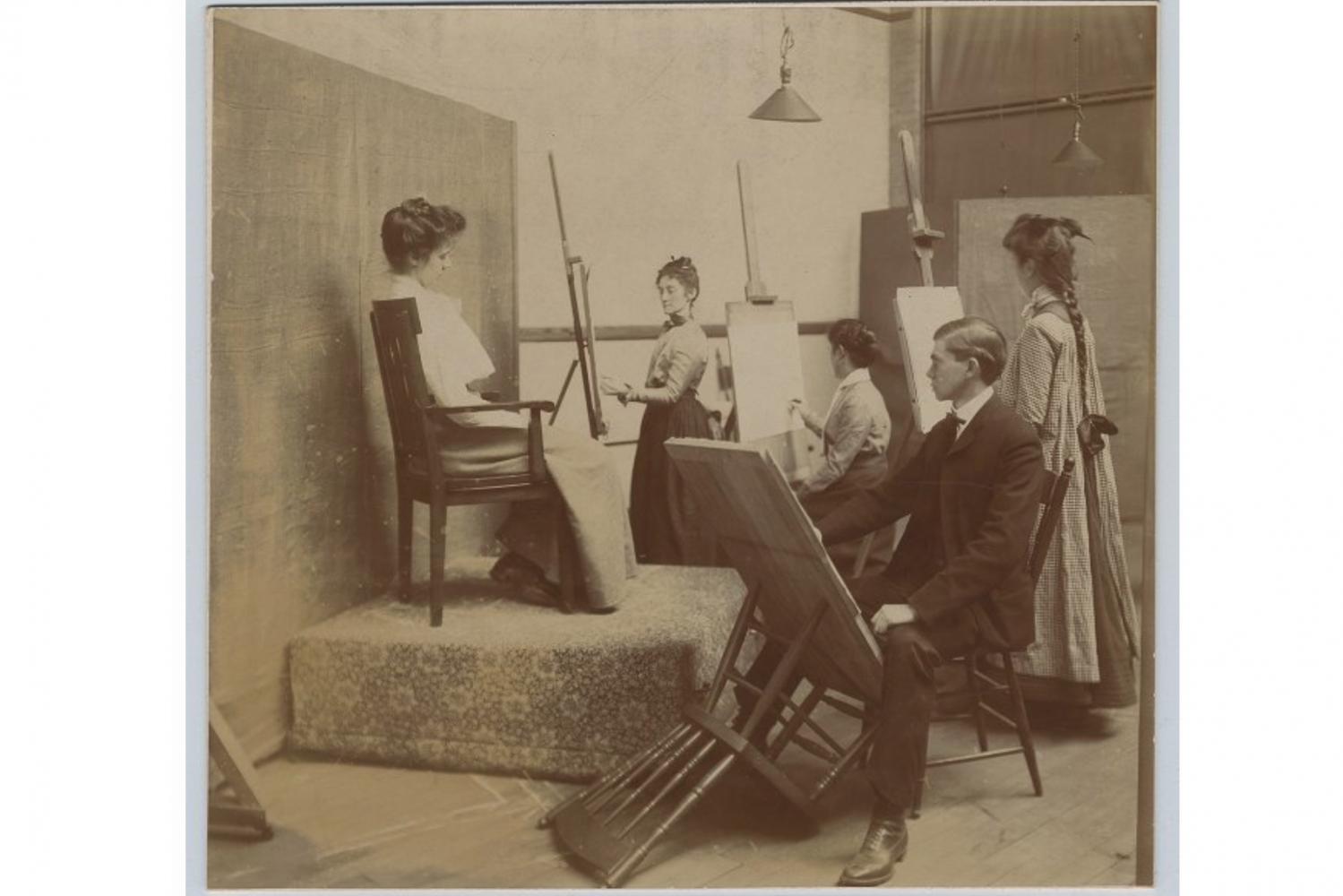

Unlike the more practical nature of the Franklin Institute, this new organization put the humanities at the forefront. Although a practical education was offered, it was almost always supplemented by a basis in the humanities. Soon the Athenaeum would become the center of Rochester’s intellectual community, hosting guest speakers every Tuesday and Thursday evening including Charles Dickens and Daniel Webster.

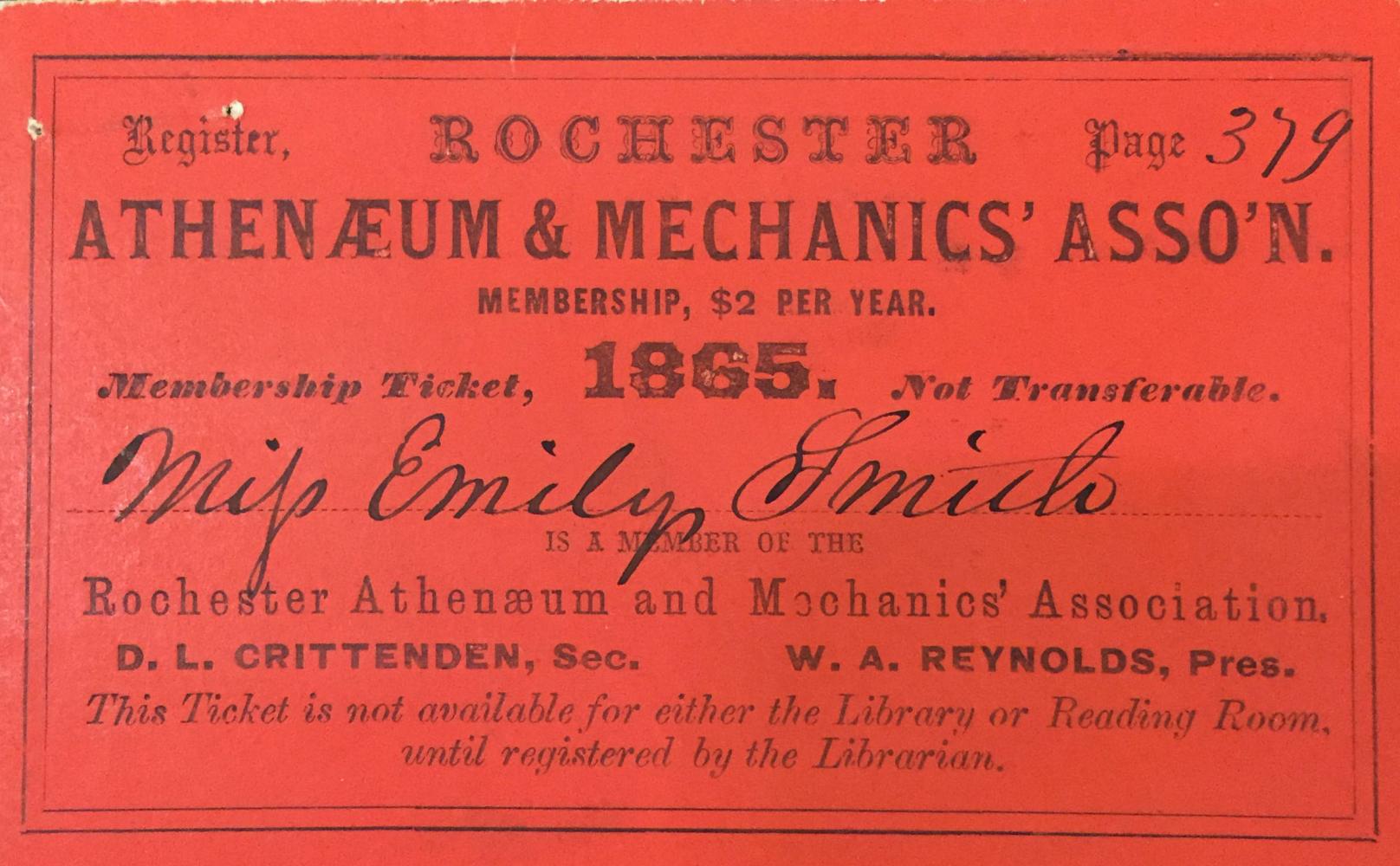

The Athenaeum’s library was also very well-stocked for the time with many of its wealthier members donating volumes from their personal collections. A bulk of the money from dues collected each month went towards subscriptions to the foremost newspapers from not only the United States, but also from overseas. A scrapbook of subscriptions to journals and newspapers housed in the RIT archives shows that in their first year of operation they spent at least $1,000 in literature alone, which amounts to over $20,000 after inflation.

In many ways, the Athenaeum challenged the idea of what education was meant to be in the 19th century. Instead of a place for the rich to enrich themselves, the Athenaeum’s low cost of entry and public lectures made education accessible to the public. It became the center of a debate between the true purpose of education in civilized society and in its pursuit of the answer, created an intellectual institution ahead of its time.

"They wanted people to learn things they could apply to their lives and earn a living with," Jody Sidlauskas, associate archivist at the RIT Archives, said.

The organization was also integral in the early development of the city of Rochester itself. So much so that meetings were held in the Reynolds Arcade, a hall on the second floor of the post office, owned by the first postmaster of the city. Many people who studied at the Athenaeum went on to assist in the construction of some of the city’s greatest landmarks, helped to change Rochester from the “Flour City” to the “Flower City” and worked to build up much of the infrastructure that enabled Rochester to grow into the center of industry and development it would become later on.

An Organization Ahead of Its Time

Despite many of its contemporaries falling to the wayside and being forced to disband, the Athenaeum managed to maintain relevance throughout the century. It was able to grow and change with its society and a lot of that was due in part to the absorption of and mergers with groups that resonated greatly with the populus. The first of these major mergers was with its own predecessor, the Franklin Institute, which had fallen on hard times due to partisan infighting.

The horizontal integration of the other academic societies by the Athenaeum created an organization where the young were welcomed more than the old, and at a time active members couldn’t be over the age of 25. However, the infusion of new ideas into the organization lead to revolutionary new ideas on education, which came to a head after the Athenaeum’s merger with the Young Men’s Association in 1838. Henry O’Reilly, the founder of the Young Men’s Association, was one of the first people to understand that people wanted to be entertained as they learned new information. After the merger, he opened the evening lectures to the public and organized a series of more specialized speakers.

The foundation that the Athenaeum provided was invaluable as RIT progressed in its history.

"In 1891, we couldn't have started with the history and knowledge that the Athenaeum gained over the years," Sidlauskas said.

A Lasting Legacy

The Athenaeum was an integral part of Rochester’s development as a city, and it provided one of the only kinds of education for much of the 19th century. While not commonly known, this holistic education was a foundation for RIT.

"It is assumed that RIT was formed from a trade school, and that is just incorrect," Gordon said.

As the organization grew and changed, it brought industry and progress to the once small grain city. Even after it was absorbed by the Mechanics Institute in 1871 and lost much of its autonomy as an organization, the supply of engineers, scientists and businessmen played an integral role in growing companies like Kodak Eastman and Xerox.

"RIT's campus remained in the downtown location until 1968 and so the whole time it was in that location, members of all the large corporations Kodak, Xerox and Bausch + Lomb were on the board of trustees and so there were partnerships going on with co-ops, internship and development of courses based on what these companies needed for their workforce," Sidlauskas said.

The growth of the Rochester Athenaeum and Mechanics Institute into RIT was explosive, and a lot of the time, the earliest origins are ignored for the more compelling story of a small trade school that built itself up through merit and hard work. However, even after the name of the school was changed to RIT in 1944 and the campus was moved from its original location in downtown Rochester, the spirit of the Athenaeum still remains in the Liberal Arts department at RIT to this day.

“We are all whole people, not just engineers, chemists or biologists, and as whole people we require a whole education to truly experience life,” Gordon said.

This is not only sentiment about what RIT needs to be in order to best serve its students, but it is also a perfect impression of the mark left on RIT by the Rochester Athenaeum in its pursuit of a holistic education since its very beginning.