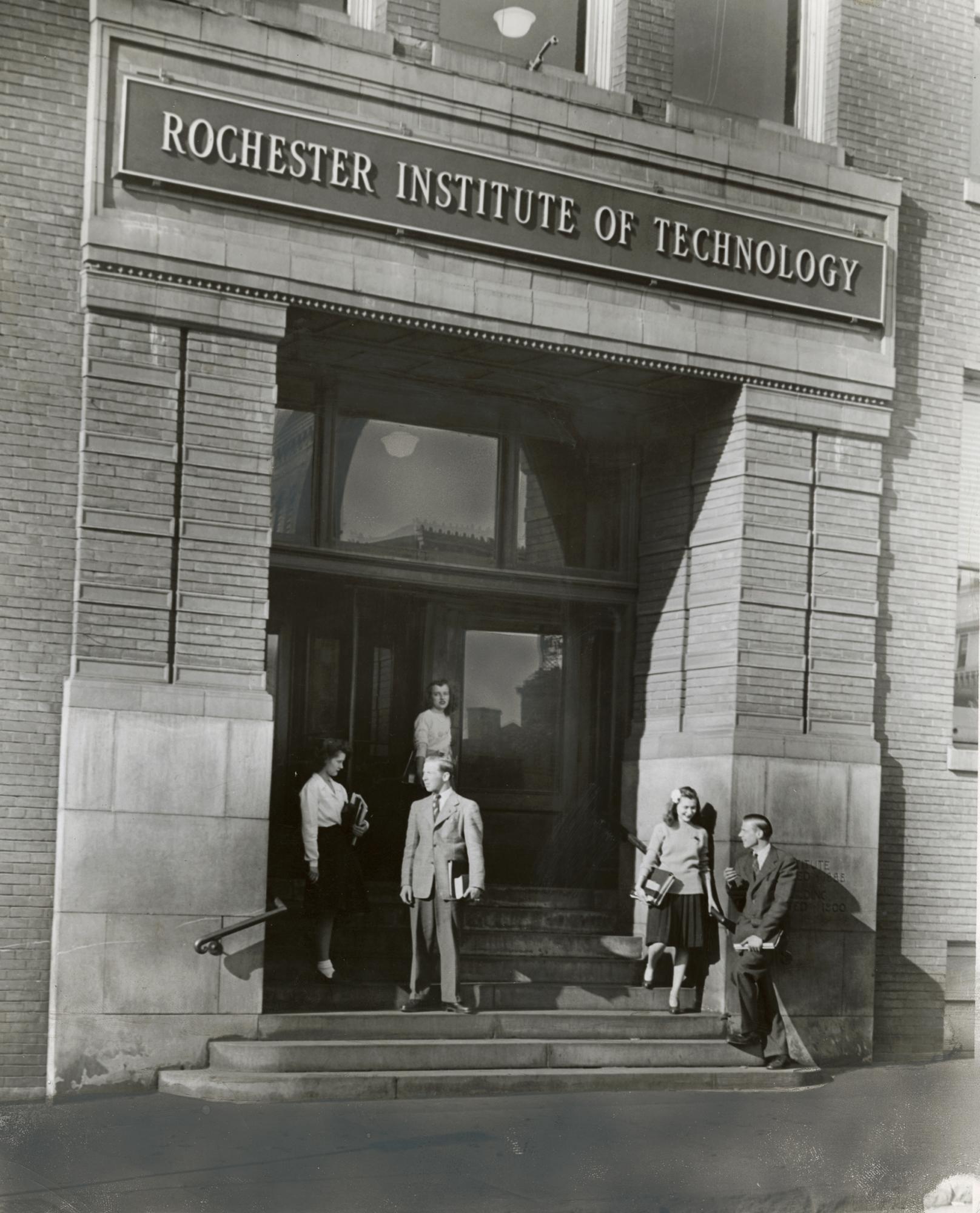

For most of us, it is hard to imagine RIT existing anywhere besides the suburb of Henrietta. But only 50 years ago the campus was located in the heart of downtown Rochester. Then, the city was a relatively prosperous metropolis. Innovative high tech businesses such as Kodak and Xerox fed a flourishing economy grow rapidly, giving early Rochester the nickname “Smugtown USA.” However, a changing economic and social environment eventually pushed RIT to the suburbs.

Early History of RIT

Michael Brown, assistant professor in the History department, explained that early Rochester's heavy manufacturing and technology-based industry also required a highly skilled workforce.

"There was a need for institutions like RIT to prepare workers to enter the local workforce with a set of technical skills for the type of production that took place in [Rochester]," Brown said.

During the 1950s, RIT experienced a huge influx of student applications and attendance. Director of Planning, Design Services and Construction Services James Yarrington explained that besides the job opportunities, entertainment was one of the reasons more students became attracted to Rochester. According to Yarrington, while RIT was located in the city, students could enjoy a vibrant nightlife that included a lot of jazz venues

“Rochester was quite satisfied with itself and thought it was flourishing, but that wasn't across the board. Between RIT's announcement to move in 1961 and its actual move in 1968 was an event called the 1964 race riots,” Brown said. "[The race riots] had two geographical centers. One was in the northeast and one was in the southwest just on the cusp of the downtown campus."

On top of a social crises, Rochester was also going through a period of urban and highway construction, Brown explained.

"Rochester, like other older cities, was going through a profound period of changing the urban renewal and highway. It was a time when people who did have those decent paying jobs in the corporate section were moving to the suburbs," Brown said. "Emigration from the city attracted middle class, predominantly white Rochesterians."

Sarah Thompson, associate professor in Art History, is currently working with RIT Archivist Becky Simmons on a photography-based book about RIT's 50th anniversary. Thompson explains some debate the RIT Board had at the time of the crisis.

"RIT knew they had to do something because the highway was going to tear down parts of the campus ... They had to choose between trying to cobble a kind of solution downtown and try to expand or try to start over altogether."

"RIT knew they had to do something because the highway was going to tear down parts of the campus. They were also in a period when they were experiencing huge growth ... They had to choose between trying to cobble a kind of solution downtown and try to expand or try to start over altogether at a new site," Thompson said.

The Inner Loop was controversial because it required the demolition of many buildings in the city and segregated downtown from the rest of the city. One of those buildings listed for destruction was the Eastman building, RIT’s primary academic building at the time.

According to the RIT Archives Collection, RIT had already committed to expanding downtown into 50th W. Main St, but now they knew they wouldn't have enough space. At the same time, consumer demand for Kodak and Xerox also went into decline, casting further doubt on the future of RIT's Rochester campus. An unexpected gift left in the will of Grace Watson finally persuaded the Board of Directors to move to Henrietta.

RIT's departure from the city in hindsight was arguably very well timed. The city deteriorated drastically in the 1960s from combinations of social and industrial changes. No longer able to keep up with the changing global economy, Kodak began downsizingin the 1980s, the first wave in a series of layoffs that would go on for 37 years. The high skilled corporate economy that Rochester was known for almost completely disappeared. The population of the city continued to decline in favor of the suburbs from its peak in 1950 at 332,488 to only 208,880 in 2016, according to Biggest US Cities. If RIT had stayed they would have been in the midst of a dying utopia.

The Henrietta Campus

The decision to move to Henrietta was made in 1961, three years before the race riots, but rumors always circulated that RIT was intentionally designed without a central square to avoid large protest gatherings. With protests occurring on many campuses, Yarrington admitted that some campuses designed in the 1960s may have “shied” away from building a central square to avoid involvement in the Civil Rights movement. However, he pointed out it was also a trend for modernist styles. Other architectural historians don't believe that avoidance of the Civil Rights movement was a factor at all in the design of the new campus.

“At RIT, crowd control didn't enter the discussion. When you go through the archives, there are conversations about separating living and work spaces to give residential students some peace and quiet (RIT had a big night school population then), about using the easiest land to build on (two areas of higher ground), and about connecting the living and work areas with an axis (now the quarter mile),” Thompson said, countering the rumors of the RIT anti-protest theory.

As noted before, RIT buildings also have a very modernist appeal. The style is close to Brutalism, a term originating from French that means “raw.” Brutalism uses heavy, strong geometric shapes and forms meant to convey "brutal honesty and tactile focus," Thompson explained.

Over the years, this style has become less popular and was conflated with authoritarianism. Although RIT stopped short of the extensive use of concrete often employed by traditional Brutalist architecture,the campus has received criticism for being ugly, outdated and “cold-hearted.”

"RIT is pretty unusual that they developed the idea to hire internationally known architects of the period to collaborate with each other."

The goal was to present the university as a modern technology school that was unified under a central design, which ironically was achieved by hiring five different architects.

"RIT is pretty unusual that they developed the idea to hire internationally known architects of the period to collaborate with each other," Yarrington said.

According to Yarrington and Thompson, to make sure RIT had a unifying appeal, RIT commissioned architects from all over the nation to collaborate on the designs for the campus. . There were a total of five architects and one landscaper, all with Ivy League degrees in architecture and previous experience in university campus design. Lawrence Anderson, the organizing architect, oversaw the general project and delegated responsibilities by different colleges and focuses. This back-and-forth process to ensure the consistency of the campus' overall design was tedious, but eventually resulted in the cohesive style that we recognize today.

RIT’s architecture is known to be constantly evolving. As the campus expanded, the architects wanted the buildings to have an “architectural conversation” with each other, but retain an individual design which represented each distinctive era that inspired the building, ranging from the 1800s to modern times. For example, brick and tinted windows were used initially for energy conservation reasons. However, recent developments in glass allows for newer buildings to be more transparent but still energy efficient, such as in the currently developing MAGIC center. The transparency and light-based buildings are also representative of RIT’s shift from heavy-machinery engineering to research, medicine and sustainability.

"We're very consciously over the years carefully and sensitively evolving RIT's architecture," Yarrington said.

Expansion in the Future

Clearly RIT had many reasons to move to Henrietta; however, constructing on a swamp proved to have its challenges. RIT is built on wetlands and is practically surrounded by a moat, so construction locations had to focus on areas of higher ground.

"When I first came to campus, we had some wetlands mapped by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, but that was more limited in area and scope. But, the New York DEC-mapped wetlands are much more extensive and with them comes a 100-foot buffer area," Yarrington said.

The original architects for RIT already built on the easiest areas for construction. Now, new development is limited to elevated lands on the south side of campus which are free from wetland restrictions and FEMA floodplain requirements. However, developing more facilities further from the main campus provides a transportation problem. Just simply laying down more asphalt for parking lots will have harsh environmental effects, so other strategies for transportation like busing and bicycling are encouraged for sustainability.

"If we want a high-energy, diverse, walkable campus, developing facilities far away from the center of campus doesn't reinforce that goal," Yarrington said.

Obstacles to expanding on protected wetlands encourages RIT to create spaces that have high density and diversity of usage. Yarrington provides Global Village as an example of a high density layout design: after parts of Riverknoll were demolished, Global Village was created to bring back some of the urban vibe of the former downtown campus.

"The Henrietta campus has 20,000 or so people there daily so it's like a small city," Yarrington said.

Whether the university will ever truly regain the cultural roots it left behind remains to be seen, but RIT is constantly evolving to be more innovative, diverse and inclusive in its ever-changing world.