Rochester is home to the most segregated school district border in the country, according to a 2020 EdBuild study. The city has been plagued by historical redlining and segregation, the effects of which can still be seen today.

Although our city has a rich history rooted in technology, photography and abolitionism, there exists a dark side to it that is often overlooked; and it’s not far from where we live.

Knowing and understanding the history of Rochester’s segregation is key to solving the contemporary issues that it faces. Problems such as gerrymandering — congressional district redrawing that often segregates — gentrification, food insecurity and poverty are all linked to the city’s history as much as its art and music.

What Is Redlining?

Redlining is a discriminatory practice that

Redlining in Rochester rose to relevance in the 1930s, when a map was drawn by the federal Home Owners' Loan Corporation to determine which areas would receive government insurance for home mortgage refinancing. The areas that obtained funding all had clauses in their property deeds that explicitly banned black people from owning the land.

Shane Wiegand, Rochester historian and fourth-grade teacher in Henrietta who co-leads the Anti-Racist Curriculum Project, explained the racial motivations that went into the drawing.

"Redlining has created a total disinvestment in homes across the city right whereas, in the suburbs, billions of federal dollars help build [the community] and invest in it," he said.

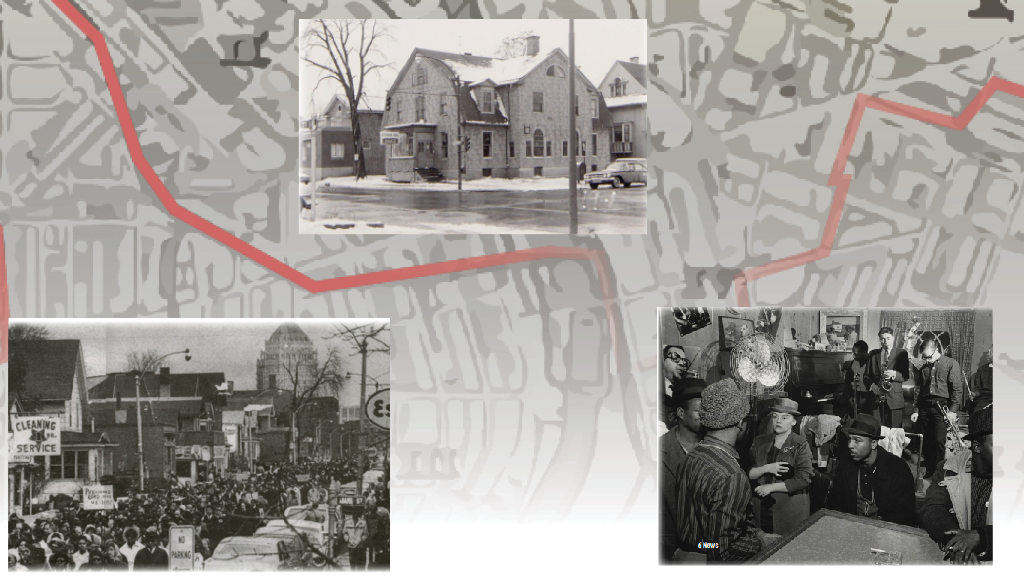

Wiegand superimposed the 1934 redlining map with a modern map of Rochester. Zones with a black population of 10 percent or over — like the 7th Ward — were labeled ‘hazardous.’ Today, many of Rochester's communities exist where they do because of prior redlining efforts.

By the 1950s, 80% of Rochester’s people of color lived in the third and seventh wards.

Sections of the city were designated as "racial covenants" for people of a specific color.

“The deed says no person of color can live there, enforceable until 1968,” Wiegand stated.

“The deed says no person of color can live there, enforceable until 1968."

Former RIT Presidents Royal Farnum and John Wegman both held properties that they willingly incorporated the clause into.

Judge Reuben Davis, a 19th Ward resident, recalled the primary effects of redlining efforts in relation to Rochester's suburbs.

“To my knowledge, there were very few persons of color living in the towns," he said.

Towns like Henrietta, Pittsford, Irondequoit, Webster, Gates and Greece were all mostly white-only neighborhoods at one point. According to a 2017 study by the Finger Lakes Health Systems Agency: a child from Pittsfords has a higher life expectancy than one from downtown Rochester. The difference stems from issues like food insecurity, poor air quality, as well as residents being unable to afford fixing outdated housing that was built with hazardous materials like asbestos.

Redlining and Education

The attitude permeated many areas of the city’s culture and leaked into the local educational system. Rochester’s white majority schools, segregated through the aforementioned redlining, annually held minstrel shows — live entertainment characterized by racist caricatures. Parents even had their children perform in blackface.

Black schools, on the other hand, faced funding issues due to redlining. The effects of it are still seen in the modern educational structure of Rochester city schools.

“When you look at the [Rochester] city school district, behavioral issues, the need for mental health professionals in schools; because of things like lead poisoning, the dramatic increase in poverty, all the different factors that are going on there,” Wiegand mentioned.

However, there is a reason why these problems have manifested.

“School funding is based on property taxes," Wiegand explained. "City property taxes are significantly lower because redlining has created a total disinvestment in homes across the city right whereas, in the suburbs, billions of federal dollars help build it and invest in it.”

"City property taxes are significantly lower because redlining has created a total disinvestment in homes across the city right whereas, in the suburbs, billions of federal dollars help build it and invest in it.”

Black people pursuing higher education in Rochester also faced issues in enrollment in certain programs, especially in the medical field.

The Voice, Rochester’s predominant black-owned newspaper at the time, tackled the issue. They reported on a case of George Whipple, the founder of the University of Rochester, who specifically defended and admitted to the practice of denying people of color admission to the university.

Edwin Robinson, the first black graduate of the University of Rochester’s Medical Center, was denied an internship at the Strong Memorial Hospital. The hospital had segregated maternity wards that were legally mandated.

A Local Impact

Redlining in Rochester not only created a split in the city’s neighborhoods but also led to the destruction of one of the city’s most vibrant communities, Clarissa Street.

According to the Corn Hill Neighbors Association, Clarissa Street was the commercial hub of the Third Ward. A church local to the neighborhood was “a center for the Underground Railroad, for Frederick Douglass’s abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, and for the women’s suffrage movement,” as noted on the association’s website.

Clarissa Street was once known as Rochester’s Broadway. The association also states that “Clarissa Street became famous for jazz and for clubs such as the Pythodd Club, the Elk’s Club and Dan’s Restaurant and Grill.”

The street was mainly destroyed by two factors, the first being the 1964 'Rochester Race Riots.' The riot, over police brutality among other issues of the time, destroyed much of the street and even included a helicopter crash that killed three people.

Clarissa Street was then slated to be a part of the city's Urban Renewal Program. The Inner Loop was built, cutting the street in half and separating it from the main street. The neighborhood exists today as a shell of its former self.

For more info on Clarissa Street, check out the documentary "Clarissa Uprooted."

Painful, but Not Forgotten