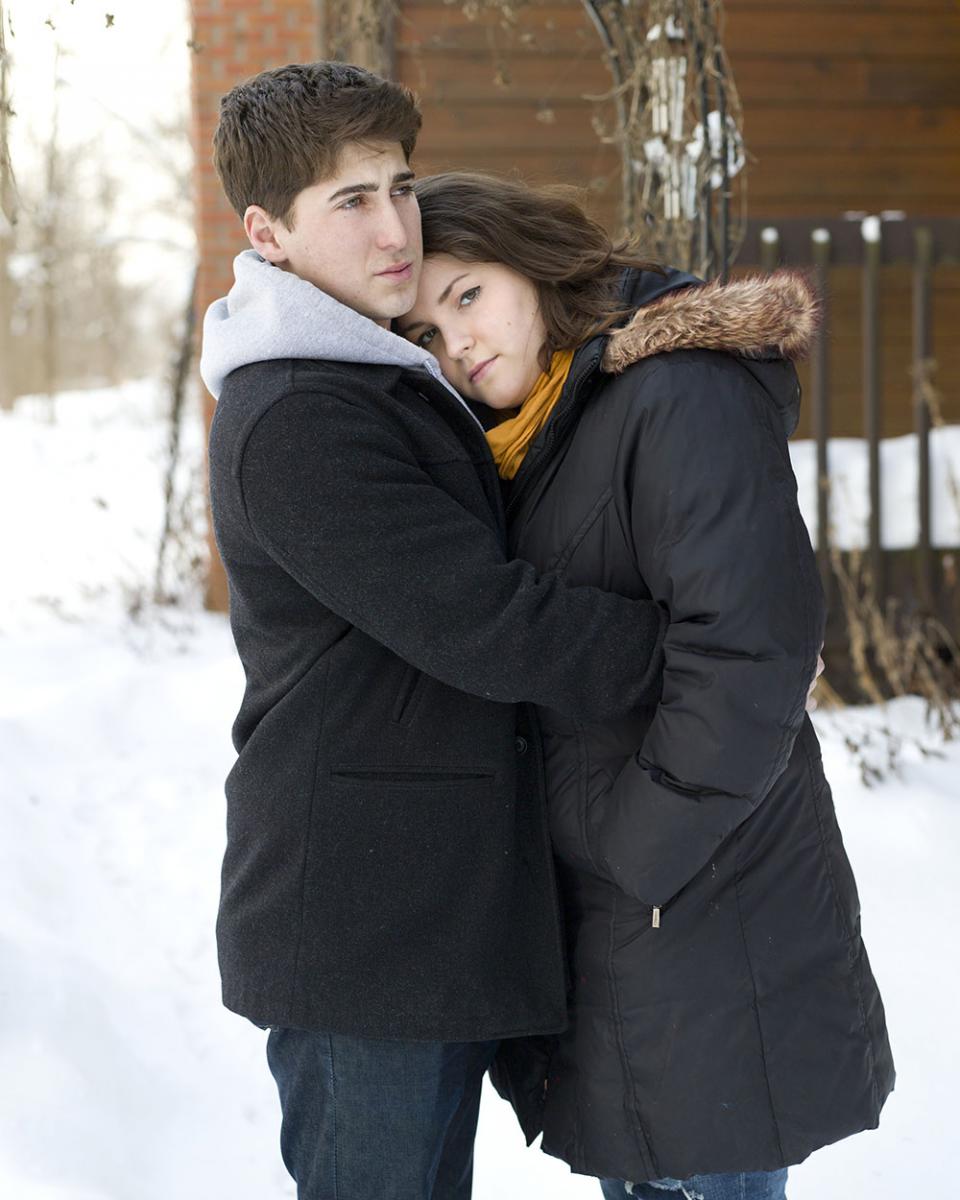

A young woman reflects on the effects rape has had, and will have, on her life. A man states that he will not let the experience change him for the worse. A seemingly innocent home of the clergy is described as a place of sexual assault. Rape can happen anywhere, anytime and to anyone, and that is what the photo project, Trigger Warning, hopes to convey to the Rochester community and beyond.

A young woman reflects on the effects rape has had, and will have, on her life. A man states that he will not let the experience change him for the worse. A seemingly innocent home of the clergy is described as a place of sexual assault. Rape can happen anywhere, anytime and to anyone, and that is what the photo project, Trigger Warning, hopes to convey to the Rochester community and beyond.

Lydia Billings, RIT Graduate in Fine Arts photography and creator of Trigger Warning, describers her project as a photographic exploration of rape and sexual assault. It began as a personal project to help her grapple with the questions what is rape, how does it affect people and when and where does rape happen? She started the project after the rape of her of best friend from high school.

“She was raped when she was 20, three and half years ago on her college campus,” said Lydia. “Until that point I did not have a clear understating of rape and how it affected people and their lives.” Since then, she has explored the effects of rape on individuals, communities and society.

Originally, she began the project with the idea of using police reports to find and photograph actual locations of where rape has occurred but due to the difficulty and lag time of getting the reports, Lydia met individuals on her own. As the project grew, she found people who were willing to share their own stories. She added their portraits and experiences to the project.

These stories and pictures are now on display in Rochester Brainery for the month of November. The gallery holds 11 portraits and 10 landscapes. The portraits depict various rape survivors who she asked to share their stories at whatever level of comfort they could. Those stories and many others are written in small books found next to some of the portraits on display.

These stories and pictures are now on display in Rochester Brainery for the month of November. The gallery holds 11 portraits and 10 landscapes. The portraits depict various rape survivors who she asked to share their stories at whatever level of comfort they could. Those stories and many others are written in small books found next to some of the portraits on display.

The gallery also depicts locations, ranging from homes to offices and forests, to show that, “Rape is not simply a dark alleyway sort of occurrence,” said Lydia. As stated on the project’s website, she hopes that the gallery can help incite conversations about rape, which is often a difficult topic to discuss or even acknowledge. Survivors should feel supported and comfortable enough to share their stories, while communities should be open enough to have these conversations. “A survivor can’t heal completely alone,” said Lydia. “The community should be directly involved in supporting its members.”

Lydia has seen people express a wide range of emotions while walking through the gallery exhibition. She hopes to create an impact and that the viewers of her project come out with a greater understanding and awareness of rape.

Lydia has seen people express a wide range of emotions while walking through the gallery exhibition. She hopes to create an impact and that the viewers of her project come out with a greater understanding and awareness of rape.

She said she does not feel attachment to any one image in particular, as they collectively share a larger idea. “I feel like a messenger. I’m proud of the images because I’m proud of the people in them,” said Lydia. “I’m proud of the fact that they are able to share their stories at this point in their lives.”

Stories and Faces

Story: A 28-year-old bartender took her usual walking route home one late night after work. She had never experienced or heard of violence in the neighborhood, but crossed the street when she sensed someone following her. About two blocks later, the stranger had caught up and grabbed her by the wrist. She struggled, but he forced her into the driveway between two homes. After raping her, he left her on the street. She stumbled the remaining half-block to her apartment and called the police.

Face 2: In 1988, she reported her assault to the police. When she told the officer that her rapist was her husband, he asked, "Why are you wasting my time?" and refused to pursue the report.

Face 3: Rorie, assaulted April 2010 on her college campus. Rapist found "not responsible" by her university's judicial system.