It’s late and you begin to feel that familiar pain in your stomach — suddenly the only thing on your mind is the batch of cupcakes in your kitchen you have left over from the night before. You ask your friend if she wants anything, and she responds with a question thatmakes you realize just how little you actually know your best friend:

"Can I have one of those muffins?"

The hunger turns to rage and a heated debate begins. A cupcake isn't the same thing as a muffin, is it? One question becomes a string of other controversial topics. Does pineapple belong on pizza? Is a hot dog a sandwich?

There’s a reason why we don’t have a definitive answer to any one of these questions — they are all based on opinion. The only one who can answer these questions is the person asking them, but that doesn’t stop us from debating them.

Why Do We Care?

Take a look around whatever room you’re in. Notice each of the things in the room, but don’t put those objects in a group. Instead, look at the individual title of a book, the name of the snack on the table or the material and color of the vase in the corner and treat them as unique objects unlike any other in the room.

Unless you’re in an empty, windowless cell, you can likely see hundreds of different things around. It can be overwhelming to look at each of these items one by one, so humans decided that it would be easier to group them together.

With this mindset, now the room that you’re in could have books, desks and computers. It’s much easier to wrap your mind around a few different groups rather than hundreds of individual items.

William Middleton, a professor of sociology and anthropology with a focus in cultural food studies, gave his understanding of why it's easier to look at items while they're in categories.

“Humans are really good at classifying things, and I think it’s vital for our existence to be able to lump certain seemingly familiar concepts together,” Middleton said.

"It’s vital for our existence to be able to lump certain seemingly familiar concepts together."

Not only does classifying different objects make viewing the world a little more bearable, but it also allows us to form an opinion on something previously unknown because it shares characteristics with something else. For example, if you see a mosquito, it is easily recognizable as a bug. In your mind, if all bugs are gross, the mosquito will be, too.

Anthony Jimenez, a professor of sociology and anthropology, explained why we might use categorization as often as we do.

“From a sociological perspective, categorization has to do with meaning making; I think that, as human beings, we like to categorize things because we’ve internalized meanings associated with those categories," Jimenez said. "We like to do that because they make sense to us and they correspond to messages that we’ve been taught from our childhoods and onward.”

So if categorization can help us manage our day-to-day lives and give meaning to seemingly unimportant objects, does it really matter if it causes an argument every once in a while? As it turns out, trying to fit things into specific groups might be doing just as much harm as it does good.

Dangers of Dichotomies

Categorization branches beyond simple food controversies. You might not hurt anyone if you try to label a hot dog a sandwich, but what happens when it doesn’t stop there — what if you try to put a label on everything you know?

“The problem [with categorization] is this; sometimes we’re too good at spotting these patterns of similarity," Middleton said. "In pathological cases, you get conspiracy theories — where everything has meaning and everything is signifying something else."

"Sometimes we’re too good at spotting these patterns of similarity."

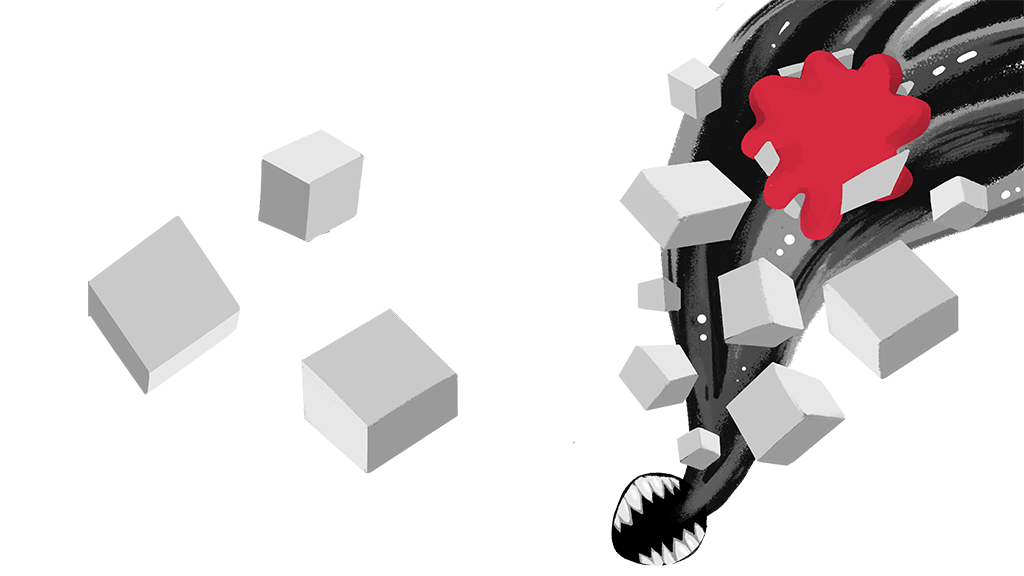

Not every object or situation in life has meaning beyond its surface level. When we try to find a meaning that didn't initially exist, it's easy to fall down a rabbit hole of conspiracies.

Beyond conspiracy theories, another issue with categorization is that it tends to work in dichotomous pairs. Often, a question will be framed with choices like “this or that.” Such a dichotomous question can lead people to believe that the answer is black or white, but more often, the answer falls somewhere in the gray area.

Jimenez maintains that generally, dichotomies can cause problems or even loss of perspectives. A Brain Food article titled “This or That: How Useful Are Dichotomies Really?” discusses the same concept.

“Things are often more complicated than just a ‘one or the other’ scenario. Happiness and sadness exist on a spectrum, much like light and all its different shades and hues. The simplistic way of categorizing this information doesn’t always capture the whole picture,” John Panetti, the author of Brain Food, wrote.

Asking a question itself isn’t harmful, but asking a question designed to have only two answers can discredit other opinions someone may have on the topic.

Thinking Differently

You might still be upset that your friend suggested putting pineapple on pizza, and that’s your prerogative — but keep in mind, they might consider your favorite toppings weird, too. Everybody comes from a variety of different backgrounds that socialized them into knowing what they now consider to be normal.

Sure, these dichotomies might not be harmful when asking a question like “Coke or Pepsi?” but they can be when discussing more serious topics, such as gender, law or politics.

Like puzzle pieces, not everything you know is going to fit into one specific category. What's the point in trying to shove the pieces into a puzzle where they don’t belong? So go ahead — put the pineapple on the pizza, dip the fry into the milkshake and call the hot dog a sandwich. Until there is a definitive answer to those questions, you can’t be wrong.