"We're trying to figure out how skills can transcend just 'nice things.' We want to push boundaries," said glass professor David Schnuckel, echoing the thoughts of many in RIT's School for American Crafts. While the SAC may be a small faction within the broader College of Imaging Arts and Sciences, the department is constantly asking what's next — whether that means a ceramic 3D printer or a partnership with a leading institute of glass research.

3D Printing and the Future of Ceramics

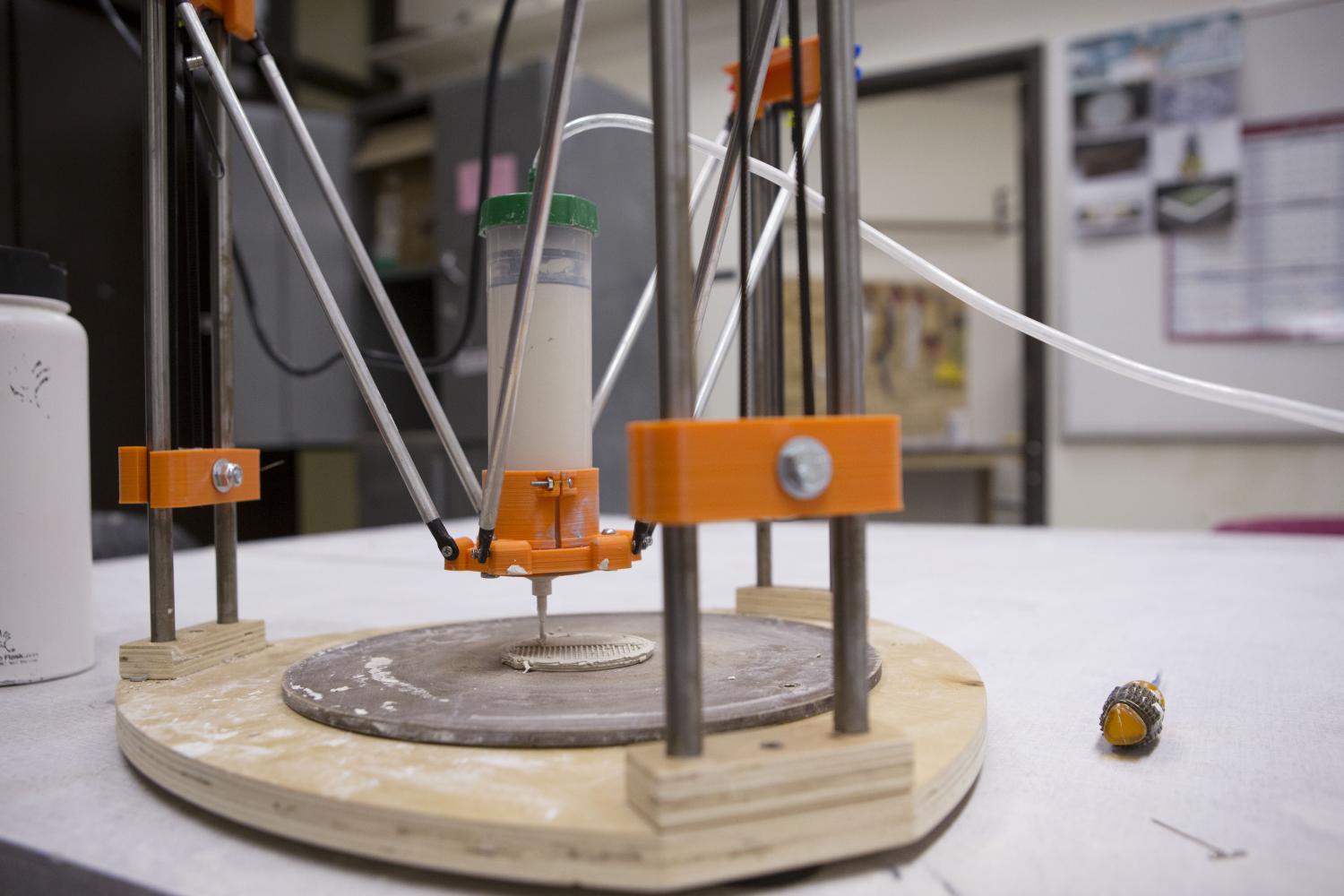

In the third week of February, Bryan Czibesz, ceramics professor at SUNY New Paltz, came to campus for a couple days to facilitate the installation of RIT’s first ceramic 3D printer. In just three short hours, the RIT ceramics department built and programmed their very own printer under his guidance.

Like most 3D printers, the ceramic printer now located in Booth operates via Computer-Aided Design (CAD) files. After the machine is programmed, wet, loose clay is pumped through an apparatus that travels in concentric loops to build up material. The final results are fascinating, other-worldly constructions.

Czibesz, who has built a staggering 40 ceramic printers and led countless workshops, was especially impressed by the tenacity and creativity of RIT students in the ceramic program.

“That why I love doing these workshops,” said Czibesz. “I love the contact, the ideas that come and are generated by the presences of people thinking about this machine that can be so abstract.”

“That why I love doing these workshops,” said Czibesz. “I love the contact, the ideas that come and are generated by the presences of people thinking about this machine that can be so abstract.”

“As soon as someone sees something in motion, it reminds them of things,” he went on to elaborate. “As soon as people see the potential of forms, the potential of the language of the machine — things occur. This is the way new things come. Not all great ideas come out of vacuum — very few do.”

Not only did Czibesz and the students experiment with the capabilities of the machine, but they also engaged in a dialogue over its ramifications. One of the main points of discussion revolved around the future possibilities of 3D printing technology.

“I’m interested in the digital as an emergent material. I think it’s a thing we kind of haven’t sorted out yet,” said Czibesz. “I don’t think we really understand what’s happening with our ability to simulate things on a computer.”

Nevertheless, the thought of the unknown is what Czibesz finds most intriguing. “I have some ideas of what the outcomes might be, but I find even from just moment to moment the results are not what I anticipated,” he said. “And if you extrapolate that into the future, I guess that I am slightly reassured that it will continue to be interesting because we don’t really know what is coming.”

Another source of debate focused on the contradiction between ceramic’s lengthy history and 3D printing’s relatively short one. “I think there is also this tendency to label ceramist as ‘luddites’ or people who don’t embrace technology — but that’s not true,” said Czibesz. “Clay is a really sophisticated and nuanced material technology. But, digital is a new one. And I like how 3D technology kind of bridges the gap, that it’s just one next step on the continuum of making things.”

In some ways, however, 3D printing technology modifies an essential hallmark of ceramics —its intensely tactile nature.

“There’s a group in Nebraska called Tethon3D that is experimenting with ceramic powder and resin 3D printers,” Czibesz described. “One of the benefits of working that way is that the resolution can be finer, the clarity and quality of the objects is closer to the digital version. However, the disadvantage is there’s no hands-on element at all. You take it out of the machine and it’s done, really.”

In order to combat that in his own work, Czibesz manipulates his pieces both during the printing process and after. “I try to print them in such a way that’s really hands-on, physical,” he explained. “The structure is really tenuous, the manipulation needs to happen in order to keep it standing up, I’ve been making additions to it while it’s building ... So, it’s something that I can micromanage on the printer as it’s happening. I like that I can tinker with it.”

While Czibesz has developed his own 3D printing methodology, members of the RIT ceramic department can now decide how they want to utilize their machine. They get to choose whether they want to focus on its precision, zoom-in on its ability to create novel forms or leverage its contradictions.

“This room full of people built it,” said Czibesz. “They now have enough knowledge of how to use it. And that’s empowering, it’s democratizing.”

“This room is full of people built it,” said Czibesz. “They now have enough knowledge of how to use it. And that’s empowering, it’s democratizing.”

RIT Glass' Groundbreaking Partnership

Several very exciting developments are also occurring just up the stairs from the ceramic 3D printer, in RIT’s glass studio. Just this past month, the program formed a partnership with a local giant in the industry: the Corning Museum of Glass.

“We’re interested in forming an alliance with Corning to better inform our students about what they’re actually engaging in studio, how that fits into the rich history of this material, and how it fits within the contemporary context of glass,” explained glass professor David Schnuckel.

The partnership was also formed to ensure that RIT glass stayed current with industry trends. “Material exploration seems much more of interest in the field in terms of what people are doing in their studio practice,” said Schnuckel. “You see this interesting kind of balance of people who are doing this to make a living, and the people who are changing the game in terms of what is possible, what glass is all about, by testing experimental avenues.”

Because glass is a material unlike any other, Schnuckel believes that having a fundamental understanding of its properties is necessary.

“It’s essentially made up of materials of the earth — sand, limestone, ash — they’re just raw ingredients that get freaking hot,” he said, laughing. “And then they create this really strange glass body that we’ve all come to know in various ways with our day-to-day interactions. So we need to talk about what characteristics are unique to glass, as a material, that we may

With all of this in mind, the RIT glass program plans on working intensely with Corning’s chief scientist, Dr. Jane Cook, for the foreseeable future. Although the partnership has just come to fruition, the department has already hosted Cook on campus and traveled down to Corning for a tour of the facilities. Soon, the two programs intend on collaborating on a project that is still currently in the works.

Given the promising direction the relationship already seems to be heading, Schnuckel is optimistic about the possible educational avenues his students will get the chance to explore in the years ahead.

“Just scholastically speaking, using Corning as a resource will be great,” he said. “They even have a glass-based library — anything involving glass, they’ve got it, from recent exhibition catalogs to Renaissance-era Murano manuscripts.”

“Professionally, with our students, they’re a really great resource to have in terms of what they may or may not do once they graduate,” explained Schnuckel. “We have had students find employment opportunities through them in a variety of ways. Whether it’s curatorial, educational or whether its based in art or entertainment.”

Embracing Technology in Innovative Ways

Before the students emerge into that professional world, however, Schnuckel and his fellow faculty members have made it their goal to ensure their pupils are getting truly a world-class education during their time at RIT.

“Our job has not only been to maintain our program — we may be small, but we have an international reputation,” Schnuckel explained. “So we have to find ways not only to maintain that legacy, but also to ask, 'In what ways I can enhance it, expand upon it?'”

In recent years, that expansion has meant many things — including an update in facilities. Just like the ceramic studio downstairs, the glass program is also starting to incorporate more cutting-edge tools into their curriculum.

"What we are trying to do is facilitate this integration of technology into what has traditionally been such a tactile, hands-on field."

“What we are trying to do is facilitate this integration of technology into what has traditionally been such a tactile, hands-on field. For example, on this side of the room are our beginnings of a digital fab lab,” said Schnuckel, gesturing to a side of the studio complete with glistening, brand-new machinery.

Alongside the new tools, the program has started to incorporate recent video technology as an instructional aid as well.

“Glass processes ask a lot from us in terms of how we use our body, how we use tools as extension of our bodies,” Schnuckel said. “For instance, I can go in the hot shop and demonstrate the proper way of what’s called a 'punte.' Now, I can film that so the students have a visual resource. But then what I can do is film a student making a punte, and play those two things side by side. I can show them what’s different about theirs from mine using a motion analysis app.”

Not only has the program started to incorporate video as an educational tool, but some of its members have also started to explore digital media as a form of artist expression.

“There are time-based forms of technology that don’t have anything to do with the physical manufacturing of glass. Things like video, projection,” explained Schnuckel. “In fact, for one of our current grads right now, his whole thesis is on looking for this harmonious relationship between the projected image and glass as the hosting canvas.”

"We're asking ourselves a lot of questions — what kind of relationships can we create, either metaphorically or otherwise? Artistically? Conceptually?” Schnuckel continued. “It’s just a fascinating time.”

“We’re asking ourselves a lot of questions — what kind of relationships can we create, either metaphorically or otherwise? Artistically? Conceptually?” Schnuckel continued. “It’s just a fascinating time.”

Although clay and glass are two artistic mediums that have millennia-long histories, the departments here at RIT strive to engage with their respective materials in new and inventive ways. Much like the rest of the university, their willingness to embrace innovation has the programs for success — and guarantees that they will continue to move forward in ways we have yet to even imagine.