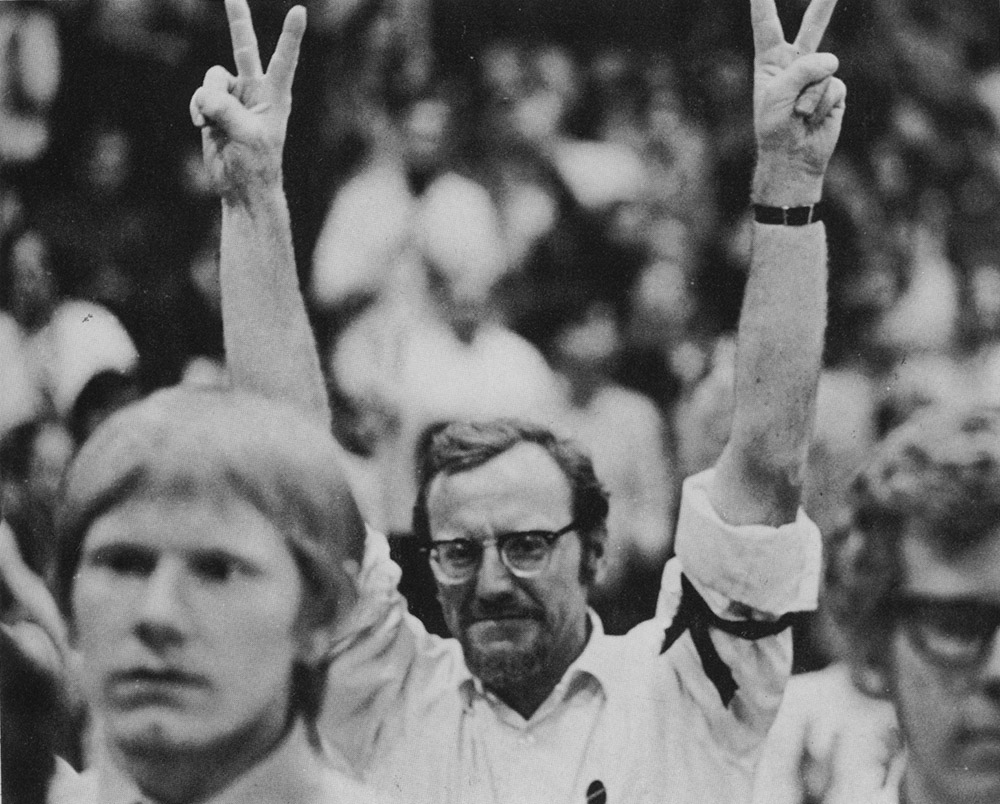

The Vietnam Moratorium Committee staged what is believed to be the largest anti-war protest in United States history 50 years ago on Nov. 15, 1969. Nearly half a million citizens attended the largely peaceful protest, including politicians and musicians.

While smaller than many modern-day protests, the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam and other protests like it were some of the first of their kind. They helped usher in a new era of dynamic protests that are spurred on by free speech, more direct news reporting and youth engagement.

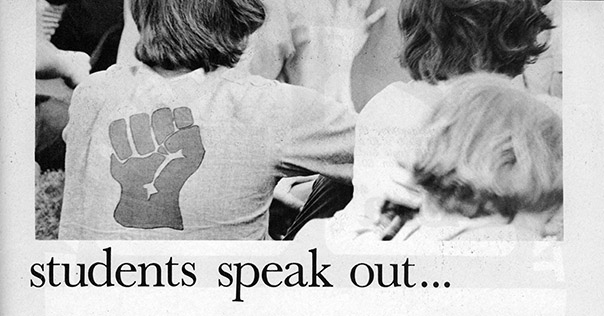

One of the more defining aspects of the anti-war movement were the protests on college campuses, incentivized by the ever-increasing aggression of the army draft. Protesters on college campuses were frequently the first and loudest voices to speak out, even when the vast majority of the American population still supported the war.

The Center of a Movement

Campuses all across the country were hotbeds for anti-war activism. Tamar Carroll — an associate professor of history, specializing in U.S. history from 1945 to the present — explained some of the context.

“It started in Harvard University, it’s an outgrowth of McCarthy-era suppression of labor unions and left-leaning activists in general when people were being purged from the U.S. government,” she said. “A film that showed an HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) committee meeting was shown at Harvard University, and students felt that [what] the film depicted was contrary to democracy as they understood it.”

Carroll suggested this was where students began protesting the Cold War, and where the activism of the New Left, a new form of student social activism, first originated. Later, the University of California Berkeley would help create the Free Speech Movement and protest for other causes alongside those who participated in the 1960 HUAC protest. It was from this early activism for free speech that protests arose in the Vietnam era.

During thise Vietnam era, students on campuses across the country participated in the protest, including some from RIT. While infrequent in the beginning, Reporter began to cover the divisive topic; Neil Shapiro, a column writer at Reporter during this time, covered anti-war activities on campus.

"I was at Reporter all four years, from freshman through senior [year],” he said. “I started just writing for the magazine, then I was the editor in chief.”

Having experienced it, Shapiro said that students' initial reactions were ones of support toward the war, but mentioned that this outlook would change as the war did. There were few who had any real idea why America was involved in the first place, or what it would cost. As these truths emerged, support shifted.

“When the country goes to war, there is a great deal of support — at least at the beginning,” Shapiro said. “[Then] it became clearer and clearer that nobody knew ... why we were over there.”

"When the country goes to war, there is a great deal of support — at least at the beginning."

As the war dragged on, more students became involved in the war through enlistment or the draft. It was stated in the January 1969 Reporter magazine that draftees went from 4 percent college graduates to 90 percent. They would return home with terrible stories — if they came home at all. As Shapiro stated, this support turned into tremendous protest.

Unlike UC Berkeley or Harvard, RIT staged no major protests and was a relatively quiet campus with only a few marches against the war, according to Shapiro. Only a few small organizations known for anti-war activism tried to gain membership.

“The Students for a Democratic Society [a major anti-war organization] tried to get a presence at RIT, very few people were really interested in it,” he said.

The administration also engaged in protests, permitting students to take final exams early if they wanted to participate in the protests.

Reporting the War

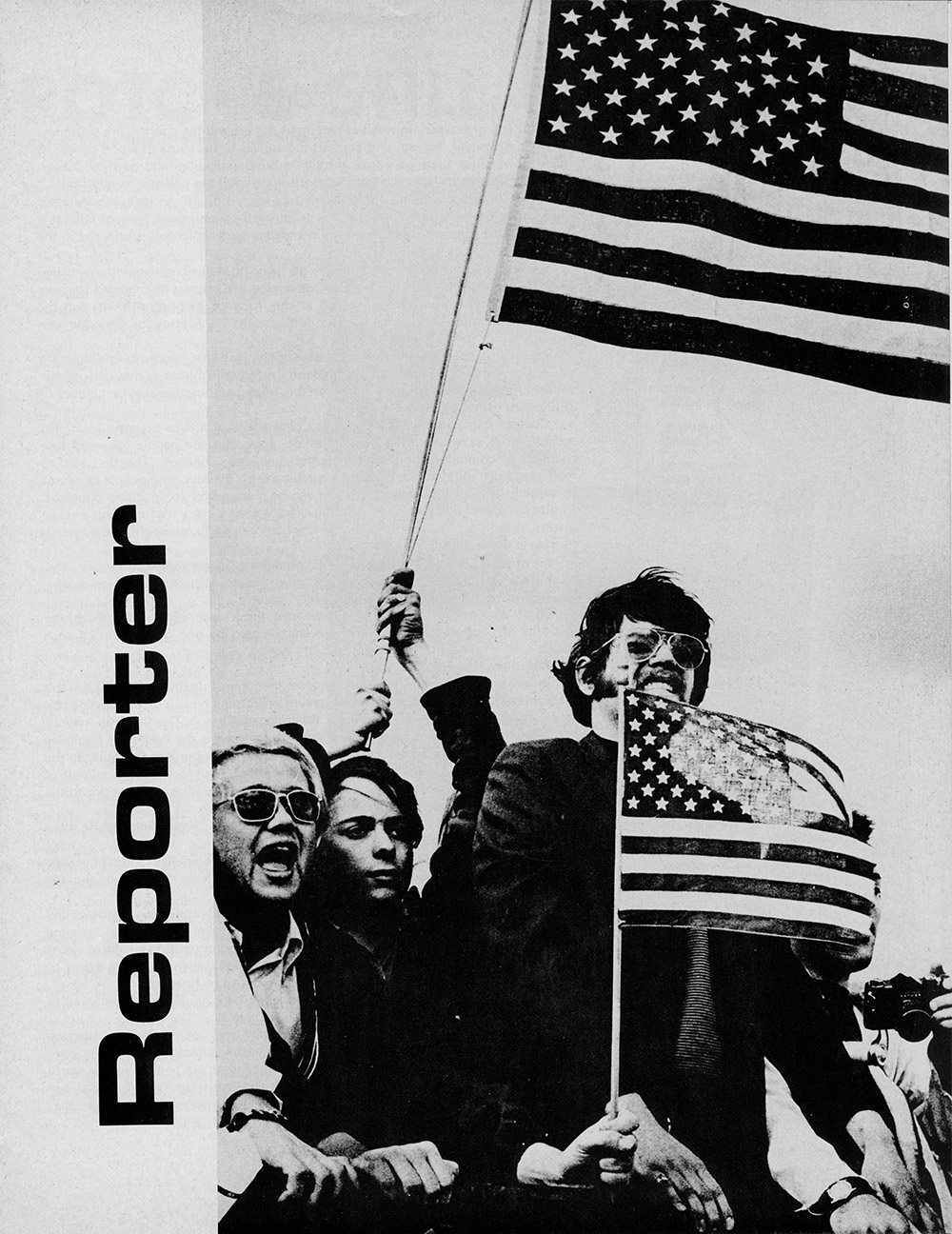

Reporter covered several anti-war activities over the years, starting in one of the earliest recorded weekly magazines.

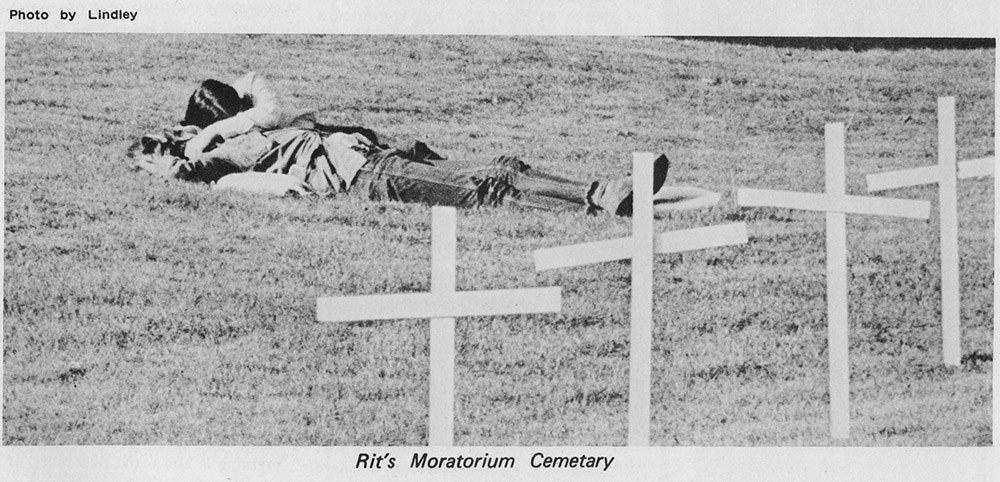

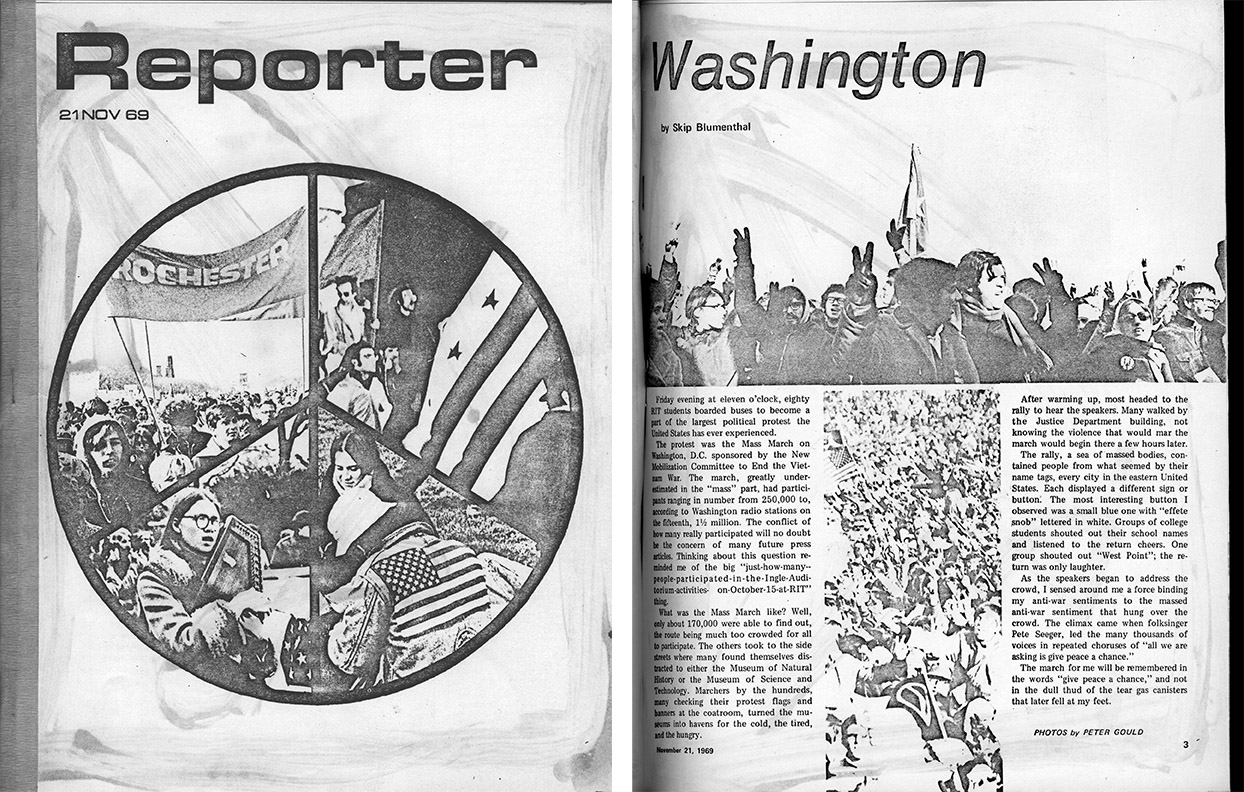

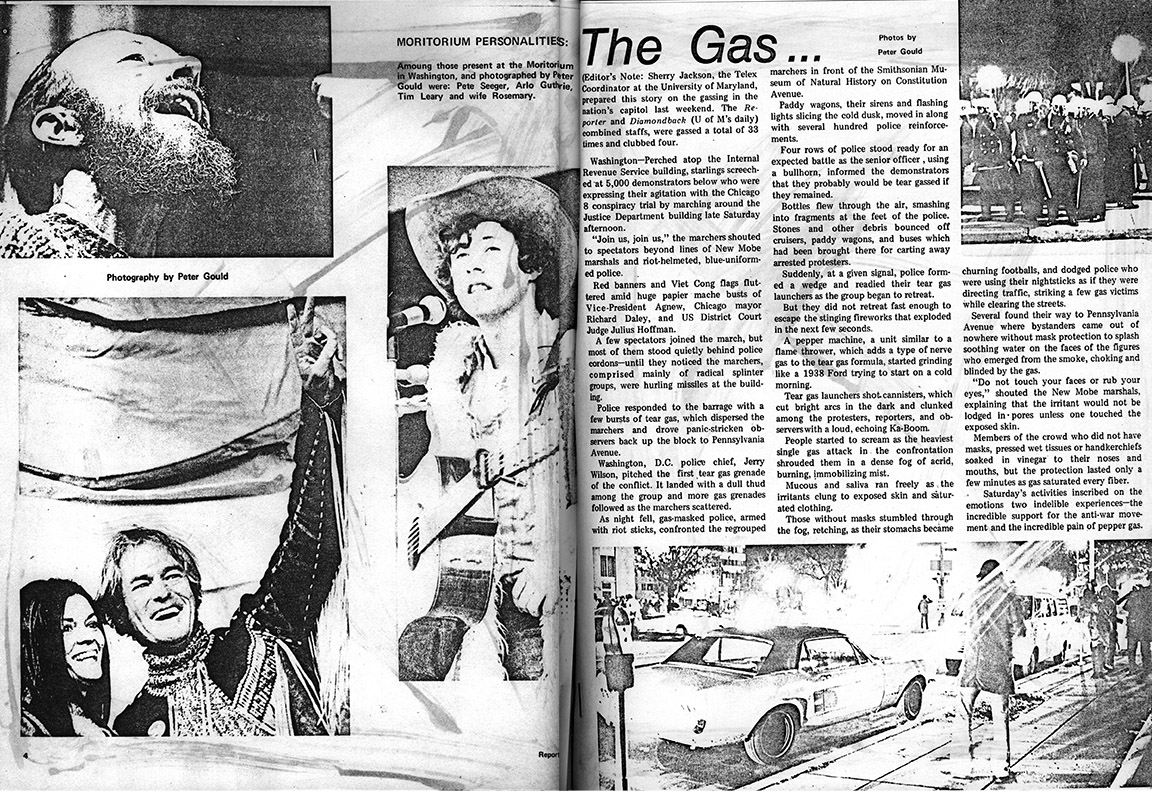

These included the introduction of ROTC to RIT's campus in February 1969 and the plan brought forth by Reporter editor Bob Kiger in an April 1969 edition titled "Five Months to End the War," which was adapted by a national committee and made into a nationwide Moratorium to be held on Nov. 15, 1969. Reporter also covered the March on Washington protest, attended by 80 RIT students, which would become the largest anti-war protest in U.S. history at the time.

Wonder Woman Meets GI Joe

Despite future coverage, Reporter was somewhat absent from early protests.

“One of the main complaints was that Reporter never did anti-war stuff and never gave a voice to the other side,” Shapiro said.

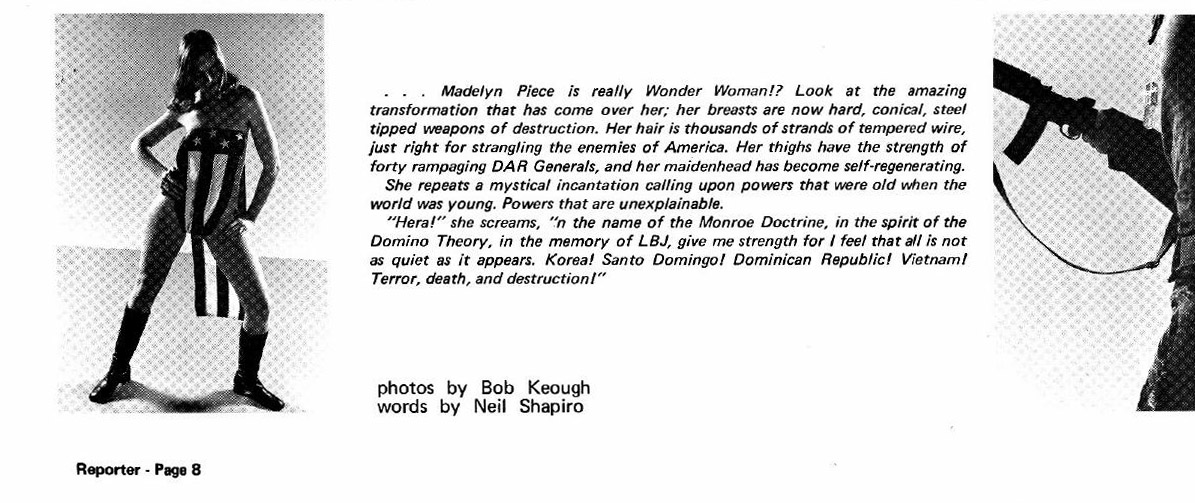

However, that was about to change. According to Shapiro, RIT had always been a conservative campus. When a conservative photography professor was accused of grading a student negatively in part because the student was anti-war, the professor set out to prove a point.

“He basically replied, ‘Well, you know what, I could take better anti-war pictures than you if I wanted to because I’ve got talent and I know technique,’” Shapiro recited.

The professor, Robert Keough, took said images to Reporter where Shapiro was directed to write a story on it. This article became known as “Wonder Woman Meets GI Joe,” and was published in the April 4, 1969 issue as the first part of a satire against the war.

The second part of the installation was published on April 25, 1969. Later that night, Shapiro, Keough and then-Editor in Chief Robert Kiger were arrested by state police.

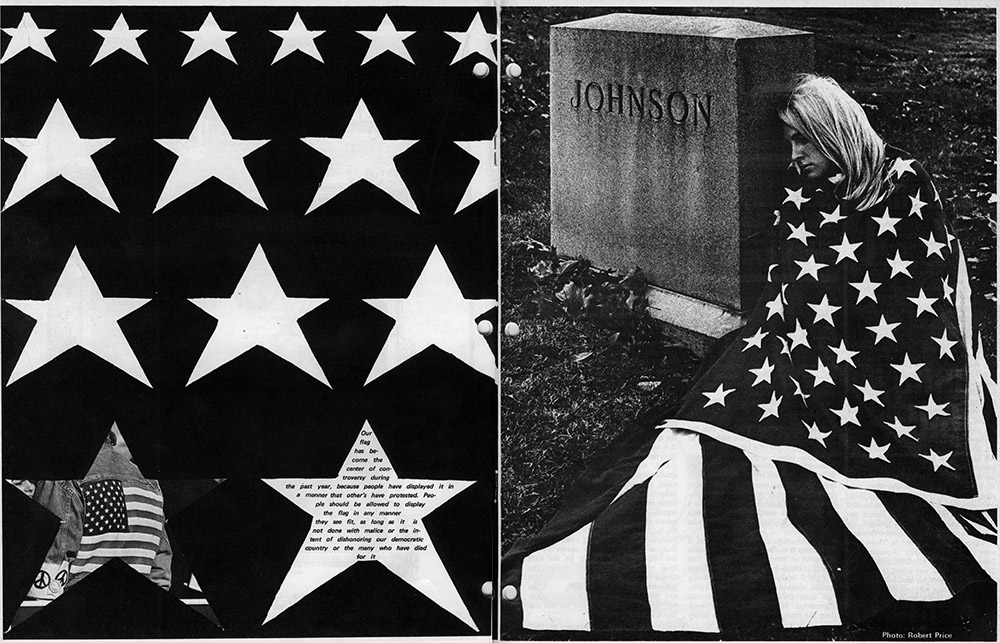

“People who didn’t like the article went to the justice of the peace court and pressed charges against the university and Reporter about desecrating the flag,” Shapiro said.

The reasoning behind the arrests related to an obscure section of New York state business law that kept the flag from being desecrated. The article showed the photographs of a woman draped in the American flag and little else standing behind a man dressed in a marine outfit. To three RIT students, this choice of apparel constituted desecration, and they reported it to the authorities. In less than a week, the two models included in the photographs were also arrested.

"People who didn’t like the article ... pressed charges against the university and Reporter about desecrating the flag."

After being found guilty, the group was ordered to write an apology to the city through the Times Union, which they never wrote. Despite this ruling, their lawyer, Julius Michaels, petitioned the case to the NYS supreme court.

“He asked that the ruling be overturned, and he based it on the freedom of the press amendment and various other things,” Shapiro explained. “It wasn’t until a year after I graduated from RIT that it was totally overturned … the New York state supreme court ruled in favor of freedom of the press.”

While they were only held in jail for two hours, the actions created a tense conflict between the RIT administration, the student body and Reporter.

"The RIT administration started off not being very supportive,” Shapiro said. “They shut off publication of Reporter magazine for a week.”

Rather than halt publication, an understaffed Reporter published their next magazine with a blank cover. Facing an ongoing battle with the administration, many of Reporter's staff simply resigned. Eventually, once the case was finally resolved, the administration became more supportive and the staff were reinstated.

Then and Now

Protesting in America, both on campus and off, has changed dramatically. One difference, as stated by Carroll, is the lack of youth activism.

“There’s no draft, so students aren’t worried about being drafted themselves," she said. "So we don’t see the same level of youth activism as we did in the Vietnam era.”

Shapiro agreed, saying to keep in mind that people were being picked in a lottery to go to war, being yanked out of their lives with only some returning. While this loss of life was very apparent during the latter parts of the war, we don't see the gruesome reality as much now; civilians aren't as exposed to the graphic images, body bags and other direct impacts.

“People have been desensitized because of the lack of news. The lack of news coverage in Vietnam was tremendously different than the news coverage we see now,” Shapiro said.

According to Shapiro, the hopelessness and loss of life was more apparent, as it was a regular occurrence to lose a friend. With this desensitization, and even before it, there is complacency that comes with detachment. Sometimes, this apathy can even turn hostile.

“When Susan B. Anthony protested, she had a lot of bad things thrown her way,” Carroll stated. “Protesting by its nature is controversial; not everyone appreciates it.”

“Protesting by its nature is controversial; not everyone appreciates it.”

Carroll believes that in the coming years, there will be more attention paid to current events like climate change and, when they look back, people will recognize these protesting individuals were on the right side of history — much like major movements of the past.

Political Divide

While many students tend to be apathetic toward certain events, there are just as many that take firm opposing sides in an ever-increasing divide that is only getting worse. In this way, protests haven’t changed much.

According to Shapiro, things only became more divided as time went on. Most students, detached from the war, could not rationally form an opinion on the conflict. This lack of information was easily abused by those in power.

“The leaders [of the organizations] worked solely for their own ideals without any real attempt to make the issue clearer to their followers but simply use their followers to further their own ends," Shapiro said.

Shapiro saw the Vietnam War turn Americans against each other. In the beginning, many were directly opposed to the soldiers that were fighting in the war, rather than the administration sending them. It wasn’t until soldiers began to return and tell their stories that he saw people recognize soldiers for who they were and turned their anger away from fellow Americans and onto the government instead. While he recognized that we are not opposed to soldiers in more modern protests and that we learned good lessons during the Vietnam protests, we have also never been more divided in modern times.

“One of the main problems we had in the ’60s is people only talked a lot on each side to each other and drummed up emotions,” Shapiro explained.

However, even over 50 years later, Shapiro still sees these same issues. Today, he attributes this to social media.

“They only showcase the opinions of the worst of the people who have opinions,” Shapiro said.

Shapiro just wants to see students spending time talking to each other, regardless of the issue or the side that they are on. As he stated, in the end, we’re all Americans in this together.

While the nature of protests and the manner in which they are covered has changed over the years, there are a surprising number of similarities between then and now, and lessons we still haven’t learned. When it comes down to it, protesting shouldn’t devolve into what the protest was likely about in the first place: hatred for others.

Ultimately, Shapiro implored that “students today need to reach out — I don’t care what side of the issue they’re on — and try and find what the real issues are, not what some jerk says they are, and discuss these things and decide what the best is for you."

Note from the Editor: Article has been updated as of Nov. 5, 2019 to clarify that the Free Speech Movement preceded the anti-war movement and that some of those featured in the 1960 HUAC protest would later become active in the Free Speech Movement.