The novel coronavirus pandemic has had a noted impact on many. Across the world, public areas shut down, with the future uncertain. It’s been said that these are unprecedented times; but despite the uncertainty, RIT has been constantly adapting to protect their community.

“The number one thing we’re concerned about is the health and the safety of our community and of the world at large, and so a lot of our decisions are based on that,” said RIT President David Munson.

Munson and others have been constantly working throughout this crisis to determine solutions and stopgaps that prevent the endangerment of those on and around campus, as well as their family members.

The Start of the Virus

The virus was first reported in Wuhan, China, and was linked to a local seafood market. While some criticize these findings, and argue the virus may have originated elsewhere, it is clear that the virus first spread widely within Wuhan and, later, greater China.

RIT operates a campus in Weihai, China — 650 miles from Wuhan. Therefore, the university was one of the first in America to begin seriously monitoring the virus, out of sheer necessity.

As the virus spread throughout China, RIT worked with Chinese officials in early January 2020 to transition to online course instruction, according to Sandra Johnson, senior vice president of Student Affairs.

Early Warnings

Email communications were sent throughout the early Spring semester, and greatly increased in frequency by March.

On January 24, 2020, the Student Health Center sent an email regarding an “influenza-like” illness. No one, however, expected a pandemic to follow.

Additional statements were released on January 29 and February 28.

Munson released a statement on March 5 urging caution while traveling during spring break — his first major communication of the crisis. The following day, Provost Ellen Granberg sent an email to faculty advising they prepare an alternative method of instruction for their courses.

“If a significant disruption occurs, it may come with little notice. For this reason, we are starting immediately to ensure resources will be in place if they are needed,” the statement read.

“If a significant disruption occurs, it may come with little notice."

Five days later, on March 11, Munson officially announced the transition to alternative course delivery.

Difficult Decisions

Along the way, many decisions were made to protect students both on and off campus.

“As it became more apparent that this was a worldwide issue ... we pulled our students from our study abroad program in Italy [and other locations],” explained Johnson.

She continued by saying, “The first operational change — the decision to move to alternative methods of course administration — was made in early March. And that required the extension of the spring break period in order to prepare for that.”

These decisions were not made lightly, and Munson expressed his understanding of the hardships that would befall students and faculty alike with this change.

“In the early days of the situation, we were hoping ... that we could still have students on campus who were heavily engaged in the studio arts, students who were working on project teams [and] students who have very heavy laboratory schedules as part of their curriculum,” he said.

“We know all of that hands-on project kind of work is harder — and in some cases even impossible — online; and so we were hoping to maintain some of that kind of activity,” Munson explained further.

Students have expressed frustration with the lack of access to equipment, software, tools and even ongoing experiments left on campus. Administrators seem to fully understand and share in this frustration. They too, wish for students to be able to access everything they need on campus.

“In the current situation that’s just not possible,” Munson continued. “And we all get it, and we all understand. [But] it’s just not really safe to have people in close proximity to one another right now.”

Munson and Johnson were not alone in making these tough decisions. RIT has long had a team in place to deal with potential crises. The Critical Incident Management Team, as it is called, is headed by John Zink, the associate vice president of Global Risk Management. The team is further comprised of other key figures.

“There are representatives from across the university — Academic Affairs, Facilities, Student Affairs, Dining, Marketing and Communications — pretty much all of the divisions that have significant roles in operating the university,” Johnson said.

This team undergoes regular training to deal with any crisis that may arise. RIT largely owes credit to this team for the quick response of the university, and they in turn have their training and precedents to thank.

Bob Finnerty, associate vice president of University Communications and the Chief Communications Officer for RIT, is a member of that team. He cited RIT’s responses to previous outbreaks, including the 2009 outbreak of swine flu (or H1N1) as well as the Avian Flu. Additionally, he recounted a coincidental training session held over the summer.

“Last summer I recall being at a training session down in Public Safety and we must’ve had 50 people from across the university,” he said. “The issue was a pandemic occurrence.”

Plans were in place for a situation such as this and, coupled with a heavy amount of resources available to RIT and other universities, the path forward wasn’t as hazy as one might expect.

“You can’t plan for everything — and certainly this one has taken a lot of twists — but it’s amazing that in the United States there is a playbook [and] everyone from RIT to Henrietta Ambulance to Monroe County Health Department all the way up to the [national government] has the same playbook,” Finnerty said.

The Resources Used

The “playbook” Finnerty referenced is a program hosted by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The FEMA program, Emergency Planning for Higher Education Training, ensures that university leaders receive training and certifications dedicated to the protection of a university and its inhabitants during an emergency, such as a natural disaster or terrorism incident.

Through this program, universities such as RIT have access to the same information that medical personnel have at all levels of government, from federal to local. That includes medical briefings, organizational charts, flowcharts and preferred vocabulary to ensure everyone is communicating in the same manner.

During a crisis situation, having a common basis for all parties across the nation to work from is immensely valuable. It ensures everyone is getting consistent updates and that no state, community or university is left behind in the sharing of information.

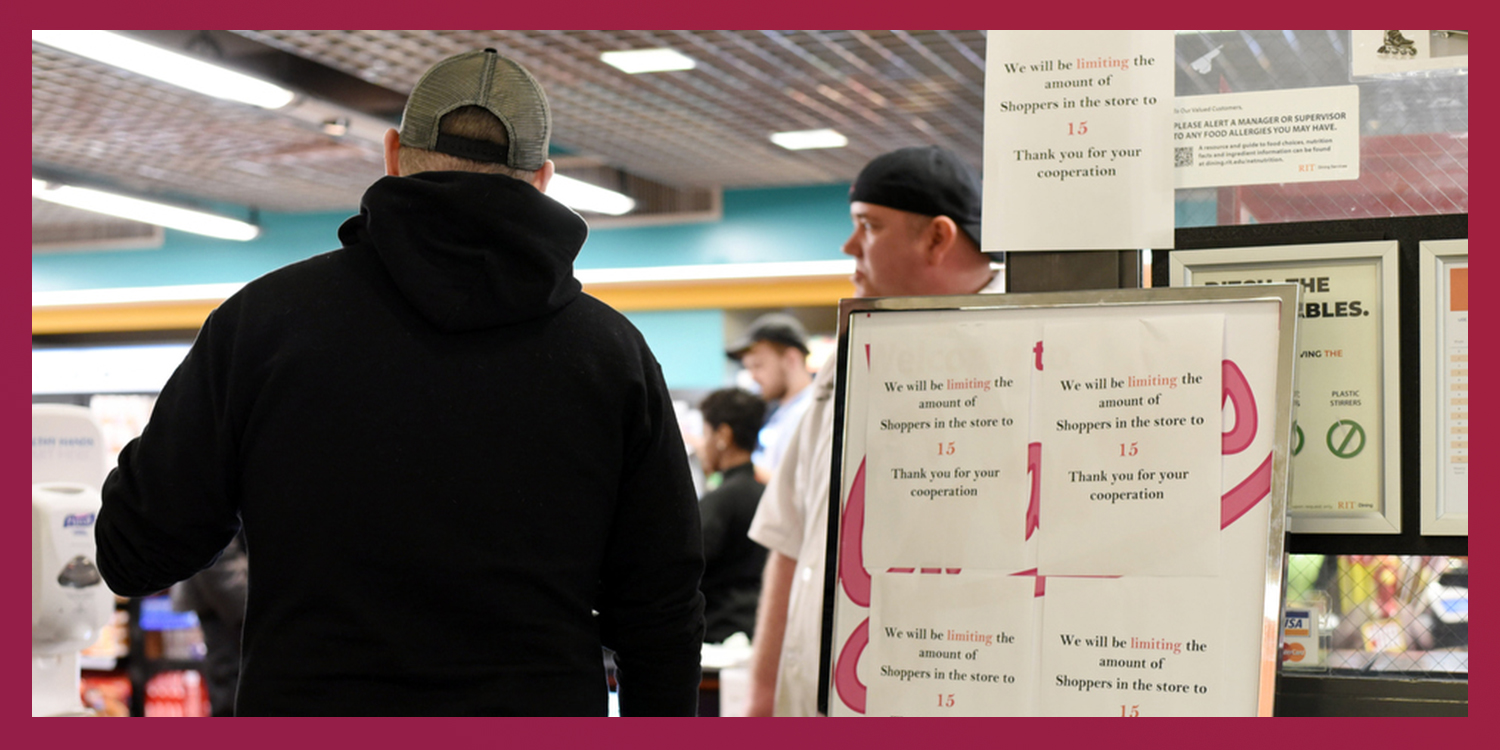

Guidance was also taken from governmental officials. The decision to close campus, for example, was based upon recommendations by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. He enacted provisions limiting the number of people permitted to gather in one place, as well as specific restrictions related to college campuses. Following this, it became clear that continuing normal campus operations was impossible.

Further, RIT has its own internal expertise it was able to leverage. Dr. Wendy Gelbard, associate vice president for Student Wellness, contributed to the discussion around pandemic response. She, among others, provided valuable insight to other administrators on potential risk factors surrounding their decision making.

The Impact

As the pandemic escalates, the response has left a clear effect on the students, faculty and staff of the university.

While most students returned home, some had complications. RIT accommodated these individuals in various ways.

For those who simply could not afford to go home, as transportation costs impeded such unexpected travel, RIT turned to the TigersCare Emergency Fund.

The Emergency Fund was started by an RIT trustee a few years ago, according to Johnson, and has been used in cases in which a student has experienced a one-time unexpected expense that they did not have the financial stability to handle. Examples include relocation after a house fire, copay for a prescription and fixing a pair of glasses. The fund is not used to cover recurring or long-term costs such as tuition.

In this case, the Emergency Fund covered the cost of many students’ plane tickets to return home.

Others, however, had no home to return to. This could be either the absence of a safe place to go, higher risk of infection upon return, an unwillingness to endanger immunocompromised family members or other extenuating circumstances. In these cases, students have been able to remain in their university housing, with the stipulation that they should be prepared to move to an alternate location on campus in the case of potential directives they may receive.

Still more students were placed in self-quarantine. These students, a mixture of quarantine volunteers and those returning from travel through potentially hazardous areas, are remaining in their assigned housing locations, unless it is necessary to move for reasons such as a more private bathroom.

"It’s just not really safe to have people in close proximity to one another right now."

Quarantined students have not been tested for the virus — an important distinction. Rather, those in self-quarantine are either at higher risk of infection or otherwise have self-identified. Many are study abroad students recalled from their travels early. While some returned home, those who returned to campus were often placed into a self-quarantine to ensure they were infection free.

While under self-quarantine, students refrain from contact with others. They are to remain in their rooms and monitor their health over a 14-day period. Their temperature is taken twice per day and any fever is reported to the Student Health Center.

Those students in quarantine are offered a menu of items the night before, and provided their requests. The food is prepared and delivered to their door. Additionally, as Johnson noted, many students order food delivery from off campus.

Yet, Johnson reported that students are still contacting the Center for Leadership and Civic Engagement to find ways to give back to the RIT community despite the pandemic, or to otherwise find ways to give back to their local communities. Throughout this crisis, the Tiger spirit is strong and uncompromising.

Overall, the coronavirus pandemic has left many in a place of uncertainty. Throughout this crisis, RIT has been working around the clock and continues to provide direction, discretion and safety to its student body, employees and community.

“This is a generationally defining moment,” Johnson said. “This is something that we’ll talk about for the rest of our lives.”

While COVID-19 has cast a shadow of fear across the world, RIT, joined by other global institutions, remains steadfast in the common fight against an uncommon virus.