In elementary school, Justin Seo was taught that the Titanic sank because Kim Il-sung, future North Korean dictator, pointed his finger at America and wished ill will. In the world’s harshest dictatorship, ridiculous lies are taught as truth while people die of disease and starvation.

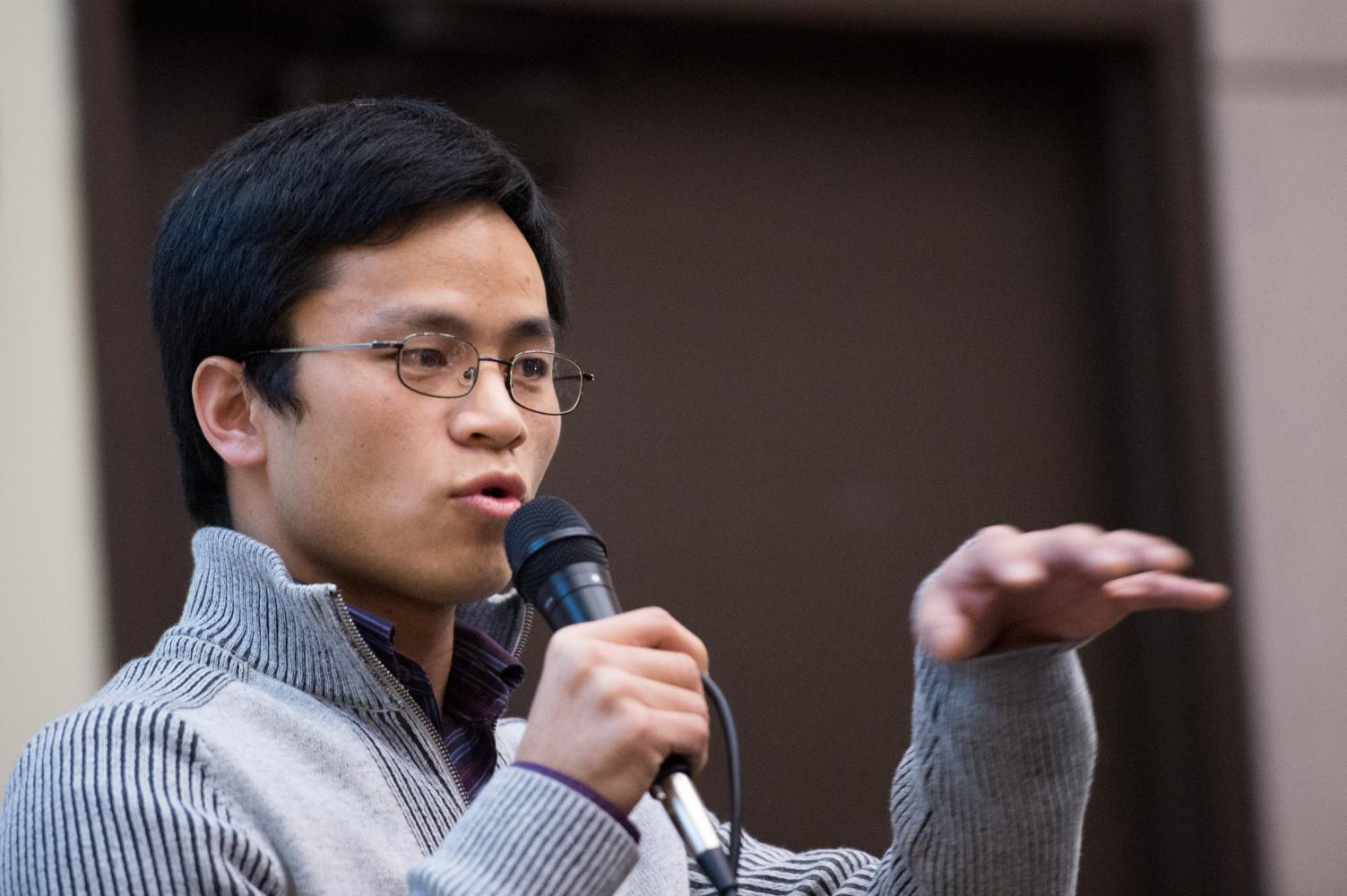

“Death is what I see. What I hear. It’s everything,” Seo said of his life in North Korea.

On Friday, Nov. 17, over 30 people gathered in a small liberal arts lecture hall to hear about life in a country radically different than anything they knew.

The Korean International Student Association brought Seo to RIT to share his story and raise awareness of the plight North Koreans face. Fourth year Industrial Design major Sooa Chung is vice president of the club and helped host the event.

“We wanted to actually tell people about the truth of North Korea. It’s rare that we see a North Korean defector in America … so we thought it would be a unique event,” Chung said.

Though Seo faced many hardships, he talked about his life with humor for an hour and a half, before opening the session for questions. His stories of train hopping, border crossings and jail time kept the audience on their toes.

“It’s very different when someone’s talking about their own experiences, rather than just in general about the entire country,” Yashashree Jadhav, a fourth year Astrophysics graduate student, said.

A Desperate Country

Seo was born in a small North Korean village in 1989. North Korea’s economy had been declining for years, but the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 left North Korea without its main source of economic aid.

Disease and starvation were rampant in the ‘90s. Seo recalled watching his neighbors die of disease in the streets. Death struck his baby sister when he was four years old.

“That was the first time I felt emptiness in my heart,” Seo said. “I loved my sister.”

Seo also caught the disease, but lived. He remembered praying to a higher power, but didn’t have a name for them. North Korea only allows worship of their “Supreme Leader,” currently dictator Kim Jong-Un who inherited the title from his father.

The Kim dynasty began one generation earlier, with Kim Il-sung. U.S. and U.S.S.R. forces cleared the Korean peninsula of Japanese occupation during World War II and divided the country in half, with the Soviet Union given trusteeship of the northern half. They installed Kim Il-sung, a prominent communist with a Chinese education.

As a communist country, North Korea took control of the land and invested in state-owned industries. North Korea’s main industries are military, mining and agriculture. Seo’s mother worked for a government-owned farm, but received only meager rations.

Seo’s father was a carpenter but escaped to China for better economic opportunities. Those opportunities never came, and Seo’s mother had to sell most of their belongings to get by.

“We had nothing at home,” Seo said. “We had dust and chairs."

Seo says the many homeless people he saw pass through his village enlightened him to the depravity of his country. North Korea was not the economic powerhouse it taught its children about.

The Border and Back

In 2005, Seo’s mother gave him money and sent him to a market in the northeast. He was supposed to buy food for his father across the border in China. Instead, he spent all of his money on lodging and food.

He decided to go to China and find his father, but couldn’t afford a train ticket. Seo snuck onto a train, but was caught. His food and bags were confiscated. With nowhere else to go, he clung to the underside of the train for eight hours, with only one short rest.

“If I died, I would be happy because I tried my best,” Seo remembered thinking.

The northeastern border is defined by the Temen river. Seo took the train as far as he could, then crossed over a narrow part of the river into China. Border patrol agents chased after him, but Seo hid in a doghouse in a nearby village.

A dog came by and sat in front of Seo, hiding him from the agents. From then on, he said, he has loved dogs. In the morning, he found a Korean-Chinese woman and she helped him call his relatives that lived nearby. They gave him money, which he hid inside his clothing.

With the money, Seo crossed back into North Korea, wanting to go home. The border agents caught him and brought him in for questioning. The agents asked him if he had any contact with South Koreans or churches, or watched any documentaries.

Seo hadn’t done anything, but they took his clothes and found all of the money. They whipped him until he confessed to crimes he didn’t commit. He spent three months and six days in jail.

There, in the most unlikely of places, Seo found hope. One of the guards smuggled Bibles across the border and snuck candies into Seo’s pockets while pretending to beat him. After the three months, he was transferred to a prison near his home.

Bribery is rampant in North Korea, Seo said. The police force accepted a bribe from Seo’s mother and Seo was allowed to work at the jail and sleep at home.

Seo’s father sent friends to help him escape. They chose to cross a mountain on the border. It was easier to evade border agents but they had to worry about the tigers. The men smoked to keep them away. It took them three days, but they made it to the other side.

Life in China

The abuse of human rights doesn’t end when North Koreans make it to China. In fact, they are exploited as free labor and women face sexual exploitation, according to a report by Anti-Slavery International.

China deports any North Koreans, so they have no legal protection in the country. Seo and his father found work, but soon realized they would not be paid by their Chinese-Korean bosses, so they escaped.

“In China, they would openly discriminate,” Seo said. They say, ‘We can do this to you because you’re illegal.’”

Seo and his father lived and worked in China for two years, until they brought over his mother and brothers in 2007 before one of his brothers was jailed.

“Almost every ordinary citizen goes to jail,” Seo said. “They made it that way so they could easily control [the population]."

In preparation for the Beijing 2008 Summer Olympics, China cracked down on North Korean refugees, according to Seo and the LA Times. The Seo family decided to leave China, but had to make the long journey to countries in the south which would accept them as refugees.

For four days the family rode trains and busses, narrowly escaping encounters with Chinese officials. In one moment, an officer asked Seo for identification, which he could not provide. The officer left, but did not return.

“That was the first time I thanked God ... I felt that supernatural things were happening,” Seo said.

Seo’s family made it to Laos, where they got in contact with the U.S. government and were accepted as refugees. They asked to move somewhere cold, like their hometown. They got sent to Rochester on June 3, 2009 when Seo was 20 years old.

The Transition

Transitioning to an affluent country caused cultural dissonance, which Seo recalls with humor. The audience laughed at his jokes, but the anecdotes reveal how different the two countries are.

In North Korea, the only people who owned cars were government officials, so Seo thought that everyone in America worked for the government.

When showed the apartment they were provided with, Seo was confused. He asked where the kitchen was. In North Korea, his kitchen was a fireplace. Their caseworker showed Seo how to use the stove, but he found it difficult to understand.

“I mean this is too much, I will be starved to death,” Seo recalled thinking.

The other thing that struck him was how big everything was. Animals, plants, food and people were all bigger than what he was used to.

“Is that a cow or a dog?” Seo joked.

Seo now goes to Monroe Community College, studying Information Technology. It was a slow process at first because he had to learn a new language and his North Korean education was lacking.

Seo hopes to return someday to a liberated North Korea and open a technical school. A liberated North Korea is a possibility, but Seo thinks that China needs to be pressured into making it happen.

Seo implored the audience to contact their representatives and ask them to advocate for pressure on the Chinese government. He especially wants to see human trafficking of North Korean women end.

A member of the audience asked if most North Koreans recognized their government’s lies. Seo said he thought most people were disillusioned with the country.

“Everybody wants to escape,” Seo said. “Nobody likes communists. Nobody likes being controlled.”