The past few years have constituted a paradigm shift in the way that we create, aggregate and consume media. Social media and the internet are having an effect on our information dissemination that rivals the invention of the printing press, if not surpasses it. We have unprecedented access to all kinds of information, but the ubiquitousness of the means to both create and consume news and information has facets that range from radiant to dubious to downright dark, and everything in between. Recent events have brought some of these darker and dubious characteristics of the information age to the forefront of conversation, particularly the rise of algorithmic journalism, pervasiveness of fake news and the heyday of the social media echo chamber.

What is Algorithmic Journalism?

Although it is not yet standard practice across the media industry, there has been a recent trend among reputable news organizations such as AP and The New York Times in the use of algorithms, sometimes known as "bots," to write certain stories like financial reports and sports summaries. These algorithms allow news organizations to produce more timely, accurate and frequent news updates; AP's engine was able to produce up to 2,000 articles per second back in 2015, and who knows what it's capable of now.

There is a certain concern among the industry that this will lead to the elimination of the need for human journalists, but RIT's Andrea Hickerson, director of the School of Communication, doesn't see that happening anytime soon.

"What happens is you lose a lot of context when you look at that stuff," she said. "So it would have to be things that didn’t need a lot of interpretation." Hickerson believes that while these algorithms are very adept at producing routine, data-heavy stories, they don't have the capacity for analysis and interpretation that a bona fide human journalist would bring to the table. Algorithms can't react and adapt the same way a journalist could; they can't ask questions, think critically or explain context. However, they may prove to be an invaluable asset to the modern-day journalist by freeing them up to delve deeper into more nuanced stories.

"If you could have the sports scores automated, then you could go work on an investigative story about steroids or something instead," said Hickerson. There was a caveat to this, however — since the algorithms focus on keywords and data points, they are effectively acting as a filter to what both journalists and the public see. Hickerson believes that it's important to have a check in place to make sure that filter isn't altering the actual story or situation.

"Some of the digital tools that we have are really good methods of collection, like information gathering, but that doesn’t mean they’re publishable as-is," she said.

Algorithms may prove to be an invaluable asset to the modern-day journalist by freeing them up to delve deeper into more nuanced stories.

While not inherently connected, algorithmic or computational journalism and the pervasiveness of fake news have both recently been on the rise, and there is some speculation to the correlation between the two. The most obvious connection is the recent controversy surrounding the Facebook news algorithm: While Facebook does not actually compose any of the stories that appear on its trending news feed, either algorithmically or conventionally, it does use an algorithm to choose what appears as "trending" topics. The removal of human curators to an entirely algorithm-run process was intended to reduce the possibility of liberal bias — which Facebook had been accused of in the past — but almost immediately backfired when an entirely false story from an unreliable source made its way to the top of the list.

While this may seem like just a hiccup in the implementation of a new technology, the backlash on the internet has been ongoing. Facebook has been denying responsibility for fact-checking and taking a stance on what to classify as "news." They see themselves as more of an aggregation platform that shows users what they would like to see, without being the one that has to make a judgment call. However, since 62 percent of adults get at least some of their news from social media, they may have more responsibility than they would like to admit — but then again, so might we, as users of those various platforms.

"I think that part of this dialogue about the media has to shift on us, because we’re clicking it, we’re sharing it, and then we’re not calling people out on it or asking questions," said Hickerson. Because we have been so afraid of appearing impolite by talking about politics on social media, we are allowing the spread of news that we know is at worst blatantly false, and at best misleading.

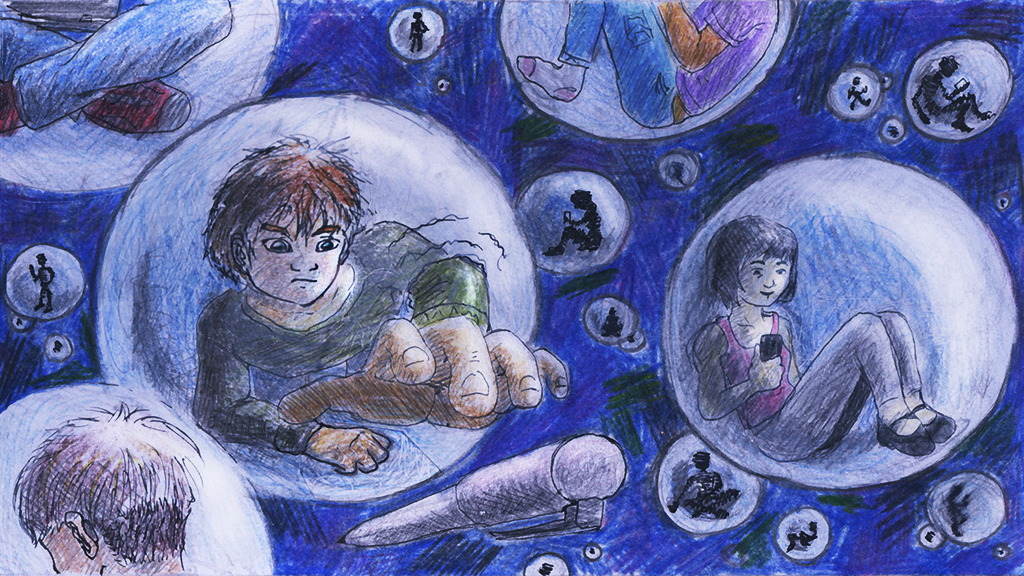

Although we may not understand the intricacies of Facebook's News Feed algorithm, we know that it recognizes which posts you interact with — whether it's by liking, commenting, sharing or just clicking — and shows you more of the same types of posts. This has led to a phenomenon known as the "social media echo chamber," which is yet another byproduct of the information age that we have constructed for ourselves. If we only interact with posts we agree with, we will only see more and more

How to Break Out of the Bubble

First: Stop blaming "the media." There was no golden age, no time in history when the media was a paragon of bipartisan, agenda-less information output. Even the idea that the media is a single entity is rooted in misconception, according to Hickerson. In fact, even the idea that the media should be objective is relatively recent.

"There was still corruption in the media, people were still doing awful things," she said. "And if we go back to the beginning of colonial times, the people that ran the media were the people that could afford the printing press, because it was really expensive." It wasn't until the '20s, she continued, that we started to expect the media to be impartial.

The second order of business is to actually look at the source of the material you're posting, specifically the date, the originating website and where that website gets its money. "I think now we’re starting to see people talking about this and saying, 'This is how you should look at websites,'" said Hickerson. The first step to remedying the issues of the social media echo chamber and the rise of fake news is to be more cognizant of what we are reposting and whether or not it is from a reputable news source. It's easy to only pay attention to those things that confirm what you want to hear, but continuing to block out anything that contradicts our own views is just like going to bed after a night out without drinking a glass of water: you're just asking for a hangover.