Investigating Diversity and Inclusion at RIT

by Alyssa Jackson | published May. 16th, 2016

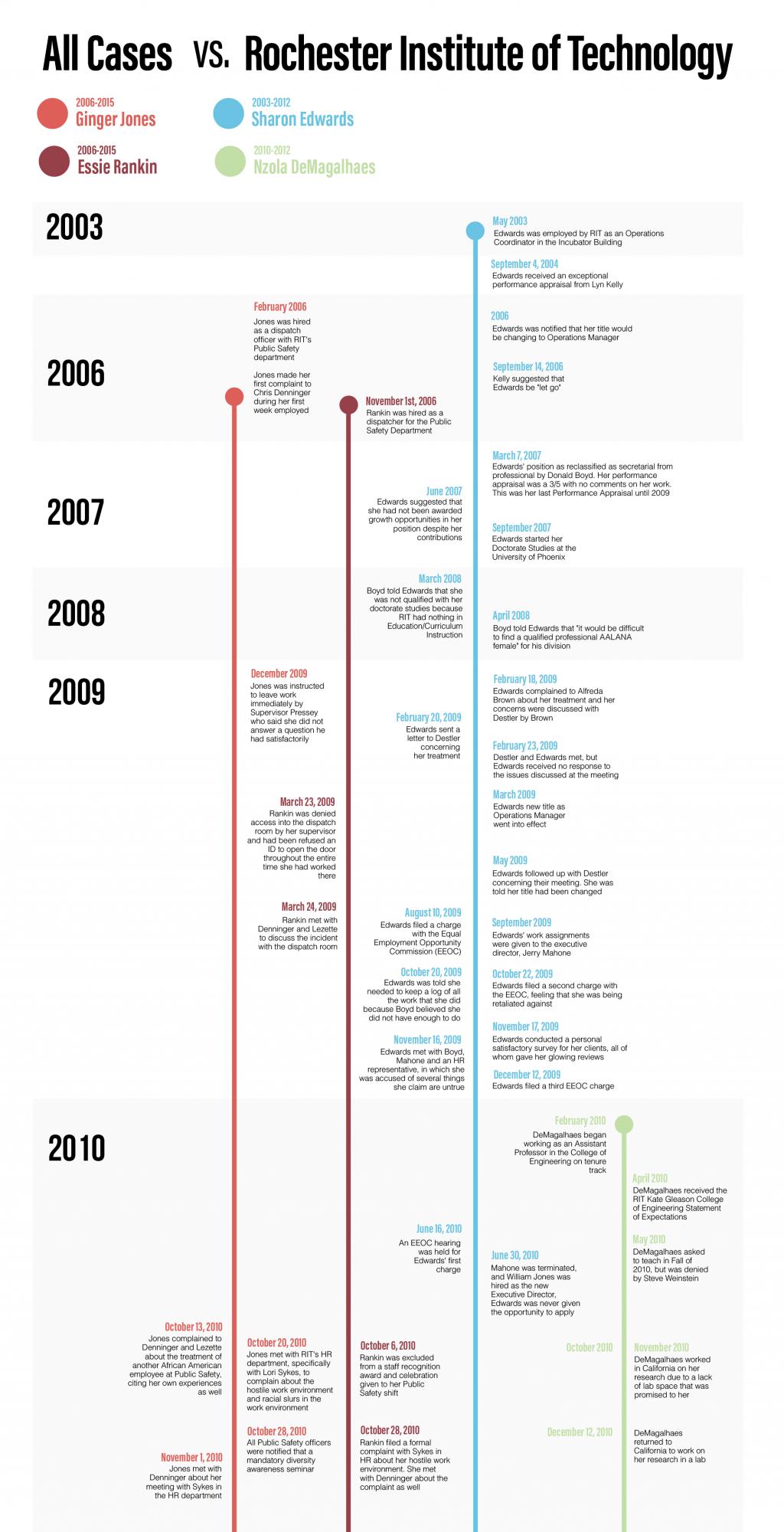

Diversity may be an ideal that RIT strives for, with its new strategic plan promoting “greatness through difference,” but three lawsuits filed against RIT show a different climate. Four African-American women — all former employees — are alleging discrimination in the workplace.

It’s not unusual for RIT to be involved in lawsuits, particularly lawsuits that accuse RIT of being discriminatory, according to Bobby Colon, RIT’s General Counsel for the Office of Legal Affairs. As New York State is an employ at-will state, employers do not need to give a reason for terminating an employee. This may cause some employees to attribute their termination to their gender or race. With RIT known as an economically sound employer, lawsuits are a norm for the Institute.

RIT’s President Destler said that he has seen lawsuits regarding discrimination of gender and ethnicity plenty of times throughout his tenure at the campus, although they’ve never had one come out unfavorably for RIT. He and Colon were unable to give a specific number.

“We’ve never had a real finding, but it does raise questions about our processes,” Destler said. “These issues are interrelated, and we need to create an area of comfort.”

Typically the university will try to handle a problem before it reaches the point of legal action. RIT’s human resources (HR) department works with employees to investigate all claims of mistreatment on the basis of gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation.

“RIT has a specific policy,” said Judy Bender, Assistant Vice President for HR. “If any concerns come to HR, it’s investigated. We talk to the person, gather data, talk to witnesses if there are any, and then make a determination.”

In addition, faculty and staff go through diversity training on campus. Currently, the HR department is working to develop training for faculty and staff that will educate them on unconscious bias.

“We have more programs in place now than we did in the past,” said Bender.

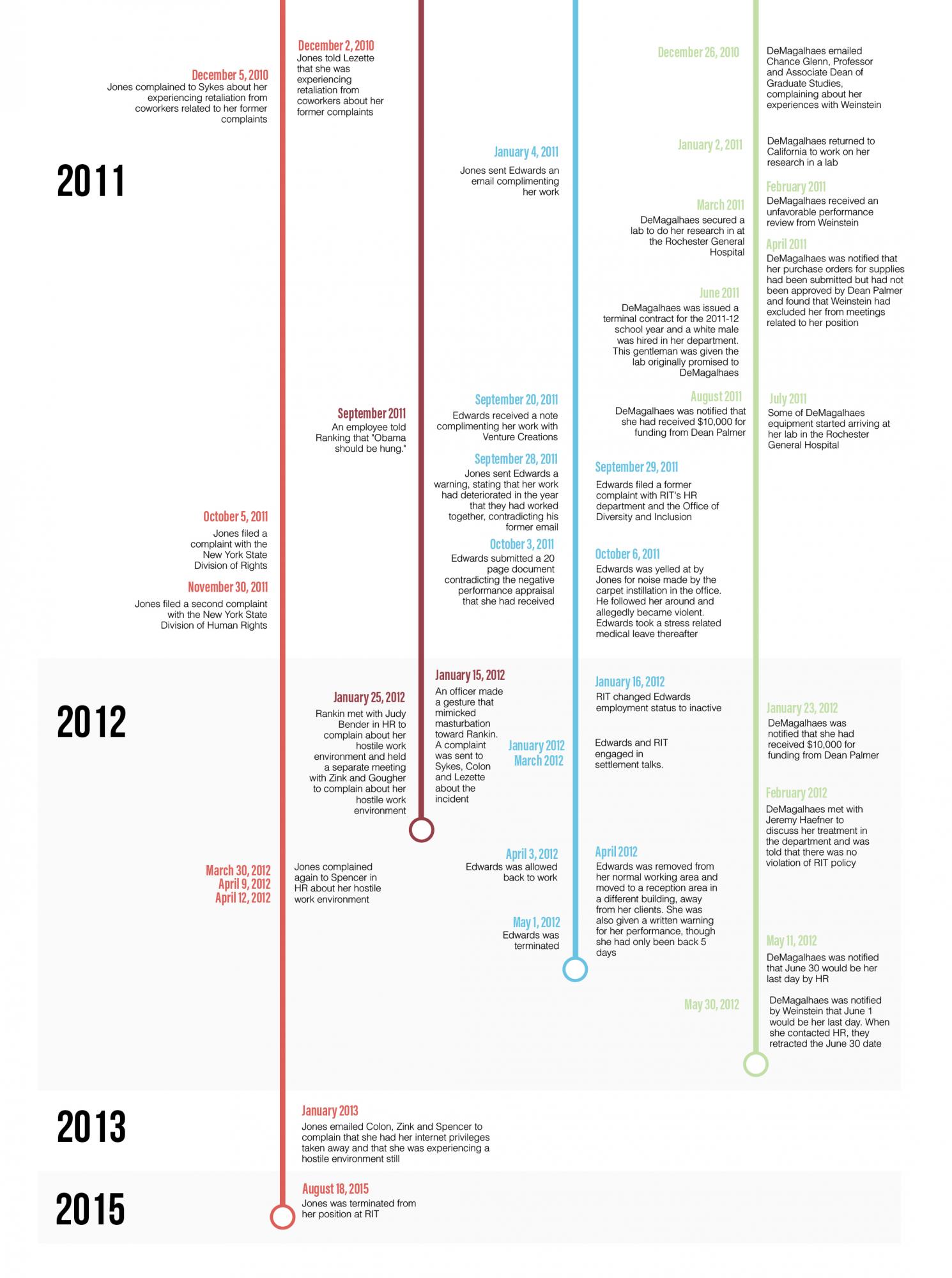

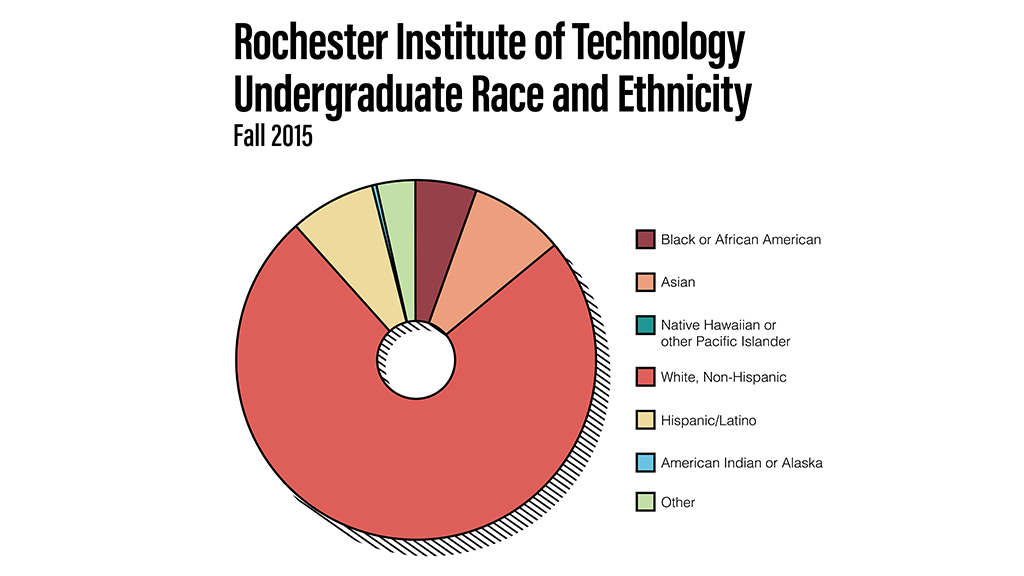

Currently, RIT has a 15.3 percent AALANA African-American, Latin American and Native American (AALANA) student population on campus and a 25.2 percent Asian, Latin, African and Native American (ALANA) student population as of fall of 2015. These numbers include undergraduate and graduate students and exclude students who chose not to provide this information so as not to skew the numbers.

As a point of comparison with other universities, consider these numbers: according to statistics from 2014 stated in the 2015 Annual Diversity Report by University of Rochester’s President Joel Seligman, 3.9 percent of the faculty identified as an underrepresented minority, while underrepresented minority enrollment at the university was at 9.6 percent. In comparison, according to numbers provided by Forbes, 10.51 percent of the student population at Hobart and William Smith colleges are Native American, African-American or Latin American. According to these numbers, RIT has a more diverse student population than other colleges in the area.

Full-time faculty and staff trail behind shortly, with 12.5 percent of the population identifying as Native American/Alaskan Native, Hispanic/Latin American and Black/African-American, according to numbers provided by the Office of Diversity and Inclusion on campus. We do not know how many of these individuals are tenured or tenure track faculty, or how many minority faculty and staff have been promoted in their time here.

Numbers for diversity among faculty and staff are not typically shared publicly by universities. Diversity among student populations is required to be publicly shared by colleges accepting federal funding.

Each of the lawsuits is explored below in detail. All three lawsuits are brought by African-American women who were former employees of RIT. All of the cases are represented by the Reddy Law Firm in Buffalo.

Ginger Jones and Essie Rankin vs. RIT and Chris Denninger

Ginger Jones was employed with RIT’s Public Safety Department in February of 2006 as a dispatch officer. She said that she was met almost immediately with inappropriate behavior at the hands of her superiors. On her first day she was asked by Supervisor Jim Pressey if anyone had shown her where to take out the trash.

“How does a dispatcher equate with taking out the trash?” Jones asked in an interview. “After a few days I decided to go forward and voice my feelings about that complaint to Chris Denninger (director of Public Safety). I had a meeting with Denninger and he said that he was raised in a household where women were not expected to take out the trash so he said he understood how I could be offended by that, but he didn’t seem to understand the racial implications.”

This interaction was the start of a chain of events that occurred until Jones was fired in August of 2015. Jones complained of inappropriate videos being played in the dispatch room, sometimes of black men being beaten by cops using racial slurs.

Jones stated that she often heard officers in the department referring to rape and sexual assault survivors as “bitches, sluts and whores.” Officers would jump to conclusions in rape cases, claiming that the student deserved it or was lying. Other times, Jones said that she witnessed cameras in the dispatch room being used to view attractive women, people changing in cars or people making out on campus.

Racism in the department didn’t stop at videos, according to Jones. Once she heard an Asian student referred to as a “slanty-eyed gook.” At an event held by an African-American fraternity on campus, she overheard two officers saying, “They don’t need to be here, they need to just leave, why in the hell have them back here when they don’t know how to act? Get your pepper spray and Tasers ready.”

In addition to these complaints, Jones also said that she was not given the opportunity to work overtime hours, even though every other officer was. She said that she was not given access to the dispatch room where she worked for several years, even though all other employees had access. There were times when her supervisors would shut the door and laugh at her attempts to enter.

When she complained about these things to her supervisors, Denninger and the HR department, she was largely met with silence, she said. After one complaint with HR, all of Public Safety was mandated to attend a diversity training seminar, but Jones said that it did nothing to stop the offensive behavior she was witnessing.

Jones and Essie Rankin, another female African-American Public Safety officer, met after a staff meeting that got particularly heated. Rankin ran to the bathroom in tears and Jones met her there to check on her. It was there that the two realized that even though they worked different shifts, they were sharing very similar experiences.

Rankin was hired in 2006 to also work as a dispatcher for Public Safety. She witnessed the offensive videos and was also denied overtime. Pressey, a supervisor with Public Safety at the time, frequently locked her out of the dispatch room, which she was not given access to for a number of years as well. She experienced racist and sexist comments. For example, Rankin said that another officer told her that “Obama should be hung.”

When she was in the dispatch room, she also noticed the misuse of cameras to look at women on campus or to view porn. When she reported an instance of an individual watching porn in the dispatch room to Denninger, she was met with indifference, she said.

“He said ‘RIT is a very liberal institution. Was it kiddie porn?’” Rankin said. “How dare they think that it’s okay to be sitting in a room where you’re supposed to be doing your job and they are watching porn. ‘If RIT had a problem, they would block it on their computer,’ he said.”

“How dare they think that it’s okay to be sitting in a room where you’re supposed to be doing your job and they are watching porn."

Rankin, like Jones, complained to Denninger and the HR department several times throughout her time with the Public Safety office to no avail. HR was unable to comment on the case because it is still moving through the legal system.

In August of 2015, Rankin and Jones were terminated from their positions. According to the court document, “upon information and belief, no other employee was discharged.” At this point in time, Rankin and Jones had already filed the lawsuit against RIT and Denninger for the creation of an unabated hostile environment and discrimination.

Denninger did not respond to multiple requests to comment for this article. Destler explained that he had heard of the situation and understood there was an investigation of the claims, but he was unsure of what the results of that investigation were.

According to Prathima Reddy, Jones and Rankin’s attorney with The Reddy Law Group out of Buffalo, RIT has stated that the women were terminated due to a downsizing of the department. However, in a Reporter article from February of 2016, Denninger stated that the Public Safety department would be growing soon to accommodate a new firearm policy for the university. Discussions and plans for these changes started well over a year ago, according to Denninger.

“I think it goes a long way to say that the two women who were employed there were treated wrongfully,” said Reddy. “So, what we’re really focusing on is the hostile work environment, and it’s very brazen of the officers to not only allow the behavior but take part in it. Really the issue is that no one at RIT took the steps to remedy the situation, particularly because the director’s involved.”

"Really the issue is that no one at RIT took the steps to remedy the situation, particularly because the director’s involved.”

Currently, the case is in litigation awaiting deposition. The two women are ready to move forward with their lives and hope that the case will bring change to the department for future women and women of color. Reddy said that the women have been unable to find comparable jobs since their termination.

“I hope that no other person will have to experience what I experienced,” Rankin said with tears. “Every time I think about others in the business who didn’t have the capacity to do what we had to do… I just hope that never happens again.”

Nzola DeMagalhaes vs. RIT

Nzola DeMagalhaes began working for RIT in February of 2010 as an Assistant Professor in the College of Engineering on tenure track. She was recruited while living in California by RIT’s diversity hiring committee. When she came to tour the campus, it seemed like the position was straight from a dream. She would be working with the new Biomedical Engineering program.

During her tour before accepting the position, she was shown a laboratory that would be hers to use for research. Her contract included an equipment budget up to $100,000. She was given a list of expectations to obtain tenure, which included teaching, competency in research and completion of professional service activities.

In her first weeks here, DeMagalhaes said she was made uncomfortable by her direct supervisor, Steve Weinstein, chair of the department. She said that in meetings he would frequently sit next to her rather than across the table from her and that he would make inappropriate contact with her, such as rubbing her shoulders. When she would request that others be present in their meetings or that they keep his office door open, Weinstein would get upset, according to court documents.

Moreover, DeMagalhaes found that she did not have the lab that was originally promised from her. She would never gain access to the lab that she was shown on her visit, but a male employee hired after her would. The court documents do not state whether this lab was part of her contract or if she was just promised it during her tour. Instead, after approximately a year of waiting, DeMagalhaes had to do her work from a lab in the Rochester General Hospital.

Upon securing this lab, DeMagalhaes still could not begin to work on her research as it proved increasingly difficult to obtain the supplies that she needed. She said purchase-order forms would get stuck in the approval process, or she would find that she was given far less money than originally stated in her contract.

In May of 2010 she requested to teach the following fall, but was told by Weinstein that she could not teach until the 2011-2012 academic year, and even then it would only be co-teaching. Even in the 2011-2012 academic year, Weinstein was told that she could not teach due to the conversion from quarters to semesters.

By the time she began to get the necessary supplies, DeMagalhaes had only four months to complete her research. This was an insufficient amount of time, she said. Despite the fact that she said she had complained to Weinstein, Chance Glenn, associate dean of Graduate Studies, Dean Harvey Palmer and Jeremy Haefner, provost and associate vice president of Academic Affairs, she believes she was not given the tools to allow her to adequately do her job here at RIT.

DeMagalhaes was terminated on June 1, 2012, after being told that her last day was June 30 by the HR department at RIT. She later filed a lawsuit for employment discrimination with The Reddy Law Group. Reddy also represents DeMagalhaes as an African-American female formerly employed with RIT.

“I have interviewed several African-American professors that were denied tenure at RIT,” Reddy said. “There seems to be a consensus among minority professors that RIT will hire minority professors to have bragging rights, but after a time they are denied tenure. The tenure minority professors are very limited which is unfortunate because they bring on a strong candidate, but when they are denied research or tools that would allow them to get to the tenure stage, they are at a disadvantage.”

HR was unable to discuss this case as it is currently pending in the court system.

DeMagalhaes was unable to comment on her case at the time of print due to its status in the court system. Weinstein was also unable to comment, but said “It’s unfortunate when communication breaks down.”

However, Weinstein said that he enjoys a very diverse team in his department and that he is proud of their work.

“Our department has more women than men in professor roles,” Weinstein said. “It’s important to have a diverse faculty. You need to have diverse people for students to connect with, and that’s the biggest reason to have a diverse group.”

Sharon Edwards vs. RIT and Dr. Donald Boyd

Sharon Edwards began working at RIT in May of 2003. She originally started as the operations coordinator in the Incubator Building, now known as Venture Creations, on campus. She worked closely with Donald Boyd, the former vice president for research.

Edwards said that she had always received glowing reviews from her supervisors until 2006, when supervisor Lyn Kelly suggested that Edwards should be fired. Around this time, Edwards expressed dissatisfaction that she had not grown in her years at Venture Creations.

In 2007, Edwards received a performance appraisal that was much lower than normal. According to her, this was the last performance appraisal she received for several years, which is against RIT’s E27.0 policy.

Edwards stated in the court documents that until her termination in 2012, she had been passed over for several positions that she felt she qualified for. In one instance, Edwards said that Boyd had said, "It would be difficult to find a qualified professional AALANA female" for his division.

Edwards complained to Alfreda Brown, former interim chief diversity officer, Destler, the HR department and filed several motions with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The complaints allowed her change in title to finally be enforced. She had been promised a change in title from operations coordinator to operations manager. However, she still felt that she did not get the growth opportunities she deserved.

Edwards was also unable to comment on her case at the time due to legal proceedings. Boyd, Edwards’ supervisor, remembered Edwards and her other supervisor, Jerry Mahone, fighting frequently. “She just had to have everything go her way,” he said.

When asked further about the accusations from Edwards, Boyd declined to comment.

“We are uncovering a pattern and practice of disadvantaging minorities at RIT despite leadership at RIT claiming a commitment to diversity and inclusion,” Reddy said. “These lawsuits indicate a widespread problem amongst various departments of the university.”

“We are uncovering a pattern and practice of disadvantaging minorities at RIT despite leadership at RIT claiming a commitment to diversity and inclusion,” Reddy said. “These lawsuits indicate a widespread problem amongst various departments of the university.”

HR declined to comment on the case as it is still moving through the court system.

Each of these cases is at different stages in the legal process. Reddy, the attorney representing these women, explained that we may not expect judgements on the cases for months or even years.

“My greater hope is that RIT as an institution changes as a whole,” Reddy said. “You should have a diverse and inclusive student population but more importantly a diverse professional staff.”