“Sometimes I feel scared. I like to walk by myself, but I just worry that someday one of those guys I’m just walking past and ignoring is going to start chasing me or something,” said Laura Lee Jones, a Fine Art Studio major who just graduated this winter.

Jones is not the only woman to experience this dilemma. A 2014 survey commissioned by Stop Street Harassment found that 65 percent of women had experienced street harassment and 20 percent of those reported that they had been followed by their harasser, although other studies have found higher numbers. This harassment can be a once in a lifetime instance, or it could happen more frequently.

“I’ve been catcalled basically every time I leave my house, because I live in the middle of the city and I walk a lot. It’s infuriating,” Jones said. “It’s infuriating.”

Harassment occurs beyond the city, too, whether in the Wegman‘s parking lot or on campus.

Donna Rubin, assistant vice president for Student Wellness and the previous director of the Center for Women and Gender, recalled one incident during her time as director in which boys within a residence hall were holding up cards with numerical ratings of the appearance of the women walking by. Although she didn’t hear many more reports, Rubin said she doesn’t doubt that it happens frequently.

“I’m sure there are many more that didn’t report, because there are some people who aren’t offended by it, and some who are offended that don’t report.”

The differing interpretations of catcalling between those doing the calling and their subjects, and among the subjects themselves, is one reason that some still view it as a non-issue or even as something complimentary.

Darci Lane-Williams, the current director of the Center for Women and Gender, explained “You should be able to take the same compliment and give it to anyone and have it have the same impact,.” Darci Lane-Williams, the current director of the Center for Women and Gender, explained, givingShe gave the example of telling someone she liked their boots. “I can say that to a guy, I can say that to a girl, I can say that to a child, I can say that to an elderly person, I can say that to anyone.”

Catcalling is very different. A sexual tone is often implied, and it is often an evaluation of the subject’s body. The comment, whistle or other verbal expression is usually made specifically because the subject was female or gay, or because of their gender expression. Those who experience street harassment are disproportionately women and LGBT individuals and, no matter who is being harassed, the harassers are overwhelmingly male.

When it happens to a straight man, however, it also can have a very different impact, explained Ian Scott, a fourth year Civil Engineering and Technology major who experienced street harassment once in a Wegman‘s parking lot when a man shouted “Nice ass!” at him from a car.

After the incident, Scott said “I felt fine,” Scott said.. “It just made it apparent that other dudes check me out … That was just an isolated incident for me.”

For most that experience street harassment, the survey commissioned by Stop Street Harassment found that the impacts were wider and affected how the individuals behaved in the location of the harassment and beyond in the future.

According to Rubin, catcalling itself is an uninvited public evaluation of someone based singularly on their appearance, and this is part of the reason she and others find it disrespectful and unnerving even if the comment is intended to be positive.

Naomi Kimmy, a fifth year Game Design and Development major, said she has heard catcalls both on and off campus ranging from someone telling her they wanted to “rape her in the ass” to telling her that they liked some stockings she was wearing. She describes the latter as threatening, not because of what was said, but because it was said to her when there was no one else present but her and three guys and because the one making the statement deliberately encroached on her personal space. Lane-Williams explained that when it comes to street harassment

“Sometimes it’s not even what you say, sometimes it’s how it’s said,” Lane-Williams explained. “T the eye contact or the lack of eye contact, because they are looking somewhere else on your body.”

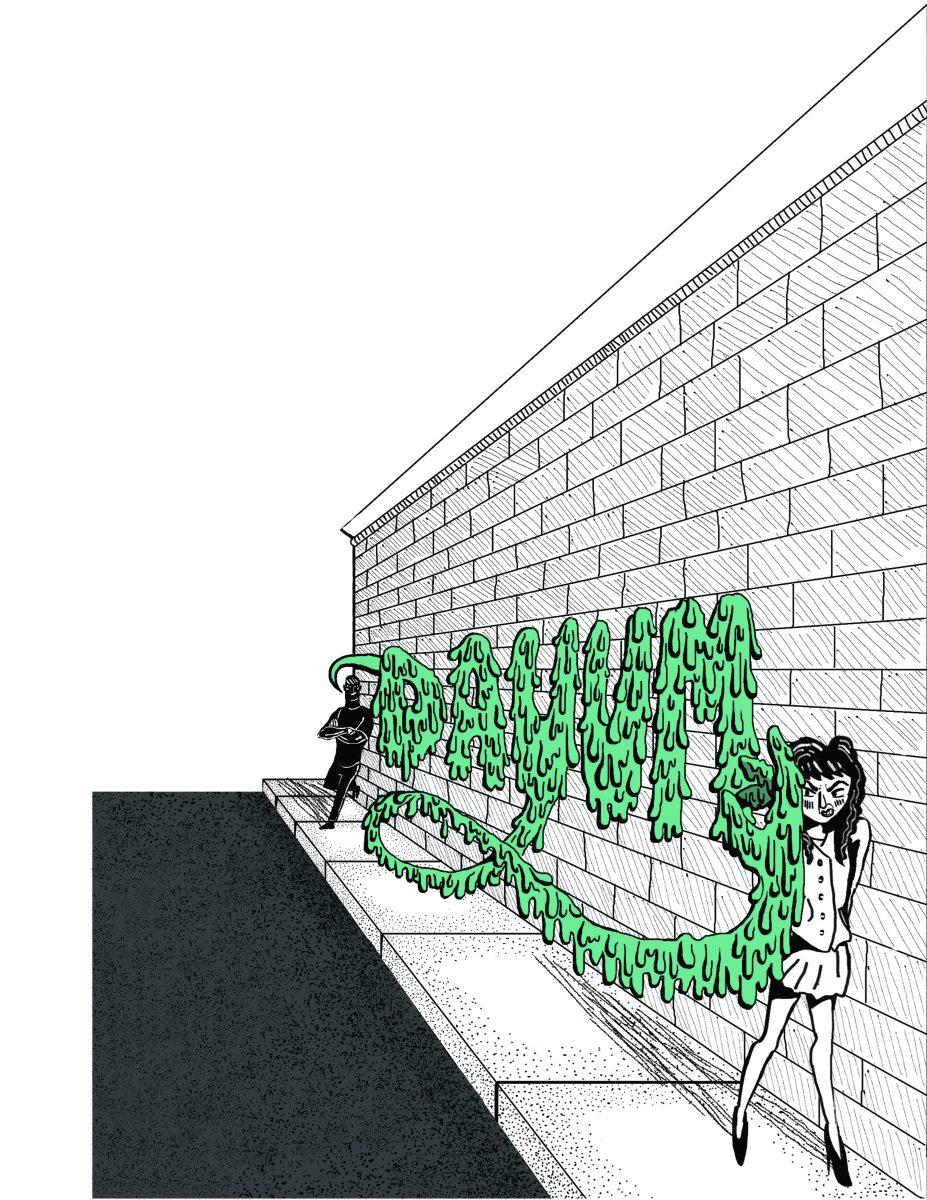

These are creepy situations to say the least, but many who engage in street harassment and catcalling choose to stick with the classics.

“It’s really often that people are just like ‘Hey cutie!’ ‘Hey sweetie!’ ‘Hey come here, hey come here!’ There’s a lot of ‘Hey come here,’ ‘hey what’s your name’ … If I don’t say anything there’s a ‘Fuck you’ or something like that,” recalls Jones. “‘Can I get a ride?’ That’s a common one, especially when I’m riding my bike. Or ‘I wish I was that bicycle seat.’ Really gross stuff.”

These gross comments, and the more neutral ones alike, have an impact on their subjects — both on the way they feel within themselves and within the public spaces they occupy.

“It makes me feel physically sick when I get catcalled. It’s definitely violating, and I have a physical response to that. It makes me angry, and I don’t like being angry, but I’m trying to see it as an opportunity to find Zen,” said Jones.

Zen, however, can be difficult to achieve in the situation, especially when the harassment affects the way the subject views the space they are in. “It leaves you sometimes feeling the need to check behind you to make sure you aren’t followed on campus,” said Kimmy.

Lane-Williams said she believes that no one should have to experience this feeling, especially on campus.

“Every college and university has a responsibility to create a safe environment for all students. … Yyou should be able to walk to class without fear or concern for your safety. You should be able to sit in your class and fully concentrate and learn, because you’re here to learn and if there is something in your environment keeping that from happening, it’s our responsibility to address that.”

An issue arises in how exactly to address catcalling and street harassment. The university can play some role if and when cases are reported, but its jurisdiction doesn’t extend far beyond the green lawns surrounding campus. When determining how to react as an individual, choosing the appropriate course of action can be even more difficult.

“I’ve tried all different types of responses! I’ve tried ignoring people, which seems to be the best thing, even though it feels like you’re not accomplishing anything by ignoring them,” said Jones. “But I’ve yelled back or just started flailing my arms around like a crazy person, and I don’t know, that stuff just leads to more verbal abuse. I just try to ignore it now. I’ve tried having conversations.” But in her experience, attempted conversations about the harassment that just occurred were usually ignored by the other party.

This has left Jones feeling most comfortable ignoring the people who harass her. Kimmy, and many other subjects of catcalling, also follow this strategy. “Unfortunately, in the situations you don’t always know if you are going to be physically or verbally attacked.” Kimmy usually tries to be nice and go on her way in order to avoid such conflict.

Lane-Williams agreed that in situations where there are higher probabilities of confrontation leading to a more dangerous situation, such as when you don’t know the area or the person or that person is far from sober, ignoring the affronts and leaving the area may be the best approach. However, she also believes that the communication that can be spurred by these interactions is very important, especially when on campus.

“[RIT] is the environment where it should be safe – should be, ideally – to say, ‘I don’t like that,’ because there’s a very good chance you are going to see this person again. You may be sharing space in the same building for classes,” said Lane-Williams. Responding can help educate the person catcalling on campus – a person who, after all, is supposed to be here to learn – and can help establish boundaries for what acceptable behavior should be within the campus community.

“We have to create a culture in which people understand this is a problem, that it’s not complimentary, that it is an issue, but any time you are dealing with people and boundary-setting, you are always going to have difficulty – always,” Lane-Williams said.

Rubin said she imagines that it is often easier for a person to step in when they are not the subject of the harassment, too, and the help would be much appreciated.

“Could you imagine if all the people and all the bystanders and everyone within earshot [of the harassment] said, ‘Hey, that’s not cool’?” asked Lane-Williams. She said she guesses that the person catcalling might be less interested in that activity in the future.

Although her perspective differs slightly from Lane-Williams, Jones also advised that subjects of street harassment continue to express empathy. “I would say just ignore it and try to have empathy. That’s what I try so hard to do!” said Jones. “Have empathy for that person, because they are obviously lacking something in their experience, too. I don’t know. It’s really hard to do.”

Asked ifIf she could asksay one thing to the individuals who catcall, without risk, Jones said; “I would just say ‘I see you, I recognize that you are a human being. Can you do me that solid too?’”