It’s 1956. David A. Anderson walks into the RIT Housing office, looking for a place to settle as he begins his education. Unlike the warm welcome he might receive today, Anderson is met with a turned back and a short reply: “Got no room.”

Roughly a year ago, the Democrat and Chronicle shared Anderson’s story, as well as the stories of many others, as the newspaper revisited the culture of the 1950s and ’60s and what lead to the Rochester Race Riots of 1964. Pick up any high school history book and you will find just a few mentions of Rochester; the triumphs of Frederick Douglas and Susan B. Anthony will most certainly be mentioned, as well as the glory days of the Flower (Flour) City boom and the Kodak era. But one of Rochester’s most notable, and most infamous, claims to fame remains the Race Riots of 1964.

When we look back at the riots of 1964, we have less reason to celebrate our progress and more reason to lament our lack thereof.

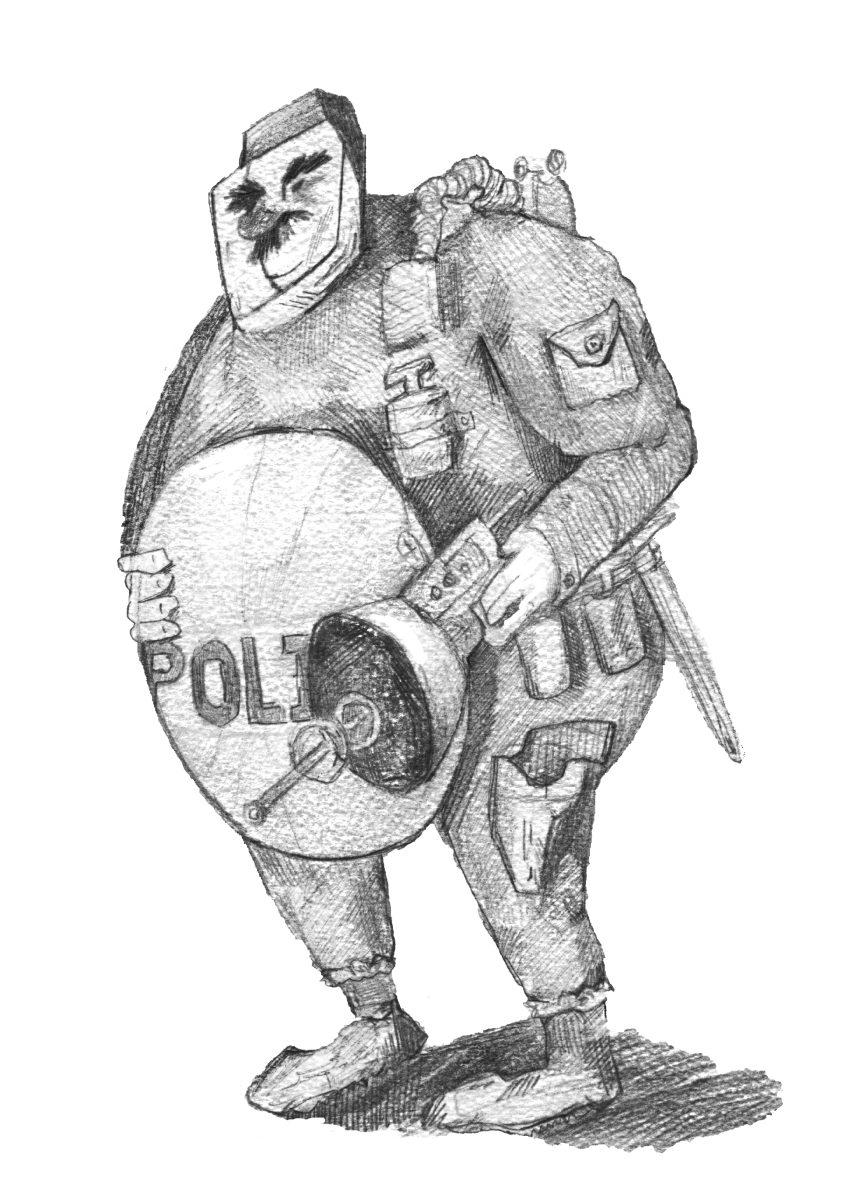

What should have been a routine arrest escalates into one of the most famous riots in United States history as the crowd reacts to the dogs, which had been symbols of oppression and police aggression ever since the Birmingham riots a year prior. Word spreads of a pregnant woman being slapped by an officer and a young child being attacked by one of the dogs. Before long, rioters begin to congregate on Joseph Avenue, right next to Nassau Street. All in all, some 400 people join the protest that Friday evening, and all available police officers are forced to respond.

Over the next three days the riots caused the deaths of five individuals — four of which result from a helicopter which crashed while surveying riot damage — and the destruction of around 200 local stores. The riots only end after the National Guard is called in to a Northeastern city for the first time in history, and the “Rochester Race Riot” makes headlines across the nation, sneaking its way into the history books.

2014: Fast-forward 50 years after the Race Riots, and the populations of both the city and the suburbs have diversified significantly, with the percentage of

The current

One would hope, and expect, that racial discrimination has been on the decline since the ’60s, but there was much more behind the riots of 1964 than just racial tension. A series of PBS articles created in company with a documentary about the three-day riot suggest that it was the release of a long-developing tension caused by crowded housing and a severe lack of job opportunities. These sources of tension sometimes fly under the radar of what has been titled a “race” riot.

“People were stunned as to how could this happen in Rochester, you know, an affluent eastern city that had a reputation of being very benevolent and generous,” explained Frank Lamb, the mayor of Rochester in 1964, to PBS.

Jennifer Leonard, president and CEO of the Community Foundation, points out in a quote from a Democrat and Chronicle article that perception and reality remain to this day two very different things when it comes to Rochester.

“We live such segregated lives — rich and poor, educated and not educated, people of color and whites — Rochester has made it possible for a majority of the population to remain blissfully unaware of the challenges of the other part of the population.”

Rochester has more people living below the poverty line than all but four other U.S. cities.

A prime example is the neighborhoods in which the majority of the rioting occurred in 1964 and where

Perhaps the city of Rochester isn’t so different now than it was at the time of the riots over 50 years ago. Perhaps the city of Rochester is still a powder keg awaiting the next spark that will send its impoverished citizens into chaotic action. The riots in Baltimore and Ferguson have shown that citizens still have the same concerns they did 50 years ago at the time of revolt in Rochester.

Equality and opportunity, or the lack thereof, are constantly on the forefronts of our minds. Where there is inequality and impoverishment, there will always be the capacity for riots and the chance another city will wander its way into the headlines in the worst way. However, if we keep working together as a nation and a world to rid ourselves of these issues and the many others that plague societies around the globe, maybe one day we will live in a world where events like the Rochester Race Riots are only a lesson that we teach our children so that they might not repeat our mistak