Deaf cultural clubs offer spaces for RIT and NTID students to socialize and celebrate their culture amongst signing peers. Recent plans to replace club spaces — including the transformation of the Student Development Center’s (SDC) club rooms into multi-club shared spaces and the conversion of the Club Suite 2.0 office into NTID faculty offices — pose particular challenges for clubs tailored to Deaf students of color.

Intersectionality and Deaf Clubs

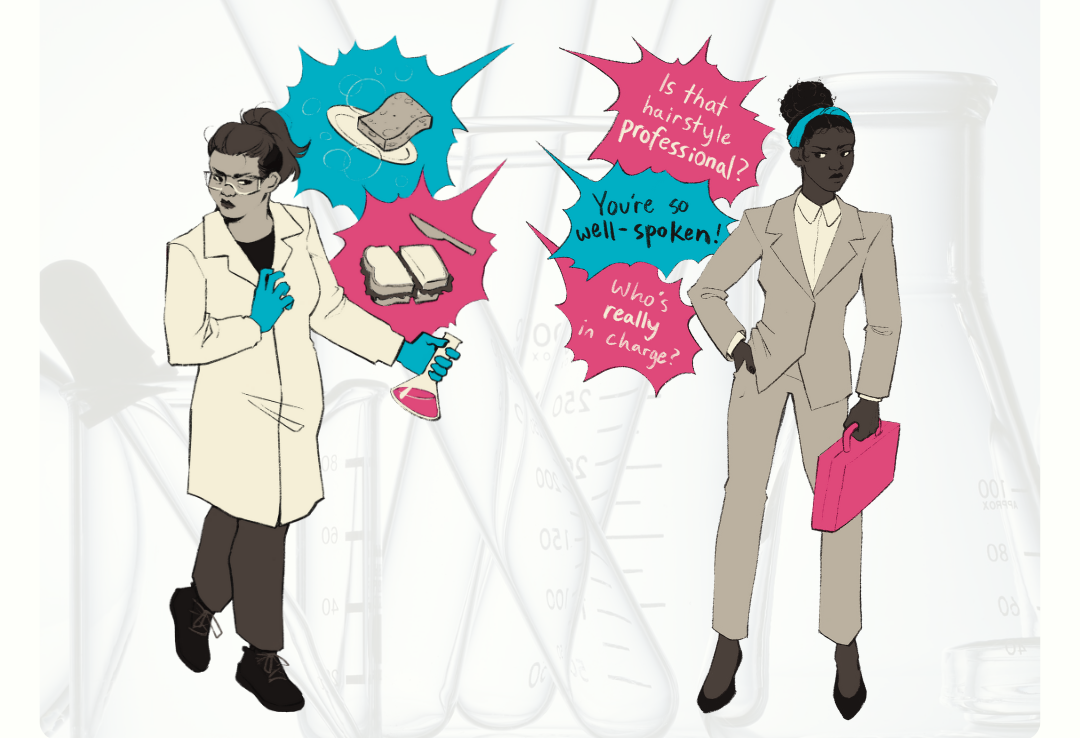

Intersectionality, a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe overlapping systems of oppression, outlines how one’s racial identity intersects with other minority identities such as gender, religion or disability. To describe experiencing double oppression without including race, one should use the term “simultaneity.” This distinction came from an open letter made by several Deaf and DeafBlind individuals in March 2020.

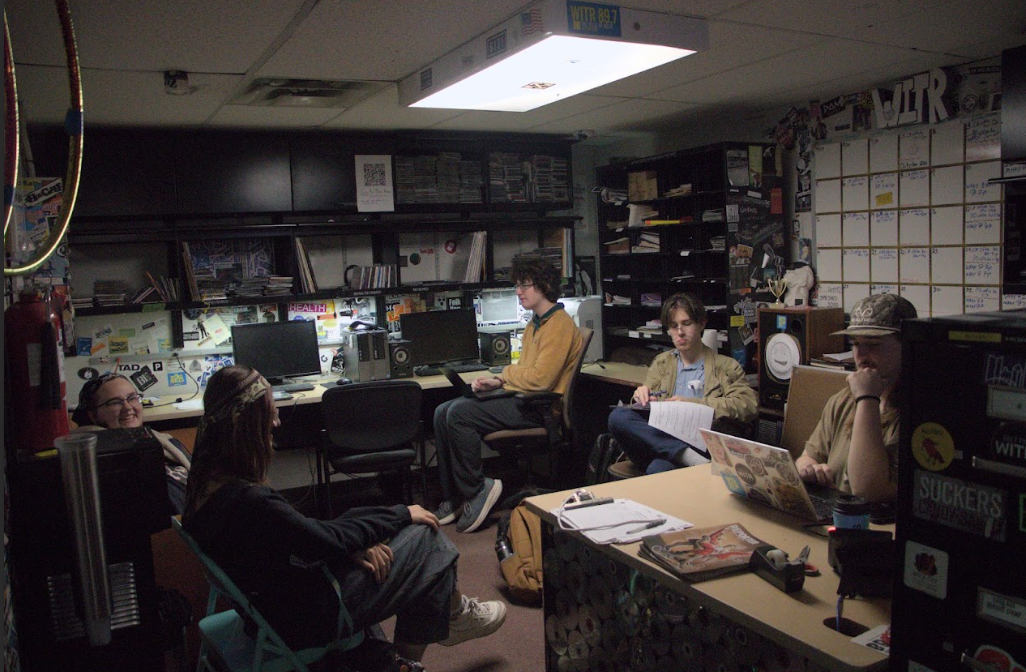

Deaf people uniquely encounter intersectionality, influenced by language choice, hearing ability and varying levels of involvement in the Deaf community. Many Deaf students who come to RIT/NTID come from areas with limited diversity. For them, intersectional deaf clubs — such as the Asian Deaf Club, Latin American Deaf Club and Ebony Club — serve as safe havens in a predominantly white institution. While there are plenty of cultural clubs at RIT, NTID cultural clubs are unique in providing students of color with the opportunity to celebrate their Deaf identities.

Tie Barnes, a second year Computer Engineering student and the president of the Asian Deaf Club, spoke about intersectionality and the importance of cultural clubs.

“Asian culture and Deaf culture both have different expectations. It’s hard to balance both cultures,” Barnes explained. “When I focus on school, the Deaf community wants me to socialize, and when I socialize, my upbringing makes me feel obligated to focus on school.”

Coming from the South, Barnes seldom saw others who shared his racial identity and hearing status. This motivated Barnes to seek out the Asian Deaf Club, where he built connections with others who shared his culture and experiences. Seeing how differently people expressed their shared identity reinforced Barnes’s belief that there is no single way to be Asian, contrary to what may be conveyed in the media.

Closure of Deaf Spaces

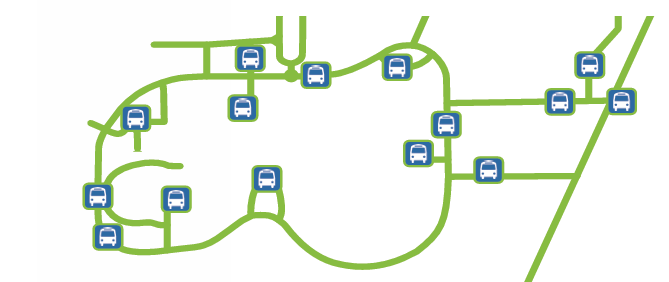

Recently, deaf spaces on campus have been facing challenges. Last semester, The Commons, a beloved space for the Deaf community, was transformed from a dining space to a take-out-only space. On Feb. 3, a town hall meeting was held at SDC to discuss the planned changes to club rooms on the building’s first and second floors. The dedicated club rooms on the first floor will be transformed into multi-club spaces that can be reserved, while the second-floor Club Suite 2.0 offices will be occupied by NTID faculty.

This planned closure is impacting cultural clubs such as the Asian Deaf Club and the Latin American Deaf Club. For generations of students, NTID clubs have occupied the space. “Asian Deaf Club had their room in SDC since 2006 and accumulated 20 years of history,” Barnes shared.“There is a lot of cultural and club documentation being held in our room. Asian Deaf students are losing a space that belongs to them.”

“However, we have to move on. The decision was made by the administration. We have to accept that things will change,” Barnes expressed.

Jesus Alvarado, a third year Biology student and the president of the Latin American Deaf Club, agrees with Barnes, expressing, “At the town hall, we learned that the choices were made by the RIT administration and we understood that it was out of our hands.”

The conversion of club rooms into mixed-use spaces is impacting club operations. Without private space to hold meetings, study sessions and student gatherings, the Asian Deaf Club could lose its ability to foster community outreach. According to NTID administration, the planned closures of the club rooms follow RIT’s broader policy of closing club-specific spaces, such as the Model Railroad Club and Anime Club.

Barnes also expressed his disappointment in the transformation of Commons, a popular hangout spot for many Deaf people to chat and eat.

“Last year, I noticed many Deaf people hanging out at the Dining Commons. Now, there’s just a long line and people getting their food and then leaving,” shared Barnes.

Not only do dining spaces exist as hubs for Deaf students, but cultural clubs also provide Deaf people from different backgrounds a space for shared identities and languages.

Alvarado emphasizes the existence of cultural clubs, stating, “The point of the club is to provide connection. Many Latin students at RIT come from places where they didn’t have the chance to learn or appreciate their culture. We provide that for them.”

Although the upcoming changes could impact club operations, both organizations’ presidents remain optimistic. Banquets, events and cultural celebrations are still anticipated throughout the year. With Deaf student life in flux, progress is possible with continued advocacy and student-centered decisions.