This article is a guest essay by RIT student Adria Clines and was included in the October print edition of Reporter.

“Let’s play swipes!” My friend yells on the dorm room floor. We huddle over a phone screen close enough to smell coconut shampoo and goldfish. Crouching down to crisscross applesauce was a time machine back to middle school slumber parties where everyone shared their crushes in a truth circle. Giddiness would spread through my head like whispers: shaky in my breath, quiet, but so distracting.

In the dorm floor truth circle, giddiness does not get as swept up in the air. We do not talk about crushes; we tally up matches. In place of a conversation is a transaction.

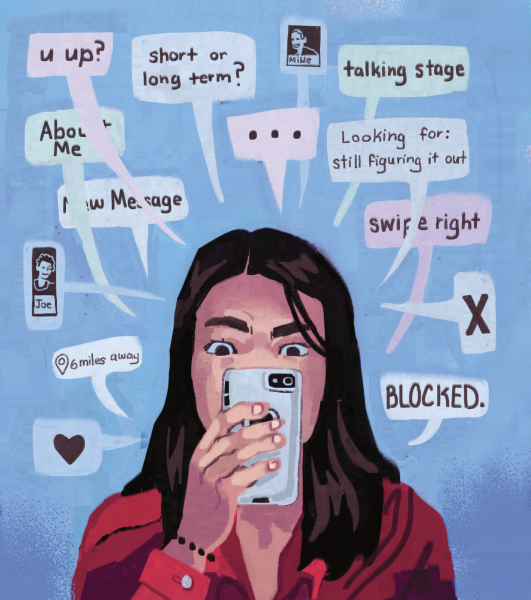

Matching is the objective of popular dating apps today. For young Americans (ages 18-29) the most used apps are Tinder, Bumble and Hinge. In 2012, Tinder launched its signature system of matching short profiles of photos and basic facts by swiping right to like or left to discard; Bumble is similar except females in heterosexual matches must make the first move. Profiles are mostly curated based on proximity and sexual preference. For Hinge, matches are more stimulus-focused along with location, using an algorithm based on interests and personal information to find people close and statistically more compatible.

A popular setting in dating apps is a “relationship type” range on a scale of commitment. One of my friends sets her label to “short-term” and in that moment the swipes feel weightless to me. I had never imagined a relationship without internal or external pressure to expect something more. Casual relationships have existed throughout history, but I always thought they would clash with my set of values or tendency for attachment. In the internet’s truth circle though, the idea of a hookup with a stranger suddenly seemed more reasonable than simply asking out a crush.

Many adults I knew met their partners in college and I had always thought of myself as a romantic – had the times changed? Was it the lack of accountability behind a screen, or the euphoria of instant gratification that amplified the risk of in-person rejection? I discovered a newfound freedom…and anxiety.

In modern romance more than ever, I can question my own identity but have never felt so unable to answer my own questions. I wonder if we are confusing self-obsession for self-discovery as the endless possibilities of catching someone’s eye or changing one’s mind have become more than just a celebrated hobby but a false authority. A social stamp of approval to tether oneself in something that is fleeting. Teenage confusion is stereotypical, but are the effects of gamified dating on Generation Z impacting people’s psychology uniquely? With record high app usage, I ask if this is liberating the youth to explore what they like, or tainting their view on organic connection and their identities altogether.

Human biology is not perfectly explained with our primal wills for survival translating to commitment. Being love-struck, or having initial infatuation, releases different hormones than engaging in behaviors of long-term, monogamous relationships. Harvard Medical School professors, Richard Schwartz and Jacqueline Olds, explain the initial phases of love increase cortisol and deplete serotonin which causes “maddeningly preoccupying thoughts.” It also produces high levels of dopamine “to make love a pleasurable experience similar to the euphoria associated with use of cocaine or alcohol.”

Being love-struck is first cued by attraction. Different combinations of factors affect people differently but in general, physical appearance controls much of attraction because it also gives the persuasion of confidence and intelligence. Current dating apps are very visual-based; the top of each profile starts with a set of photos chosen by the user. This means people have the option of love-struck attraction many times a day while playing swipes.

Harnessing the pleasure of our biological responses sounds helpful when I consider some of the tolls college students face. When there are essays, exams and events to bounce between every week, a moment of pause for my critical thinking sounds healing. The blunt chemical joy also distracts from the possibility of awkwardness or navigating the guilt of breaking off a connection I might not end up wanting. When my friends discuss their new matches though, sometimes I can see dependence from the outside and maybe this bliss is some hypnotic call we cannot break the beat of.

The psychology of long-term love is not as rapid or bold. Dopamine makes life pretty but does not account for all its beauty. I think of organic connection from this lens of traditional love stories – the plots, images and values built in our literature and cult classic films.

Even young heartbreak, or teenage angst can give perspective. Today, in the complicated scene of gamified media, there is still merit in reflection. Underneath the compulsive counting of Snapchat streaks or programmed jealousy of read receipts, we can still grow our emotional capacities after experiencing pain.

For me, it was a rite of passage to understand how deeply I could love. In high school I adored one of my best friends like a partner, but I did not realize it until it was over. Two weeks until he moved away, I stressed every day to make plans to ensure he would not forget me. When I laid on my floor and my mother told me, “One day all the worrying would pass” I prayed it never would because it meant I would not know the boy I loved anymore. Dreading the day his contact wasn’t in my notifications was more comforting than the eerie disassociation of swiping down and truly seeing it empty. Yes, I was gripped in the vices of my phone, but it was an accessory wound to the sore, but valuable, growing pains.

This is what complicates romance in Generation Z: what do we decipher value from? Dopamine of infatuation? Security of faithful love? Promises in progressive ideals? There is duality in our age of technology where we have access to a bank of knowledge before us: a guide for our health and human nature, but also an invitation into change: more efficiency and an open mind. I have grown up in a time where defying common knowledge has been normal. In middle school, we would gasp if our peers were rumored to have hooked up, but we would also take the Rice Purity Test and secretly hope for the lowest score. In high school, I respected virginity as sacred, but I also respected its definition as a social construct. Somewhere ingrained in my generation is this understanding that sex is historically shameful, but it could also be inspiring. Maybe we are giving up too fast on inherited ideals; maybe we are just swapping them out for more ideologies. It is hard to say if tradition and evolution can coexist.

Before dating apps were the preferred way to meet people, the main channel was through mutual friends which allowed for community vetting. Although imperfect, it still gives some physical clues. Dating apps are usually less concrete. We have the option to catfish others, but also ourselves. I know I have the capacity to love deeply; I knew this when I learned to accept my parents’ divorce as a change, not tragedy. It is challenging to think of boiling myself down to a simple profile, then commenting on other people’s boiled-down lives and still being able to look at myself as deeply loving. The shelter of the app starts to feel less like trusses of code and more like my own bones.

In psychology, there’s a term called “learned helplessness”, a team of researchers discovered it in 1967. A group of dogs were subjected to electric shocks they could not escape because the wall they needed to jump over was too high. For the next round, the wall was shortened but they did not even try because they were trained they could not. I sometimes feel that dating apps turn us into dogs. Image after image, like shocks that say: “you are shallow” – we decide if we can love someone before knowing their name. Our “type” is buzzed at our faces like a punishment. When meeting someone who then initiates a deeper conversation, it is uncertain if we are capable of this love.

This leads back to the gray area of modern love: options are created to stimulate us, then leave us ironically neutral – liking ourselves, disliking ourselves. When we are taught to trust people differently online and in person, then to look at ourselves differently online and in person, we are offered a wormhole between two worlds that has not yet existed before. Ambiguity has terminology now, from a “situationship” to a “talking stage.” In some ways, I wonder not how dating app romance has defined my culture’s identity, but how our identity has defined romance.

Phone addictions define us. Dopamine band-aids for emotional unavailability define us. Hookups, ghosting and thirst traps define us. The obsession, social ritual, fallback, confidence booster called dating apps define us.

But, really, our open mind for all this complicated future is what defines Generation Z’s love.

One time in middle school, I sat on the floor of my great grandparents’ stucco home. My aunts gathered with me around a photo album. There was one of two teenagers, legs dangling over a concrete wall, smiling. It was black and white, but it looked like sunshine and bubblegum: my great grandparents as newlyweds. He proposed to her in a letter and she took the train all the way from San Francisco to Manitoba. It did not make me anxious. Below their Holy Mary statue, I prayed for a love like that.

On the dorm floor alone, I wonder when my heart will long for this again and I am okay with that.